"Complaints have been made that for some reason there seems to have been a sort of antagonistic feeling between the engineers and (deck) officers which has been very hurtful to the Company's interests...If such ideas exist, they must be at once abandoned. It is most important that perfect confidence should exist between the engine and deck departments."

P&O Regulations c1860

The Gathering ~ P&O Engineer Officers meeting aboard the ss Simla in 1866. Andrew Lamb, the Company's Engineer Superintendent is wearing the white top hat in the centre of the front row. Photo source: The P&O Collection

Mr Enos Boyes, boilermaker P&O ss China 1881, ss Sumatra 1882. Drowned at Singapore 3rd May 1882

"It has to be said that there was always a divide between the officers on the bridge and those in the engine room. This was not peculiar to the P & O; it was common to all ships on the high seas, merchant or naval, British, American or German, and no doubt other nationalities. In the early days when engineers were considered interlopers the coolness between departments was natural; it was perpetuated by differences in background, education and entry, and by the different nature of the jobs each did. Individuals bridged the gap, but in general, as all who have been to sea know well, oil and water did not mix. In the memoirs of Captain Armitage are anecdotes of Captains and deck officers, innumerable stories of the great who travelled by P & O - indeed they read like a 'Who's Who' of the eastern Empire - but there is no mention of a single engineer. Captain Steele recalled 'by the laws of liner etiquette I was not permitted to fraternize with the engineers or wireless operators'. Liner life was a microcosm of English life."

Peter Padfield, Beneath The House Flag of The P&O

The Chief Engineer

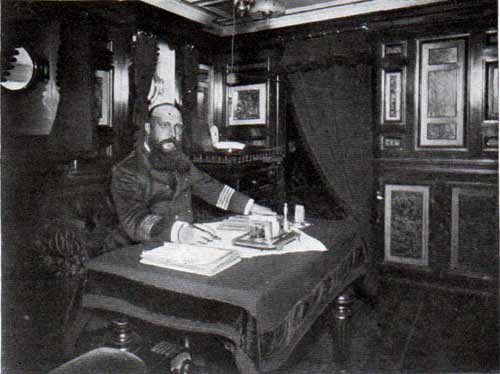

"It is not sufficient that the Chief Engineer should be a good mechanic (although that is a most important and in fact indispensible qualification) but it is also necessary that he should be an intelligent, careful man possessing discretion and judgement for judicious action in time of difficulty and danger, energy and zeal to carry out the work promptly, and method for proper and efficient organization, arrangement and ordering of his department. P&O Instructions for Chief Engineers, 1867.

Chief Engineer ~ ss Maloja 1923

"The Chief Engineer is responsible to the Commander for the efficiency of all the staff and machinery which falls under the care of his department. He is to make such personal inspections of all the machinery under his charge as are necessary to satisfy himself that all is in order, and he will be found more often in the Engine Room than in his office.The Chief Engineer must keep in close touch with the Commander and must consult with him frequently on the number of revolutions to be maintained from time to time in order to achieve maximum economy of fuel from the main propelling machinery. He must also keep the Commander promptly and fully advised of any occurrence in the Engine Room which might affect the navigation or the essential services in the ship. Within his competence there lies an enormous field for economy—that is for expending his resources on useful work only. Fuel consumption, repairs and maintenance of main and auxiliary machinery are the principal factors which he must always keep under the closest control, remembering that labour as well as material is easily wasted."

From: P&O Regulations, Instructions & Advice

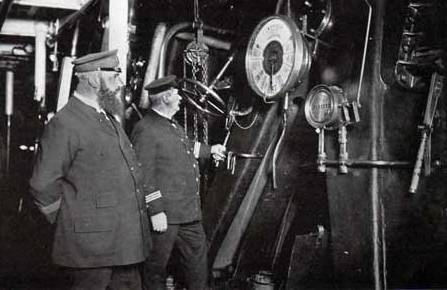

Chief Engineer & Commander, ss Corfu 1957

"In a passenger ship the Chief Engineer is responsible for most of the auxiliary machinery on which passengers largely depend for their comfort, and he is, therefore, to give the fullest service through his department to all reasonable demands made by the Purser's Department. In such matters as the temperature of the water for the dish-washing machines ; the efficiency of the fans and the ventilation system ; the running of the air-conditioning plant ; the temperature at which air-conditioned rooms are maintained ; the maintenance of refrigerators and galley machinery ; the efficiency of the service given by the Purser's Department to passengers must depend largely on the helpful co-operation of the Chief Engineer and his staff, who must all realise that in a passenger ship the convenience of passengers must come first.

The Chief Engineer is responsible for the cleanliness of his crew's quarters and for the discipline of all his staff."

From: P&O Regulations, Instructions & Advice to Officers of The Company

The merchant ship engineer traditionally went to sea to some extent pre-qualified by mechanical engineering experience ashore, and as a result did not get afloat until at least in his early twenties.

The cause may be traced back to the early decades of the nineteenth century when the first steam engines were being installed in ships, and, as is often the case with new technology, the engine manufacturer supplied the first ship’s engineers from amongst his experienced mechanics who had worked on the building of the engine.

