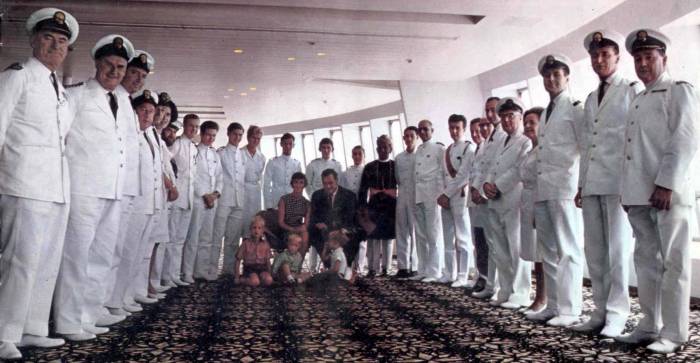

The Purser's department, ss Iberia 1963. Photo: Diana Borcherds (nee French)

.jpg)

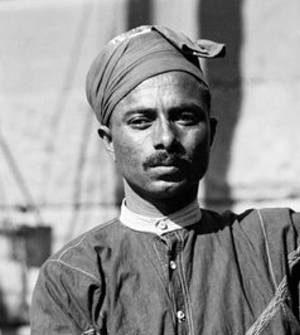

Kalasi securing the port gangway, ss Arcadia. Photo: Michael Ian Byard

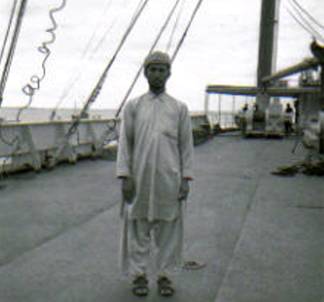

First Class Seaman reporting for duty - ss Surat 1968

Forecastle stations: Second Officer, 6 Kalasis, Serang, Bosun and Carpenter on the windlass.

P&O first positioned a ship east of Suez in 1842 and established a base in Calcutta. From there a service was started to take passengers and freight to Suez, and then overland to Alexandria and on to UK. The ship’s British Officers and Crew were required to be relieved every two years and it was quickly realised that although the cost of sending out Officers from UK could not be avoided, it made sense to replace the outgoing British ratings with locally engaged, far less expensive, Indian crews. Various manning arrangements were tried, but it was not until after 1853 when a P&O office was established in Bombay, that a manning structure emerged which was to remain in place for more than a hundred years.

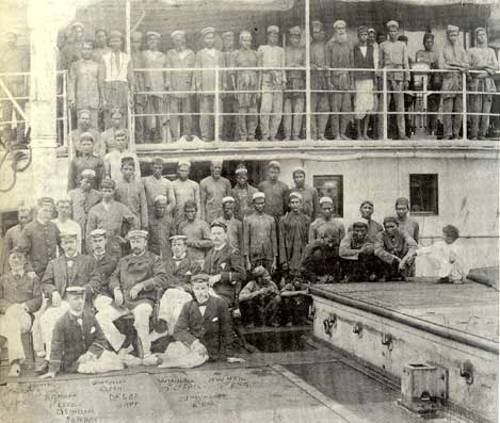

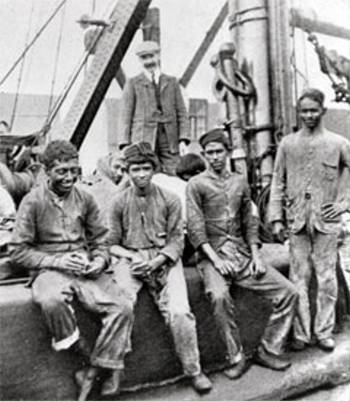

Asian Crew and European Officers of a late nineteenth century P&O vessel. Memorial University Maritime History Archive [MHA]

Lascar crew members, ss Ballarat, 1890. Image reproduced by courtesy of State Library of South Australia.

Lascars, splicing and seizing mooring ropes, Royal Albert Docks, London 1950s

Note: The term “Lascar” is not in use today, but as a period term it identified men who were engaged at ports in India under the special terms of a running Agreement. The Lascar Agreement replaced the standard British Board of Trade foreign-going Agreement for seafarers of Indian, African and Middle-Eastern origin. The Indian “Lascar Act” of 1832 was repealed only in 1963, having outlasted the time that Lascar was used as a term in British labour legislation. In 1940, in the period of decolonization, Labour minister Ernest Bevin protested the term with passion and “would not allow them to be called Lascars any more. They are Indian seamen, and when you get rid of the term Lascar, you will rid of the conception that they are cheap human fodder.” It was 1953, however, before sensitivities to the differentiation of “Indian seamen” by race prevailed and they became “Seaman Class I and Class II”. Today India is second only to the Philippines in the numbers of seafarers it supplies to the world’s merchant shipping. A trade union organization, the International Transport Workers’ Federation, is perhaps the most effective institution operating globally in an industry which still exploits racial difference.