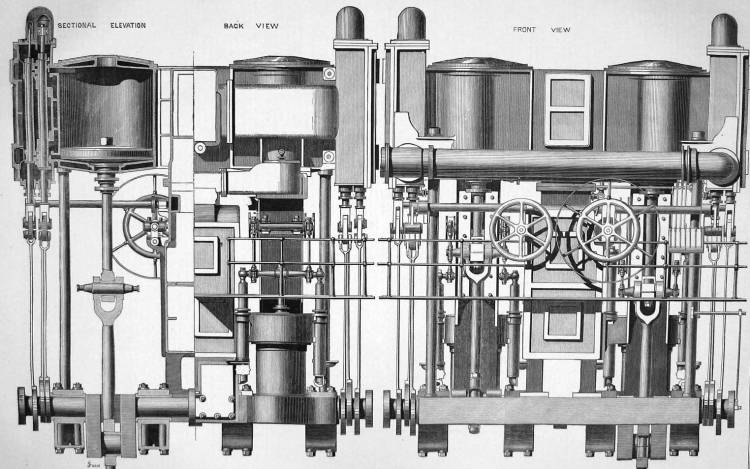

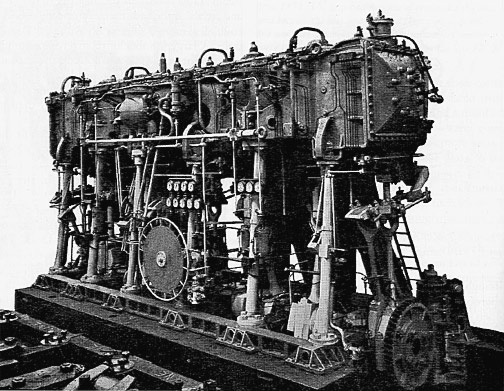

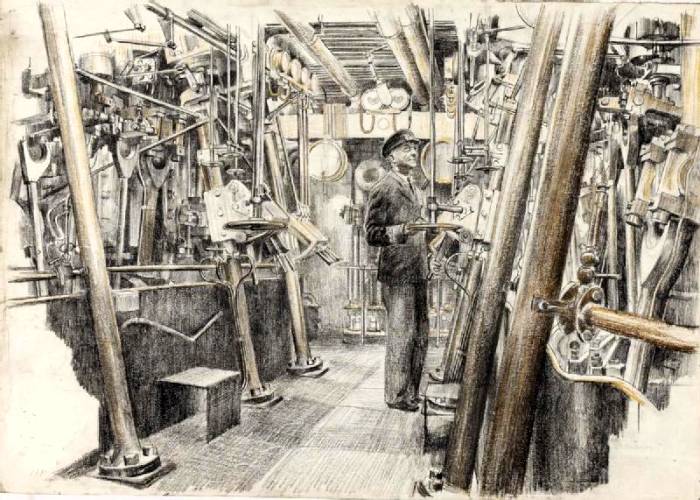

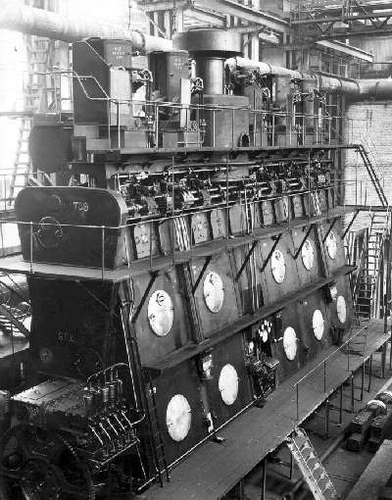

ss Australia's two-cylinder 2626 iHP Blair Compound Engine of 1869

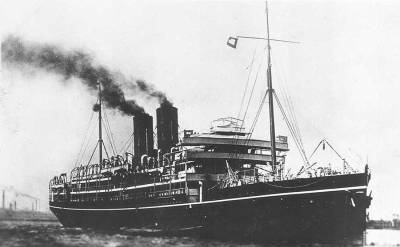

ss Australia, built by Caird & Company Greenock, Yard #153

Engine breakdown at sea was common well into the twentieth century and ship’s engineers had to be skilled in dismantling their engines, making new parts, and, where necessary, rebuilding. The prevention of failure through sensitivity to impending failure and the adherence to regular cycles of maintenance, demanded the kind of experience developed through mechanical engineering apprenticeships, typically of about five years, in heavy engineering workshops ashore, such as those in shipyards and marine engine works.