Deck and Engine Room Ratings

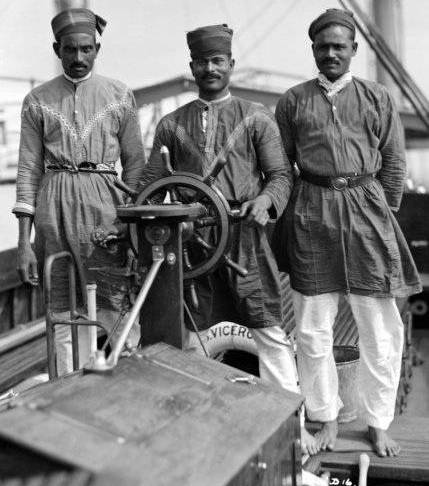

Serang and Khallasis ss Viceroy Of India, 1929

The Deck Ratings were Hindu or Moslem and were recruited from the various fishing communities in India. They were always referred to as the Khallasis, a colloquial term which is still used in India today to describe unskilled labour.The Engine Ratings were Pathan Hill Farmers from the north of what is today Pakistan, mainly from Swat. This is an immense distance from Bombay and quite why they were first employed is not known, but it is assumed that it was because of their physical toughness and ability to work in the harsh environment of the Engine Room. They were colloquially referred to as the Agwallahs, or Firemen.

ss Himalaya's Deck Department Serang - 1968

Both the Deck and Engine Crews were headed by a Serang, who was charged with recruiting his own crew usually from his own village, and at the end of his time on board he received a bonus depending on how many of his crew had not deserted in the interim. This arrangement only came to an end in 1958.

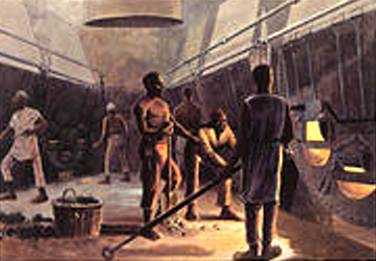

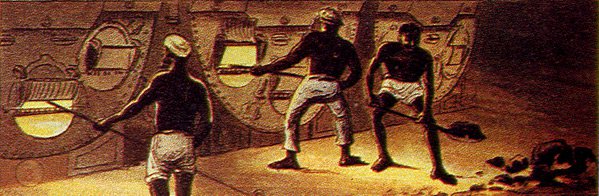

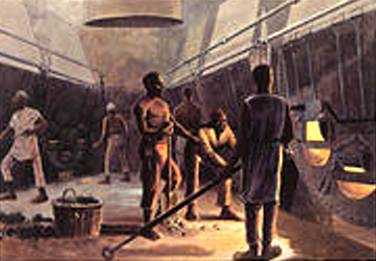

The Boiler Room & Stokehold , c1890

Painting the ship's side ss Himalaya 1968

The last traditional Indian Deck and Pakistani Engine Crews were discharged from Canberra in 1986, when they were replaced by a Pakistani General Purpose Crew. Today, the P&O Cruise Ships still have Pakistani Crew, who are the descendents of the Agwallahs, but are employed as Deck Seamen.

Catering Ratings

For the Catering Ratings they looked to the Portuguese Colony of Goa to the South of Bombay because they realised that they needed to employ Christians who did not have the Hindu dislike of handling beef or the Moslem objection to handling pork and dealing with garbage. Goa is 30% Roman Catholic and 60% Hindu. In a few instances the Roman Catholic crew members came from families where there had been inter-marriage with Portuguese, but most were from local families who had converted to Catholicism and then adopted Portuguese names. This was common practice in all of the Portuguese colonies. The most common surname was, and still is, “Fernandes”, and there also many who have the first names of “Francis Xavier”, after the patron saint of Goa. Most came from the district of Salcette in the south of Goa but there is also a village called Santo Estevao further north near the state capital of Panjim (now Panaji) where there is a long tradition of P&O employment.

ss Canberra - first class restaurant staff 1963

For over a hundred years, these ratings were always referred to in P&O as “Goans”, a word probably derived from the word “Portuguese”, but since the 1970’s this has no longer been acceptable and if used can cause offence. The correct term, today,is “Goan”. The most senior Goan Rating on board passenger ships was the Chief Pantryman, and he was always involved if there were any disciplinary or welfare issues. The last holder of this position was in Canberra in 1986 when the on board Hotel was re-organised, many of the old job titles updated and an Accommodation Supervisor became the Senior Rating.

Today, large numbers are still employed in the P&O Cruise ships but are referred to as “Indian Crew” because modern employment legislation in India requires that they be recruited from all over the country. Nevertheless, more than 80% are 1953and many are the sons and grandsons of those employed by P&O since the mid 19th Century."

By Derek Warmington

In its long and eventful history, the P & 0 Company has been faithfully served by many devoted servants. Not least among them should be numbered the countless thousands comprising Asian crews, past and present. Generations of them have come from their humble homes, all over the sub-continent, each to devote the best part of a lifetime to serve in the Company's ships. In the P & 0, as in many other shipping lines, they became an institution.

Viceroy of India ~ Lascar Crew manning a ship's launch.

Crews from all over the Indian sub-continent were found in all three departments, with Moslems on deck and in the engine room and in 1953, Roman Catholic Goans in the Purser's department. Kalasis, or Seamen, came mainly from the Portuguese colony of Daman and adjacent areas in Gujarat, from parts of Kathiawar, the Ratnagiri district and other places in the Konkan, from Cochin and the Malabar coast generally. Indians from the above areas signed Articles in Bombay and were always known as "Bombay crews". There were also "Calcutta crews", hailing from the other side of India, but the P & 0 only employed them in ships running to that port.

Painting ss Arcadia's funnel 1964

The term Lascar is believed to derive from the Persian lashkar, meaning an army, a camp or a band of followers. The first European use of the word dates back to the Portuguese employment of Asian seamen in the early 1500s. Lascars were both recruited to serve on European ships and paid through a Ghat Sarhang, an Indian agent. This term comes from the Hindi word ghat, meaning landing place, set of bathing steps, and mountain pass, and the Persian word sarhang, meaning commander or overseer.