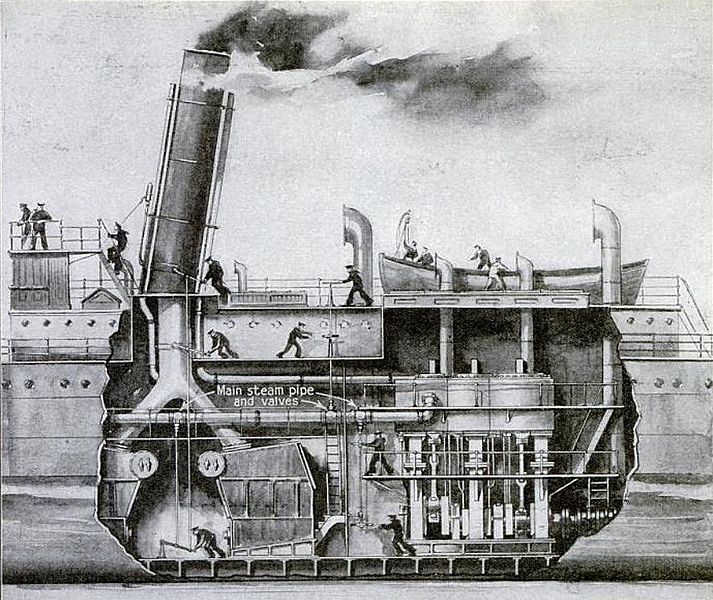

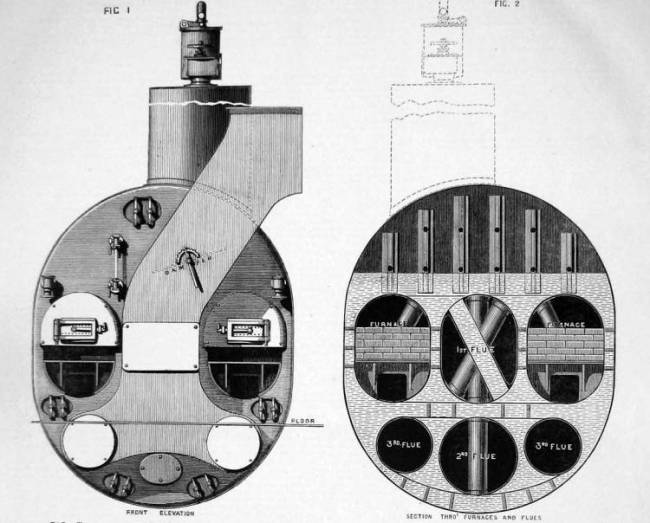

A Collins Engine of 1869 and typical engine room layout.

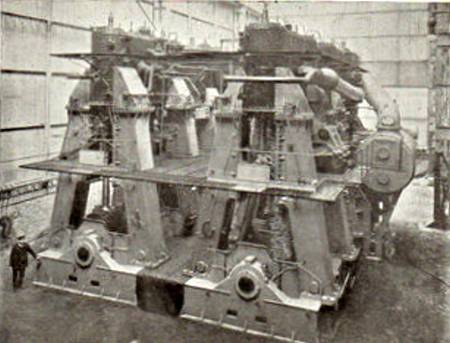

ss Morea's engines, built by Barclay Curle in 1908, Yard # 471. Two, quadruple expansion steam engines. Cylinders 30.5 inch, 44 inch, 61 inch and 87 inch.

Stroke 54 inch, 13,000 IHP, 1,842 NHP. Steam pressure 215lbs, giving 16.0 knots.

ss Morea, 1908

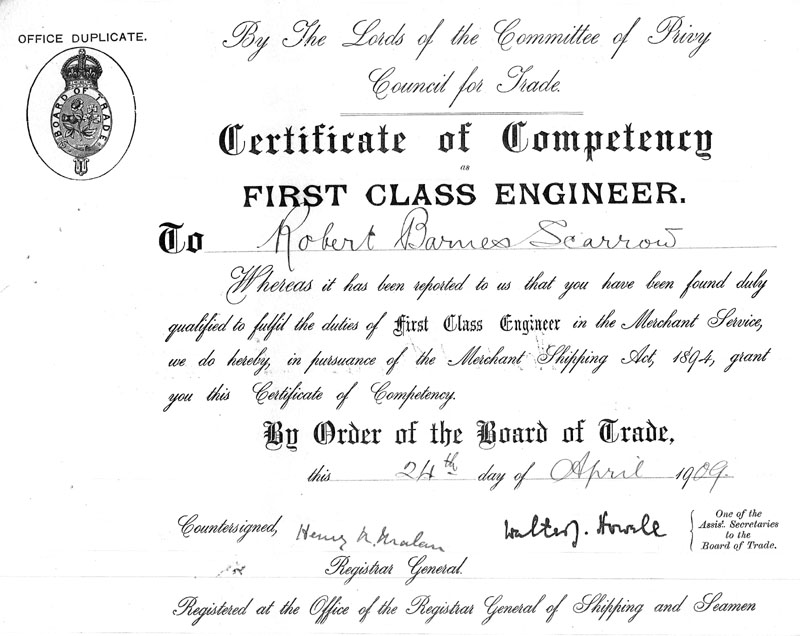

In time, work as a ship’s engineer emerged as special area of mechanical engineering employment based on the apprenticeship ashore, and this requirement was enshrined in the certificate of competency regulations following the passage of the Merchant Shipping Act Amendment Act, 1862. This required foreign-going ships and all passenger ships to carry engineers holding certificates of competency as second and first class engineers, the process, as with deck officers, being handled by the Board of Trade's Marine Department.

A 1869 Hawthorn Patent Multi-flue Ship's Boiler

Again these were national vocational qualifications, but unlike the deck certificates, they attested to experience and skill which could be applied in mechanical engineering ashore as well as at sea. There is ephemeral evidence that engineers went to sea just to obtain the certificate so they could apply for positions in charge of engineering plant ashore, which might otherwise have been outside their reach. Wastage of engineers from employment at sea and shortages of ship’s engineers, seem to have been endemic in power-driven merchant shipping except perhaps in times of depression. Nevertheless, certificates of competency gave engineers equivalent status with mates and masters from whom they had usurped responsibility for ship propulsion.

By the end of the nineteenth century, engineers in the largest ships were responsible for what was in effect the whole engineering plant of a small town, and the more able were beginning to take up seafaring already qualified to some extent in mechanical engineering subjects offered in evening classes at the emergent technical colleges. Men who had completed their apprenticeship ashore could be offered appointments as junior engineers in ships, and after a year (later increased) in charge of a watch at sea, they could attempt the certificate of competency examinations. The majority of ships’ engineers attended a marine engineering school for a few weeks to prepare for the second class engineer examination, and if successful, they could often secure positions as second engineer on the strength of the certificate. Many of these schools were private establishments, but again these had died out by the 1960s, and the certificate courses were being offered in technical colleges.