Boiler Room - The Illustrated London News., 1906

The engine room Agwalas, or Firemen, were mainly Punjabi Moslems or Pathans, from Pakistan and the disputed areas of Kashmir. They were found in Bombay ships, while the Agwalas on board Calcutta ships came from the hinterland of Chittagong, in what was once Eastern Pakistan, now called Bangladesh.

The great majority of stewards were Goan, from the Portuguese colony of Goa. The majority were descendants of the early Portuguese adventurers to the East. They all had Portuguese names and were devout Roman Catholics. A large number of them spoke good English and made excellent stewards and cooks. Many were fine musicians too.

The Deck Department

The noble Lascar: a loyal, hard-working Company man

In charge of the Deck Department's Kalasis was the Serang, the senior Indian petty officer or Bosun. Reporting to the Chief Officer, his powers were extensive: keeping the deck crew in order, directing them at their work, and administering discipline. As Moslems, and non-drinkers, they were generally much easier to handle than European sailors.

Strathmore's Serang - 1963

A good Serang was worth his weight in gold to the Chief Officer. Normally, the Serang was assisted by one or two Tindals, Bosun's Mates, and under them, four Kalasis, with special responsibilities: the Cassab, the Bhandary, the Paniwallah, and the Topass. The Cassab was in charge of the deck stores: coils of rope, drums of paint, blocks and shackles of all sizes, many different kinds of gear were in his charge from the Cassab's Store. The Bhandary was the crew's cook, devoting his time to the preparing of curry and rice for the Kalasis. The Paniwallah, or Waterman, was the Carpenter's mate and, as his name implies. he tended the hoses when watering ship. The Topass performed more menial tasks for the crew, and unlike the rest of his department, was normally a Goan. At harbour stations, the Serang would normally be on the forecastle, assisting the Bosun and Second Officer, while one of the Tindals would be aft, with the First Officer. Orders were given in Hindustani, which all P&O deck officers were expected to learn.

Lascar deck crew under the supervision of their officers, 1865

First Tindal ~ ss Viceroy of India 1929

To get the best out of these crews they must be properly led and their serangs, or head men, hold key positions in the ship's organisation. Thus the serang of the Asian deck crew will be responsible to the chief officer for all "sailorising" work - pulley-hauley, deck scrubbing, chipping and painting, maintenance of cargo gear, boat work, etc. He has almost autocratic powers and is responsible for the discipline of his charges.

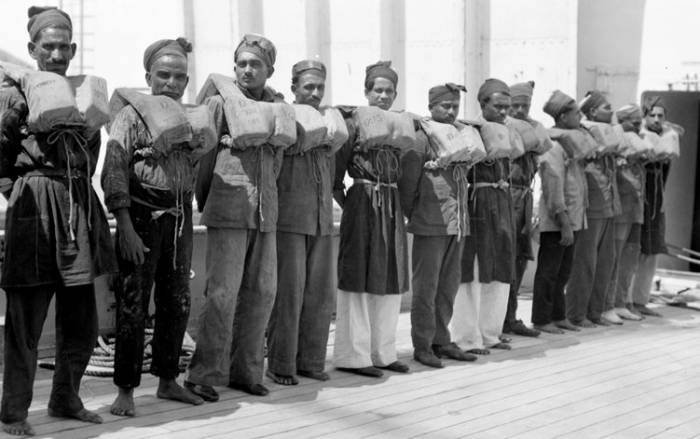

Deck Crew at Boat Stations ~ ss Viceroy Of India 1929

Kalasis wire splicing - SS Ballarat 1961 - Serang seated

It is the Kalasis who heaved on ropes and scrubbed decks, who preserved the ship against the inroads of weather and time by chipping and scraping, painting and varnishing. They overhauled the cargo gear, greasing the blocks and oiling the wheels, keeping everything looking "shipshape and Bristol fashion". On passenger ships, the size of the deck department varied from around fifty Kalasis in the smaller ships to eighty on the largest liners, where there could also be as many as five Tindals and two Cassabs.

Painting the funnel - SS Chusan 1972

ss Strathmore, overhauling derricks, 1959

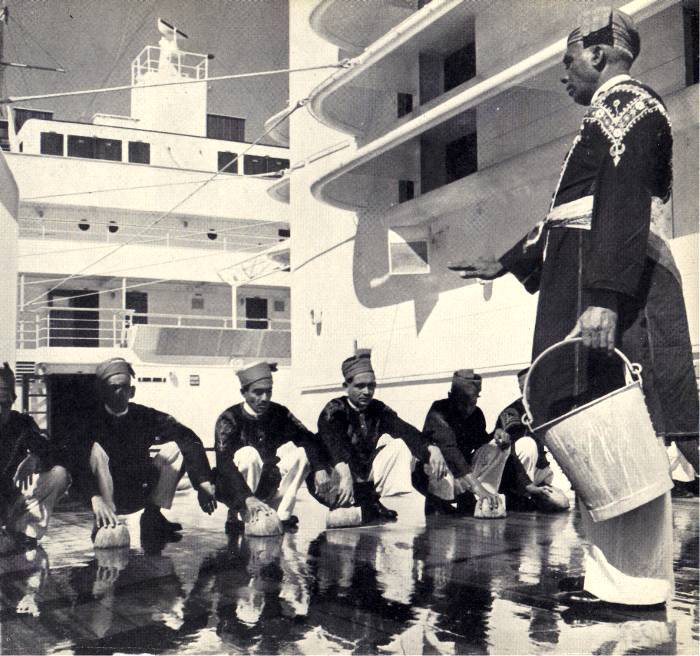

Holystoning the deck ~ ss Himalaya 1968

Electric deck scrubbing, ss Arcadia 1969

The uniform worn by the deck crew consisted of a blue, embroidered, knee length, cotton tunic called a lalchi, a red rhumal or folded kerchief worn around the waist and knotted in front, white pantaloons and a round hat, or topi. The topi was a canvas affair, made without a brim. and painted black. They were often made by the crew themselves. The Serang and Tindals tied a colourful riband of Bengal tartan around their topis, while the Kalasis and Cassab wore plain red ones, and the Paniwallah and Bhandary - none.

SS Strathnaver Deck Crew with Chief Officer 1951

It was P&O tradition, that the Serang and Tindals, as befitting their importance, painted fanciful designs on the tops of their topis. They also had boatswain's calls, whistles, worn on a silver chain around their necks. In the case of the Tindals, they were a badge of authority, while the Serang could use his for piping Harbour Stations or Fire and Boat Stations.

Fire & Emergency drill aboard the ss Strathmore in 1959

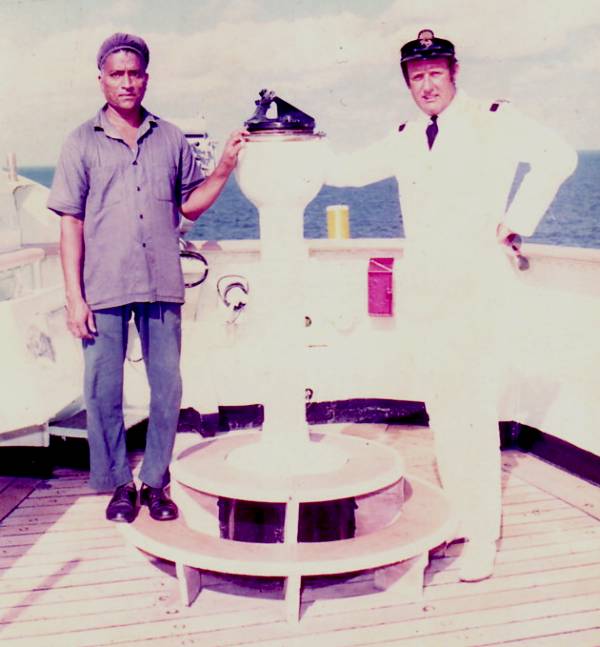

Bridge Wallah and First Officer Nick Messinger, ss Chusan 1972

Possessed of a wonderful sense of humour, he had the ability to conjure up chapatis out of thin air!

Hands aloft, overhauling standing rigging, ss Himalaya, 1970

Sukunni on the wheel - SS Surat 1968

On board the Company's cargo and cargo-passenger ships, Sukunnies, or Quartermasters, served as bridge watchkeepers, taking the wheel, cleaning the bridge brasswork, and acting as messengers or lookouts. In port, they kept watch on the gangway. Unlike the Kalasis, they wore the 'fore and aft' navy blue serge rig of a Royal Naval rating, or blue serge jacket, complete with a round sailor's hat.

Sukunni on the wheel - MV Somali 1965

In hot weather they wore the white variant of this uniform. The Sukunnies were assisted by a Kalassi Bridge-Wallah, who carried out the more menial bridge tasks, such as scrubbing the deck and washing down the paintwork.

Bridge Wallah scrubbing bridge deck mats - SS Surat 1968

'The crew are all Lascars with the exception of the quartermasters, who heave

the lead, and have other responsible duties. The Lascars are a race of sailors,

and take kindly to seafaring ways. They are drawn from the Gulf of Kutch and

from the Indian fishing villages north and south of Bombay, and are trained from

childhood to handle boats under all conditions of wind and weather, and the

whole ship's crew comes as a rule from one village or community, and are all

known to each other.

They are in charge of a serang, or headman, who is responsible for them,

and this system ensures the obedience and good conduct of the men, who are known

and can be traced if they desert or misbehave. Not only would a deserter lose

his accumulated pay, but he would be unable to return to his wife and family

without being caught and punished. The crew sign on for two years, and are

docile and easy to handle. Though it is little known, Lascars bear cold better

than Europeans, provided they are not kept in it too long. This is due to the

amount of caloric absorbed into their systems under their own tropical sun. They

certainly add to the picturesqueness of the steamer, with their red sashes and

turbans, and the quaint adornments that they love.'

A Pattern of Loyalty

The loyalty of Asian crews was tried to the full during the second world war, when they continued to go to sea in British ships as a matter of course, despite the torpedoes and bombs. Many of them died with their European shipmates. When P&O liners were requisitioned for service as armed merchant cruisers, the Asians invariably volunteered to stay with their ships, and some of the engine-room crews served under the White Ensign in this way. Many Asians received awards and decorations for gallantry in the course of the war.

Sir William Currie, chairman of the P. &. 0. Line, once added a revealing anecdote in the course of a speech. He recounted how an Asian deckhand was asked by an American passenger if he were an Indian or a Pakistani. The deckhand looked at the American pityingly. "Me, Sahib?' he replied. "Me, P. & 0."

George F. Kerr in his Business in Great Waters, the war story of the P. & 0. Line, recounts a story of Asian discipline in the face of danger which has some of the flavour of the famous epic of the soldiers aboard the sinking Birkenhead. Bartimeus, the naval author, was taking passage home from the North African landings in the Viceroy of India. When the ship was torpedoed, Bartimeus, stunned by the explosion, groped his way to the boat deck. Not a light was showing and the night was abnormally dark. With arms outstretched, he started along the deck and then stopped as he touched a face. It did not move. Bartimeus spoke. There was no reply.