After a further period at sea, engineers returned to their chosen marine engineering school to prepare for the first class engineer examination. Armed with that certificate, a position as chief or first engineer might soon be obtained, though in the better paid liners of the P&O, that might not be achieved until the man reached his forties. In the twentieth century time spent at technical colleges or even universities, on mechanical engineering courses earned exemption from the sea time requirements and later from parts of the written examination papers.

Chief Engineer c 1867

“Oil and water don’t mix.”

In the semi-enclosed society of the power-driven merchant ship, the differences in age, vocational socialization, training and education between deck officers and engineers could lead to stresses in the social environment. The different social backgrounds from which members of the two groups were drawn and the spatial structuring of the shipboard society, on board P&O company ships, demonstrated the class and attitude differences between engineers and deck officers.

The former were blue collar skilled working class, while the latter generally had middle class origins, having become upwardly mobile in culture and behaviour during the nineteenth century. Overlaid with this were mutual resentments. On the part of commanders and deck officers, examples include the loss of control over propulsion, dislike of the smells and dirt caused by steamship engines, the lack of understanding of engineering technology, and the deck officer's dependence on the superior technological knowledge of engineers. On the part of engineers there was their perception of superior attitudes adopted by deck officers, separate messing, and the inability to rise to command.

Staff Commander, Commander and Chief Engineer ~ ss Ranchi 1928

Engineers were ill prepared for instant officer status by their shore training and initially experienced difficulties adjusting to having authority over relationships with, in particular, engine room and catering ratings from similar backgrounds. In contrast deck officers were adjusted to their social positions in the shipboard hierarchy through their time as cadets. As engineers became more highly educated technically, they could command higher wages ashore than deck officers of equivalent rank, and were often preferred for management positions, such as that of a marine superintendent. There were many ships where the two groups hardly ever mixed, either at meals or for social relaxation, contact being restricted to work requirements only. All these factors were summed up at sea by the term “oil and water don’t mix.”

Chief & Second Engineers ss Victoria c1904

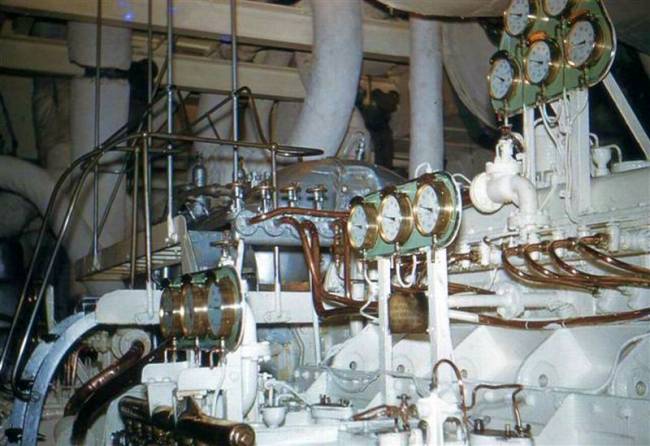

As a steamship company from the outset, P&O recognised the need to keep well manned watches in engine and boiler rooms. A large passenger liner like the ss Victoria, needed a number of engineers on each watch {12 to 4, 4 to 8 and 8 to 12, am and pm} with these men supervising the firemen, greasers and coal trimmers and tending the machinery and boilers under their control. Engineers stood watches in both the boiler rooms and engine room, with reciprocating engines and, later, turbines. The Chief Engineer would not have kept a watch but the majority of the other engineers would have done so. Passenger ships carried several certificated Second Engineers, with one in charge of each watch. Third Engineers and Senior Fourth Engineers would have allowed for further qualified engineers on each watch, with one supervising the boiler rooms. The remaining Junior Fourth and Assistant Engineers would have been employed supervising generators, pumps and steering motors, while three engineers would have been responsible for the boiler rooms. At least one Electrical Engineer would have been employed on each watch, with the Chief Electrician on day work. The Refrigeration Engineer, two Deck Engineers, two boiler makers and a plumber are also likely to have been on day work, as directed by the Chief Engineer as circumstances required.