Puzzled, Bartimeus started off again, only to touch another face which was equally motionless and silent. In a sudden panic, he ignored the regulations and switched on his torch. He found a body of Asian seamen who had fallen in at their boat station under the serang and were now standing to attention awaiting orders!

This story is

amplified by the former purser of the Viceroy, who says that "the men's

silent bravery had to be seen to be believed." He goes on:

"They were undoubtedly frightened as, of course, were many others, but they kept

their heads and looked upon their officers with that trust which the Asiatic has

if he likes and respects his superiors."

The Engine Room Department

The Stokehold - c 1910

Batti Wallah - the Electrical Officer's right-hand man

ss Chusan, Fridge Flat Watchkeeper

Muslim crew at prayers

The Indians and Pakistanis, whether in the deck or engineers' departments, live by their own choice entirely on variations of curry and rice. This is prepared by their personal cook, the bhandary, who will spend much of his time grinding the many spices on a stone. Religion and particularly caste add considerable complications to the ritual of preparing and eating meals.

The Purser's Department

"I have a theory that if you separate the Goan from the sea, he'll wither away. All of our history ebbs and flows with that vast, undulating expanse of blue water. One does not look at the sea with tired eyes but always with hope and anticipation." Selma Carvalho

English Captains developed a liking for Goan cooks, who had no restrictions for handling pork, beef or fish.

There is also evidence of Goan cooks being paid higher wages than their Indian counterparts on P & O and East India

vessels in the eighteenth century. In 1957, Captain Baillie, commanding a P&O liner, wrote:"I have never failed to appreciate

the cleanliness, discipline and comfort of our ships in which the deck hands are Lascars and the stewards mostly Goans."

In a cargo ship the Goan catering crew numbered around twelve, working in either the galley or the pantry. The galley staff comprised the Cook, his Mate, the Butcher, the Baker and the Scullion. The remainder acted as Officer's Servants, serving in the saloon, under the orders of the Chief Steward. In a passenger ship there were about a hundred and fifty Goans, undertaking a host of different tasks alongside their British counterparts.

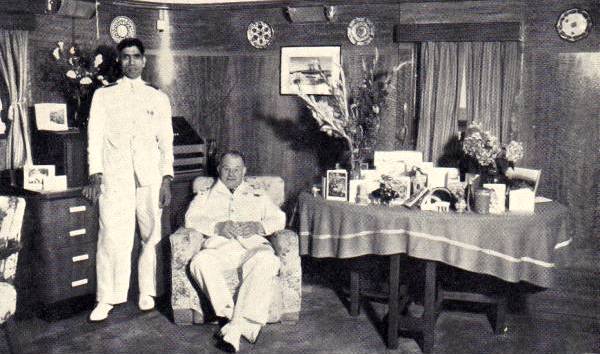

Albert Fernandes, Captain's Servant and Commodore D.G.O. Baillie ~ ss Himalaya 1954

Officer's servants were drawn from the Goan stewards' department and highly regarded by their officers. Morning tea and toast; freshly laundered uniforms with buttons, medal ribbons and rank insignia attached; cabins cleaned and tidy; linen changed and bunks made up; serving the drinks at cocktail parties with a cheerful smile and courteous service were all part of the job.

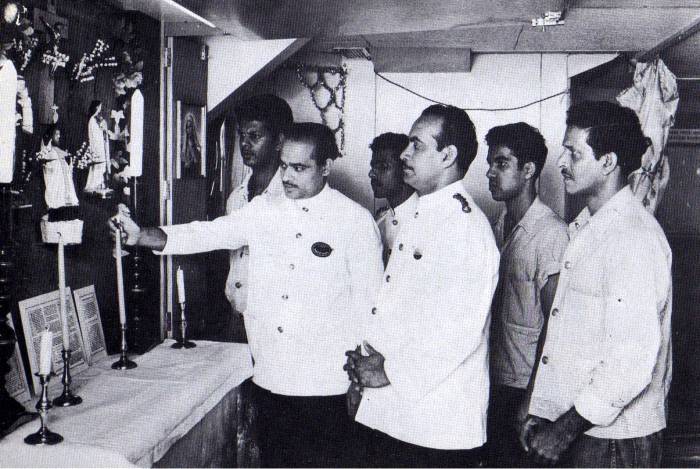

Devout Roman Catholics, Goan Stewards & Cooks lighting their altar candles.

The 1953wore a white jacket with silver P & 0 buttons and blue shoulder cords, with neatly pressed serge trousers. In hot weather they wore white trousers instead of the blue. The Cooks wore the traditional rig of a white coat, blue and white check trousers and a tall chef's hat.

In 1881 the P & O line moved its terminus from Southampton to London. The census reports of that year provide a valuable insight into the changing Goan seafaring population in the port of London. Altogether there were more than 55 1953on four vessels in the port of London - three of these were P&O ships. Many of these men were recruited in Bombay via an agent in Goa. The census of 1901 shows the increase in 1953in London. There were more than 120 Goan seamen in the Port of London, of which 104 were on P&O ships in the Royal Albert Docks.