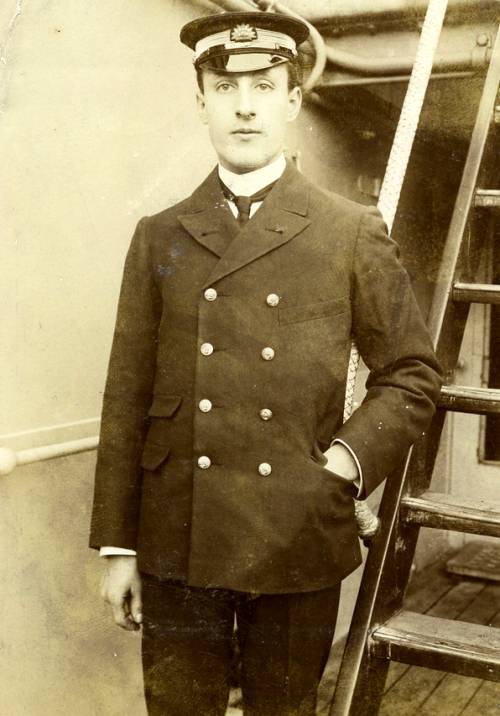

Junior Engineer c1895

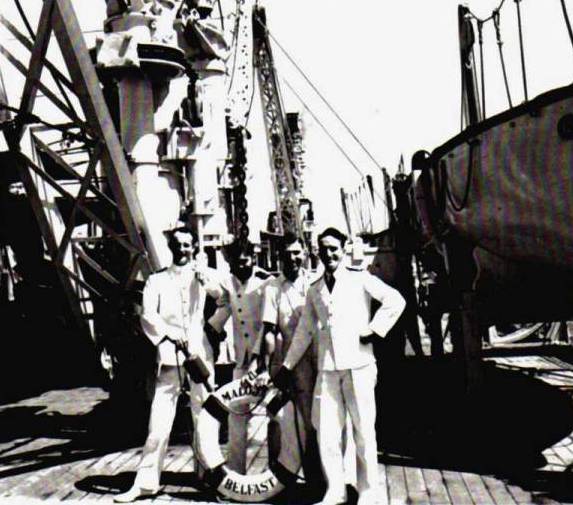

ss Maloja, Engineer Officers, 1951

Junior Engineer Officer Terry Wild, On Joining P&O from the Royal Navy in 1954

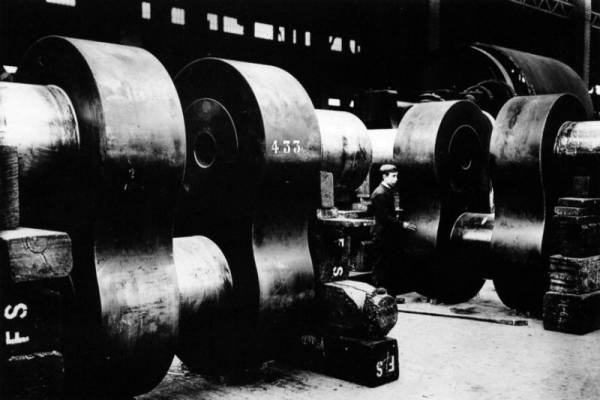

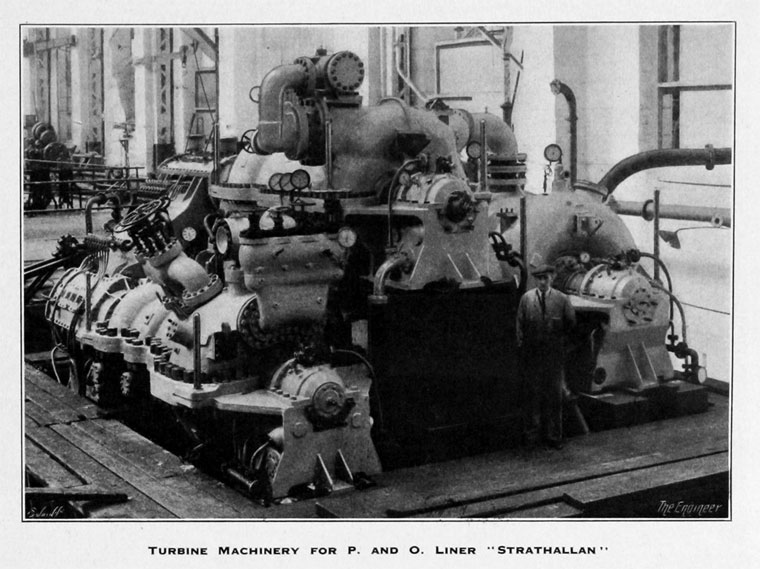

By the late 1800's, the marine steam reciprocating engine had reached it's pinnacle, and there seemed to be no further avenue to explore to improve efficiency. In order to get more power, engines had to be bigger, but the size of the moving components was imparting vibration, both to the engine, causing it to breakdown, and to the ship, which was particularly unwelcome aboard P&O's lavishly decorated ocean liners. It was not unusual for ship's reciprocating steam engines to be replaced, due to wear and vibration, after relatively short periods of operational service. It was therefore necessary to find a means of propulsion that produced less vibration - and noise.

Sections of the crankshaft of a large marine steam engine.

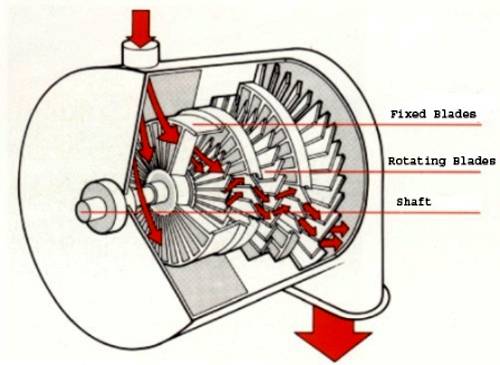

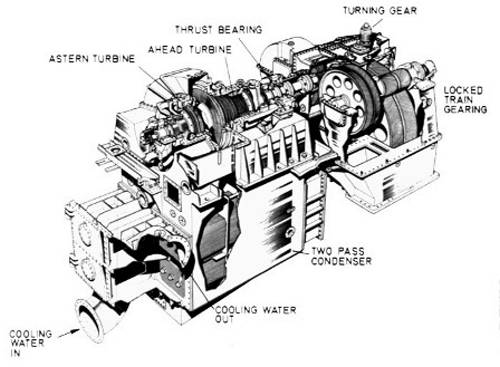

In 1884, Charles Parsons patented the first workable marine turbine.

A simple turbine schematic of the Parsons type, with rotating and fixed stators.

Steam pressure drops by a fraction of the total across each pair; the stators growing larger as the pressure drops.

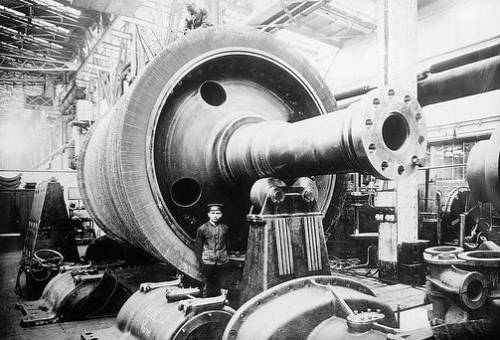

Section of an early large Marine Turbine

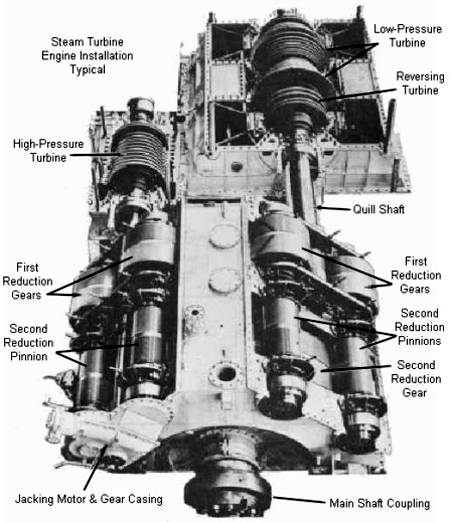

The gearbox represents a significant element of the engine and in some cases is the largest single unit.

The condenser is cooled with sea water.

Iberia's Port Gearbox

Third Engineer and Terry Wild. main engine control, ss Chusan, 1956

Oronsay's Engine Control Station

Arcadia's Boiler Room

Iberia's Generator Flat

Assistant Engineer Bill Hutton ~ ss Strathnaver 1957

Third Engineer Bill Hutton ~ ss Canton 1960

Third Engineer Edward A.Pooley ~ ss Arcadia 1957

'You hold it, I'll give it a tap!'

Terry Wild, JEO on left

'Pour-Out' ~ Dave Twinning, 2nd Engineer Officer in monocle.

ss Stratheden, Engineers off duty, 1963

Third Engineer Officer Terry Wild, Fine Dining aboard ss Iberia, 1965

Oil and water do mix!

Officers from ss Patonga outside St Patrick's Church, Fortitude Valley, Brisbane on the 11th May 1959, for the wedding of James O'Sullivan, Third Engineer Officer and Joan Corderoy.

From Left to Right: Jack Sadler (Chief Eng), Pugh (First Officer), John Hall, Best Man (3rd Eng), Frank Stone (Radio Operator), Mike Hill, (2nd Officer) James O'Sullivan (3rd Eng), wife Joan Corderoy, Ian Bates (2nd Eng), Captain Wood.

An article from The Straits Times, dated 31st October 1906

The Batti-Wallahs Society

Aka: the Marine Electrical Engineers Association

A Batti-Wallah is a ‘harijan’ – on the very bottom rung of the Indian caste system, an ‘untouchable’ whose only task in the sum total of human endeavour was to fill and light the oil lamps at dusk every day.

The name was also applied to P&O Engineers by the Indians who regarded the powerful searchlights playing on the shore as the work of magicians!

The P&O Engineers formed a society in London, holding a monthly lunch, usually addressed by some worthy speaker from industry and the scientific community.

The first President of The Batti-Wallahs Society was LAWRENCE MAXWELL WATERHOUSE, born in 1868, and educated at Craigmount School and Heriot-Watt Technical College, Edinburgh. For some years he was Lecturer in Physics and Electrical Engineering at Brighton Technical College and Croydon Polytechnic, while also undertaking some consulting work in connection with various electric lighting schemes. He then joined the P&O Steam Navigation Company as a sea-going electrician.

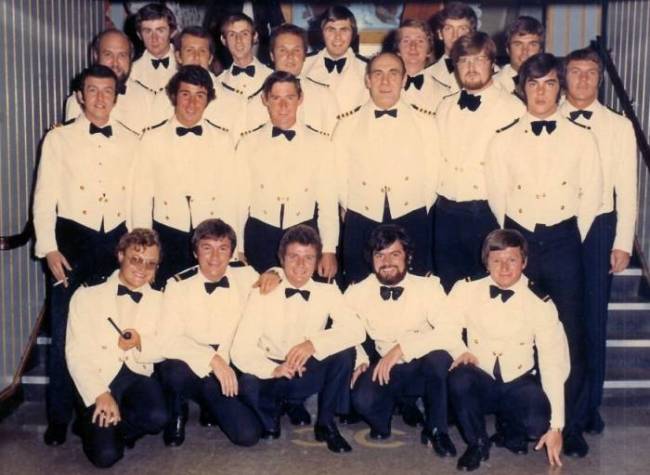

ss Oronsay's Engineers c 1972

Front Row from LHS:- Chris Benham Ass Engr, Bruce Lindon 4th Engr, Cameron Fortune Asst Elect, Bill “Willy” Carr Asst Engr, Chris Freeman Asst Engr.