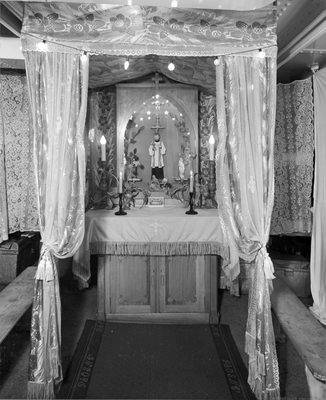

A Goan altar dedicated to St Francis Xavier on board the ss Strathallen

From a series of

prestige advertisements, featuring P&O personalities who served in the Company's

ships,

which appeared in the British national press between August 1955 and February

1958

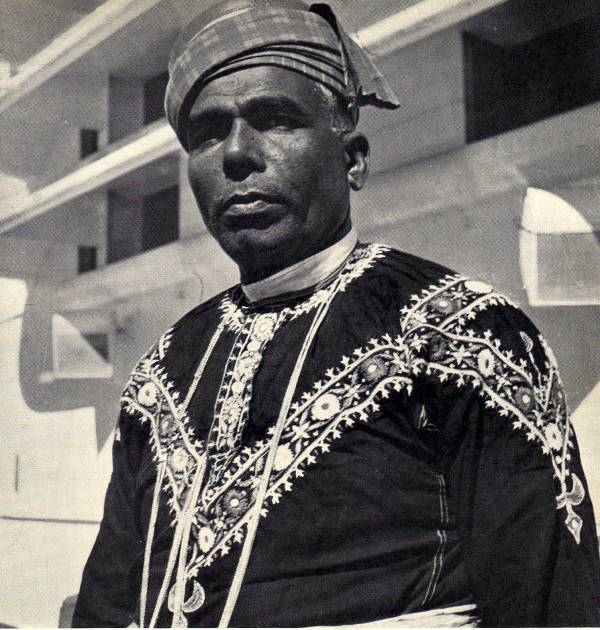

Acoob Cassum, SS Himalaya's Deck Serang

With his keen eyes

he can spot a flaw in a rope --- which might cost a life if left unattended --

and he can splice a wire or rope as easily as you or I might tie a knot. As a

senior deck Serang, a native of Western India, he and his team of Asian seamen

keep the ship spick and span, polishing, painting and scrubbing the decks long

before the passengers rise in the mornings. In a single day he performs a

thousand important tasks - piping the Asian crews to their duties for instance,

or supervising the rigging of the cargo derricks, the mooring of the ship, the

maintenance of deck gear.

The first Asian crews joined the

Company's ships well over 100 years ago, and many of the men serving in the

1970s, were descendents of the original crews. Their ready smile and colourful

uniform were truly a part of the P & O way of life.

Sarfaraz Khan, SS Arcadia's

Chief Engine-Room Serang

Up from Karachi the message travels .... up through the arid plains of Pakistan and the district of Mardan .... on to the village of Zarobi and the house of the Chief Serang ...to the shrewd eyes of Sarfaraz Khan himself. These are the eyes that can spot an atom of dust on an acre of steel floorplates ... wax black with wrath ... grow soft with affection. Now they are bright....for the news is good and there is thinking to be done. The job is a big one. He will choose fifty-six men from the village to go with him. he will choose wisely; the honour of Zarobi and Sarfaraz Khan is at stake. For the next eighteen months his men will work in a bewildering kingdom of pressure gauges, copper tubing and steel. Under his exacting eye, it will gleam like a hospital clinic. Beneath his shrewd gaze there will be harmony. For Sarfaraz Khan is Chief Engine-Room Serang aboard P&O's SS Arcadia ..... a veteran of 36 years experience in the service of the company .... a man with 17 relatives on P & O ships.

Caetano X. Fernandes, Table Steward aboard SS Chusan.

As you approach your table in the

dining saloon, your appetite surges so sharply that you can't help rubbing your

hands in anticipation. Instantly, like some friendly genie of folklore, the

quiet man in the white jacket materializes by your chair. No sooner are you

seated than you find a napkin in your lap and a menu in your hand. You order.

The friendly genie smiles - then almost before you realise that he has left your

side, the melon appears complete with sugar and ginger. Next your fillet of sole

arrives, grilled with a splash of lemon juice. Then comes your chateaubriand

steak, not quite medium, not quite underdone, just the way you like it.

Meanwhile your butter is

replenished, your glass filled, your slightest wish attended to. Never in your

life have you had such service, and the quiet man is delighted. For he is

Caetano X. Fernandes, Table Steward aboard the P & O's SS Chusan, bound for

India and the Far East. One of the 72 Goan waiters on board the ship .... a

devoted genie of the dining room. Caetano tells you he loves his job, for it is

a traditional part of P & O.

ss Canberra, Commodore, Officers and Crew members, with Passengers at their centre - 1968

Our Asian Crews

by M. Watkins-Thomas in About Ourselves copyright P&O (first

published September 1955)

"In its long and eventful history the P & 0 Company has been faithfully served by many devoted servants. Not least among them should be numbered the countless thousands comprising Asian crews, past and present. Generations of them have come from their humble homes, all over the sub-continent, each to devote the best part of a lifetime to serve in the Company's ships. In the P & 0, as in many other shipping lines, they have become an institution. It is my wish to tell you a little more about them, from where they come and how they live. It is an account meant more for the shore staff than for "they that go down to the sea in ships", who are doubtless better acquainted with the ways of their crews.