First Row from LHS:- Roger Palmer Ch. Elect, John Thow 3rd Engr, Jeff Connolly Snr 2nd Engr, John McLeod Ch. Engr, Paul Steele Asst Engr, Don Hallam Asst Elect, Graham “Chuck” Tuck 4th Engr.

2nd Row from LHS:- Colin Wright 3rd Engr, Tim Davies 2nd Elect, Paul Hudson Asst Engr, Geoff Horan Asst Engr, Trevor Finch 3rd Engr.

Back Row from LHS:- Peter “Taffy” Morgan Asst Elect, Keith Radford Asst Engr, Kevin “Morg” Morgan 3rd Elect, Jon Harvey Asst Engr.

I am grateful to Keith Radford for the photograph, and for putting names to faces.

ss Arcadia's Engineers ~ c1973 - with the new P&O cap badge.

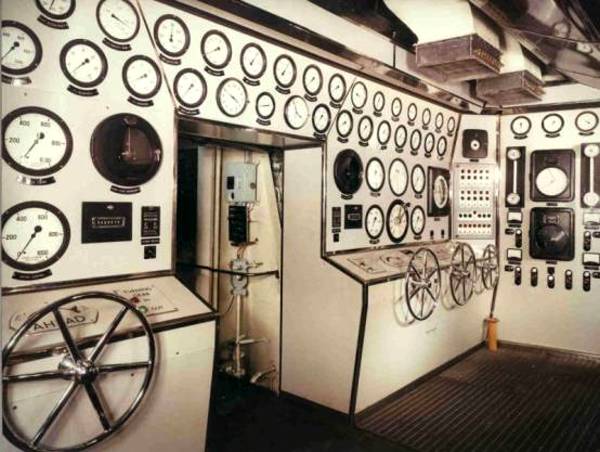

Engine Room Control Station ~ ss Canberra

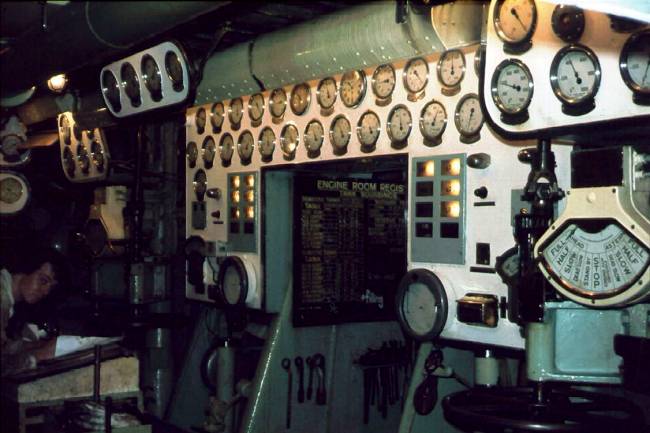

Engine Room Control Station ~ ss Oriana

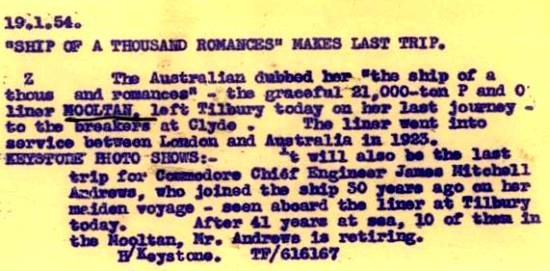

ss Orsova

Marine Diesel Engines

The diesel engine of choice in P&O's Cargo ships was the Doxford opposed piston engine. William Doxford and Sons began building marine steam engines in 1878, when the original engine and boiler works were constructed. The first engines were compound, triple, then quadruple expansion, and later still turbines. In 1887 they built a single screw torpedo boat, which attained a speed of 21 knots, the highest speed recorded for that type of vessel.

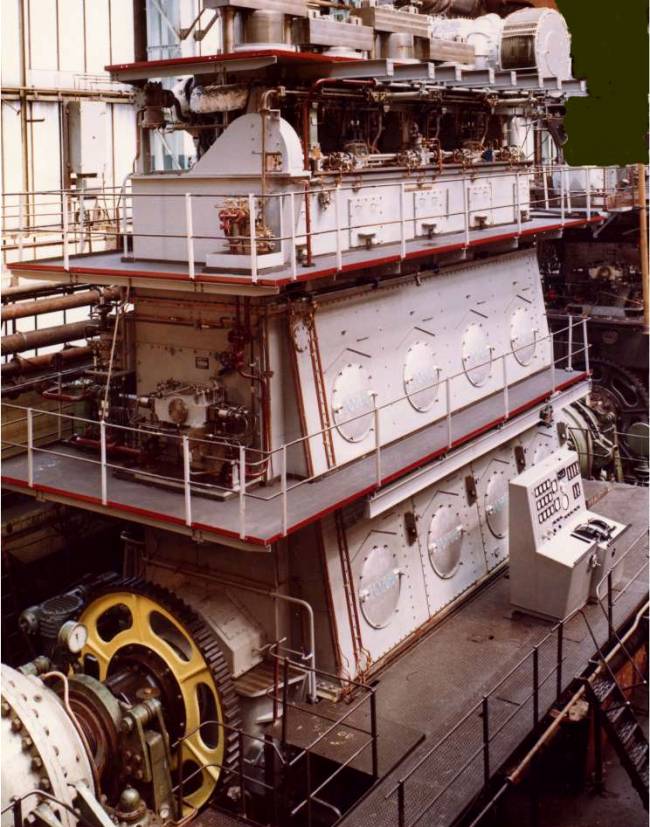

Doxford Opposed Piston Marine Engine

Doxfords built vertical, opposed piston two-stroke diesel engines for ships, up to 8,000 bhp, and their design became a standard fit for P&O cargo ships until the licence-built Sulzer and B&W engines challenged their position in the 1960s. The last Doxford engine design, which was known as the 58JS, was in response to escalating fuel costs, and was developed to provide compact direct drive machinery for smaller ships which could then run on cheap low-grade heavy fuel oil.

Doxford J-Type Marine Engine

The Photographs of Engineer Officer Ted Sapstead

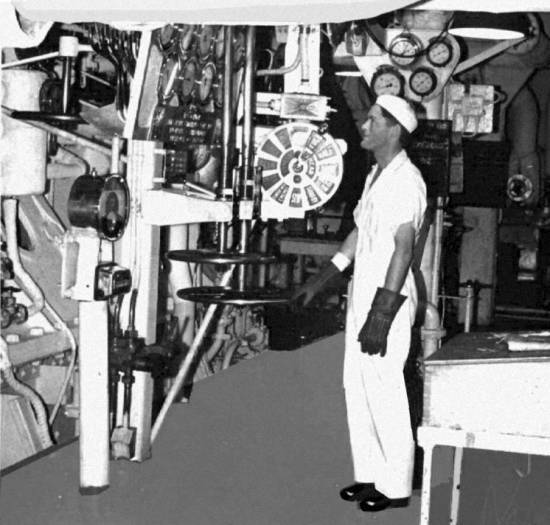

Ted Sapstead at work on board ss Strahmore in 1957

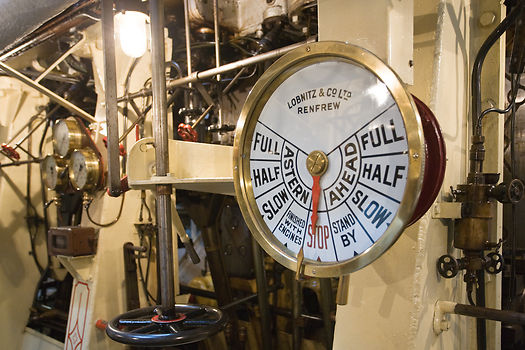

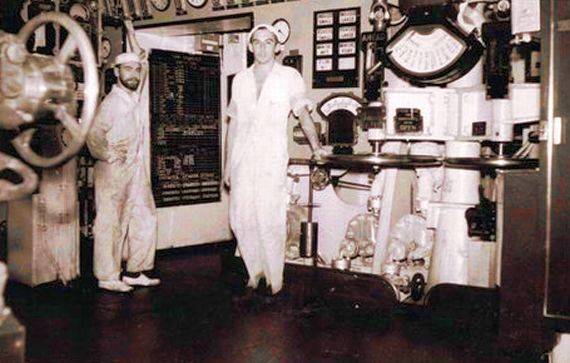

ss Strathmore's Engine Controls

ss Strathmore's Engineer Officers 1957/8 - with Ted Sapstead third from the right.

Heave Ho!

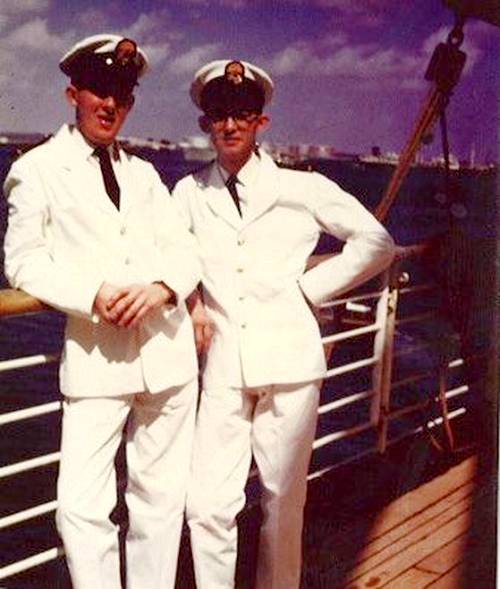

Electrical Officer, Ted Wright & Ted Sapstead ss Strathmore 1958

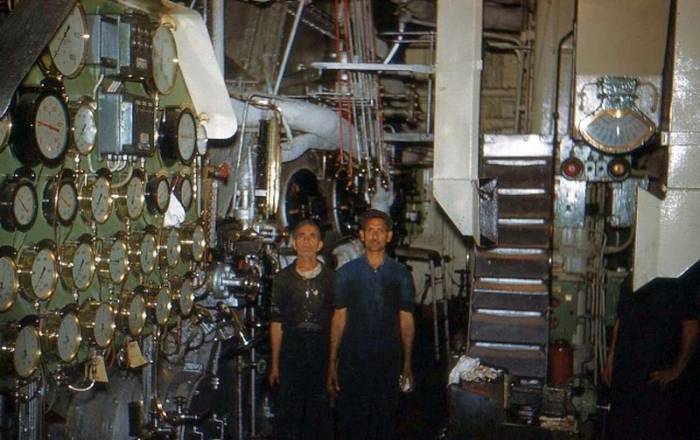

ss Strathmore's Boiler Room with the Boilermaker in the centre of the photograph, flanked by two Pakistani Engine Room Crew.