These crews are found in all three departments, Moslems and Hindus on deck, Moslems in the engineroom and Goans in the Purser's department. Only Moslems are found on deck in the P & 0, though many companies, such as the B.I. and the Mogul Line, employed numbers of Hindus. It is extraordinary how they all come from certain districts. The P & 0 Kalasis, or Seamen, come mainly from the Portuguese colony of Daman and adjacent areas in Gujarat, from parts of Kathiawar, the Ratnagiri district and other places in the Konkan, from Cochin and the Malabar coast generally. Indians from the above areas sign Articles in Bombay and are always known as "Bombay crews". There are also "Calcutta crews", hailing from the other side of India, but the P & 0 only employs them in ships running to that port.

The Bombay crews are usually preferred by P & 0 Officers, though many from Calcutta are good. The best Indian deck crews are considered to be those from the Laccadive and Maldive Islands. They are, however, very few in number and are mostly found in Indian coastal ships. In sailing ship days they formed a large proportion of the crews of those square riggers, with strangely oriental flavoured rigs up and down the Indian coast. The islanders, so I am told, were wont to run up and down the rigging like monkeys, placing the ropes between their big and second toes and showing surprising agility in laying aloft.

The Agwalas, or Firemen, are mainly Punjaubi Moslems or Pathans, and nowadays, of course, come from Pakistan and the disputed areas of Kashmir. They are found in Bombay ships. The Agwalas for Calcutta ships come from the hinterland of Chittagong, in Eastern Pakistan.

The great majority of stewards are Goans, though Indian stewards are found in some shipping companies. Goans, as the name implies, come from the Portuguese colony of Goa, though numbers of them are now settled in Bombay and elsewhere. They are the descendants of the early Portuguese adventurers to the East. They all have Portuguese names and are devout Roman Catholics. A large number of them speak excellent English and they make good servants and cooks.

In charge of the Kalasis is a Serang and his powers are quite extensive. He is responsible to the Chief Officer for keeping them in order, for directing them at their work, and checking evildoers. A good Serang is worth his weight in gold to the Chief Officer. In a cargo ship the Serang is assisted by one or two Tindals and under them are eighteen or more Kalasis and four people who might be termed "specialists". It is the Kalasis who heave on ropes and scrub decks, who preserve the ship against the inroads of weather and time by chipping and scraping, painting and varnishing they overhaul the cargo, the cargo blocks and gear and, in a phrase, keep everything looking "shipshape and Bristol fashion".

The four other characters are the Cassab, the Bhandary, the Paniwallahs, and the Topass. The Cassab is in charge of the deck stores. Coils of rope, many drums of paint, blocks and shackles of all sizes, many different kinds of gear are in his charge. Under the Chief Officer's supervision he has to keep all this lot sorted out and be ready, at any time, to supply any item of equipment required.

The Bhandary is the crew's cook and he devotes his time to the preparing of curry and rice,' to those who indulge in this wonderful dish, indeed a noble task. The Paniwallah, or Waterman, is the Carpenter's mate and, as his name implies. he tends the hoses when watering ship is in progress. The Topass performs the more menial tasks for the crew and he is also the European P.O.'s servant. Unlike the rest of his department, he is a Goans.

On passenger ships the size of this department is greatly increased, varying from about forty-five men on the smaller ships to eighty on the latest class of liner. There are as many as five Tindals and there are always two Cassabs.

The uniform worn by the deck crew consists of a blue, embroidered, knee length, cotton tunic called a lalchi, a red rhumal or folded kerchief worn around the waist and knotted in front, white pantaloons and a topi. The topi is a canvas affair, made without a brim. and painted black. They are often made by the crew themselves. The Serang and Tindals tie a colourful riband of Bengal tartan around it, the Kalasis a plain red one and the Cassab. Paniwallah and Bhandary have no riband. In addition to this distinct ion the Serang and Tindals, as befitting their importance, have a more richly embroidered lalchi, have a tartan instead of a plain rhumal and paint fanciful designs on the tops of their topis. They also have boatswain's pipes worn on a silver chain around their necks. These whistles in the case of the Tindals are really a badge of authority, though the Serang uses his on occasions, such as for piping Harbour Stations or Fire and Boat Stations. Then there is heard a weird whistling noise followed by the appropriate high pitched cry. On cargo ships the fanciful rigouts described above are not normally worn, only the topi and whistle and ordinary blue dungarees.

,p>Before leaving this department mention must be made of the Seacunnies, or Quartermasters, of the cargo ships, four in each ship. They are watchkeepers, and at sea they take the wheel, clean the bridge and act as messengers or lookouts. In port they are on watch at the gangway. They wear the" fore and aft" rig of the naval rating, complete with round sailor hats. In the hot weather they wearthe white variant of this uniform.

The Agwalas are run by their own Serang and Tindals in much the same way as the Kalasis. The Agwalas's work, though, is of course confined to the multifarious tasks found for them in the engine-room. Strictly speaking, only half the engineroom hands are called Agwalas, or Firemen. The other half are the senior and are rated as Paniwallahs, or Watermen. In some companies the latter are called Tehlwallahs, or Oilmen. The Agwalas and Paniwallahs are mainly watchkeepers. This department also has its Cassab and Bhandary. Since their work is confined to the engineroom, their uniform is appropriately a blue boiler suit.

The Goans in a cargo ship are twelve in number and work in either the galley or pantry. In the galley are found the Cook, his Mate, the Butcher, the Baker (no Candlestick maker) and the Scullion. The remainder act as the Officer's Servants, serve in the saloon and are generally under the orders of the Chief Steward. In a passenger ship there are about a hundred and fifty Goans doing a host of different tasks. In some companies' cargo ships an Indian Chief Steward is carried, and he is called a Butler.

The Goans wear a blue and white striped jacket with silver P & 0 buttons and blue serge trousers. In the hot weather they wear white trousers instead of the blue. In the saloon and whenever else it is considered necessary they wear a white jacket of the "No. 10" variety with blue shoulder cords. The Cooks wear the traditional rig of a white coat, blue and white check trousers and a tall chef's hat. In passing, a word must be said of the Chinese. In five of the Company's ships the Carpenter and Winchman are Chinese who are nevertheless domiciled in India. As a rule they make fine craftsmen and useful members of the ship's company.

Now I think a word might be said as to what the crew do when they are off watch or day work. The diet of the Kalasis and Agwalas is exclusively curry and rice. The Kalasis eat their meals in their mess room. They form a circle, sat down on their haunches, in the middle of this compartment and help themselves off large metal trays placed on the deck. The Serang and Tindals join in and of course there are no knives and forks. The food is picked up with the index and middle fingers of the right hand and thrust into the mouth with the aid of the thumb quite a knack is required. The Seacunnies usually eat in the same mess room as the Kalasis. In fine weather they often eat out on deck. The Agwalas of Northern India usually eat at a table in their mess, though cutlery has not yet reached them either. The Goans, who have a somewhat more varied diet. eat in a more westernised manner amidships, either in the galley or pantry.

In fine weather, at a time when the crew are not working, the scene on the poop about the accommodation is typically Eastern. In the air is a strong smell of curry and rice and perhaps a whiff of aagarbatti, the long thin sticks of incense which burn slowly and give off such a pleasant aroma. Some of the crew may be sleeping, but others, Kalasis, Agwalas and Goans, will be chatting on the poop, sat on benches, on the coamings of their cabins or squatting on their haunches on one of the mooring bollards, an extraordinary looking posture. Some smoke cigarettes, but others will be puffing bidis, the Indian idea of a cigarette, looking like a small cigar.

,p>The Agwalas sometimes smoke hookahs, or hubble-bubbles as they are sometimes known. These can be described as large watercooled pipes, often made of an empty bottle, a cork, an old tin and a piece of bamboo. However, good hookahs can be bought in India for only about eight rupees and these can sometimes be seen on board ship. They are very elegant and quite hygienic. Recently a shop in Melbourne bought fifty of these weird contrivances and they "sold like hot cakes". There are always people willing to try something new.

If the crew are not working they wear pyjama trousers under a long shirt, a singlet and white shorts or any other rigout that they happen to fancy. The Bhandary's Mate might be observed grinding spices on a stone for the morrow's curry. In port some of the men will almost certainly be seen fishing with lines or a cone-shaped bag something like a sea anchor. Others will be doing their dhobi, or washing, by pounding it on the bathroom deck or mending their clothes in their cabins, and most crews bring a sewing machine with them.

Strangely, some of the Agwalas, and perhaps Kalasis, will be seen with red hair and heards. A lot of people think it means that the owner has been on a pilgrimage to Mecca, but this is not always correct, and in some cases the object is merely to disguise the fact that they are going grey and that they are becoming ancient. Some Kalasis might be observed wearing silver amulets around their necks worn from a length of cord, or silver bracelets worn high up on the right arm. The amulets contain a text from the Koran and their purpose is to bring good luck to the wearer. They are given to Moslems when they are still children and a mullah is called in to bless them. The mullahs, the Moslem priests, receive something for their trouble and the boy has the privilege of wearing these tokens of good luck. The bracelets, which are called behdis, are not rings, but the ends overlap. As the boy grows up so the bracelet is expanded from time to time. The amulet is called a dauvis.

The Moslems frequently read their Koran or Hindustani magazines. They may be seen regularly at prayers in approved Mohammedan fashion. The language spoken down aft is often Hindustani. but also to be heard are Gujarati, Malayalam, Pushtu, Bengali and others as the case might be. The Goans speak Hindustani with the Moslems or their own form of Portuguese among themselves. A lot of the men can speak some English, so that you can have quite a babel of voices.

If, as in some companies, the deck crew are Hindus, like can become complicated by the rules of caste. They are often very fussy, especially about food, for religious reasons. One of the best known of their unusual ideas is that if the shadow of a person, who is not a Hindu of their caste, crosses their food, it is defiled and has to be thrown over the side. Moslems have no such scruples, though, like us, they have their superstitions. For instance, when a Moslem is eating he should never have shoes placed. somewhere above his head nor should he ever stand above a version of the Koran. A Moslem. when he is ashore, if he is going to the bazaar to buy fish. should always give alms to a beggar on his way thither in order to have good luck., Three times in a year the Moslems have special religious festivals: they celebrate these and each time they are allowed a day's holiday in the ship.

Asians make useful and accomplished seamen they are respectful, obedient and, if well led, they can keep the ship in an excellent condition. There are occasions, however, when a European crowd would be appreciated. In the course of my career I have served with both Asians and Europeans and, from the point of view of a ship's officer, I must say that I prefer to sail with Asian crews.

Since I am not a walking encyclopedia on Asian crews, it is possible that in this account I might have erred occasionally. For such mistakes I apologise and I will be glad to receive correspondence on the matter. I trust, however, that this account of our crews may prove to be of some interest to readers of "About Ourselves", both ashore and afloat."

'Then, just as we were thinking of repose, the watchmen of the schooner would hail a splash of paddles away in the starlit gloom of the bay; a voice would respond in cautious tones, and our Serang, putting his head down the open skylight, would inform us without surprise, "That Rajah, he coming. He here now."

From 'Tales of Unrest' by Joseph Conrad 1898