Please Note: The house flag and word mark 'P&O' are Trade Marks of the DP World Company https://www.dpworld.com/

"The Bombay crews are usually preferred by P & 0 Officers, though many from Calcutta are good."

“Lascar labour was indispensable to British industry. Without their labour the British Merchant Fleet could not have functioned. They were

responsible for transporting raw materials and manufactured goods, as well as passengers, across the world within Britain’s imperial economy, and

Britain’s wealth and prosperity could be said to have been built on the backs of these poorly paid sailors.”

Dr Rozina Visram - Asians in Britain: 400 Years of History

"To be aboard a Company's ship once more, to see the familiar red and blue of the Lascar's uniforms, to hear the Tindal's soft-spoken 'Salaam, Sahib'; in a word, to be on my own ground and amongst my own people after my long exile....."

Commodore D.G Baillie, P&O, writing in A Sea Affair

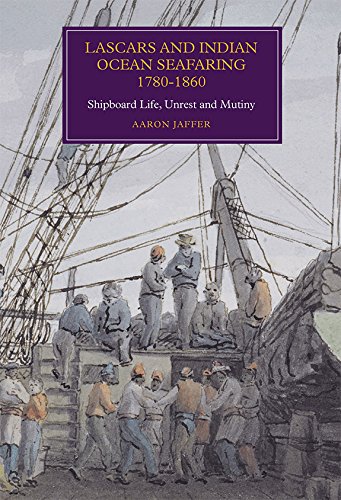

Once vital, today, Lascar Sailors remain nigh on invisible in historical accounts of maritime trade and empire, and are remarkably under-represented in the emerging scholarship on global histories, trans-national identities and colonial networks, to which their stories are integral.

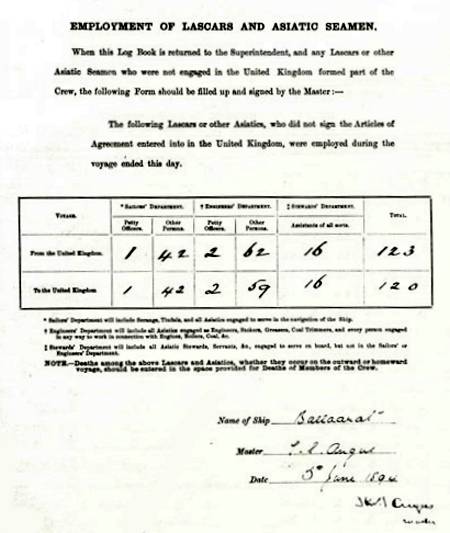

Their lives remain fragmented in the archives, ciphers glimpsed rarely in ship's logs, Admiralty records - and in the Navigation Acts that governed their employment.

Finding Lascar stories in historical records is difficult. There are very few first-hand accounts written by Lascars - only bureaucratic, European references in East

India Company records, muster lists and logbooks, and the occasional parliamentary records.

Sadly, largely forgotten today, Lascar sailors are commemorated in the naming of a modern housing development in London's East End...

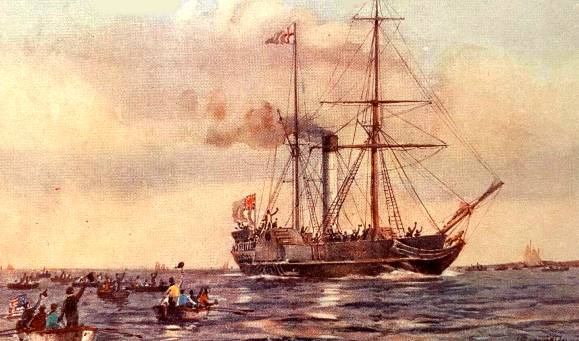

From the 17th Century, Britain's East India Company, which was set up by private merchants in 1600, by Royal Charter, to establish trade links with India, employed Lascar sailors aboard its 'East Indiamen'.

An East Indiaman

By the 18th Century, the East India Company held a monopoly on the lucrative maritime Eastern trade, and had built factories and forts, manned by its own private armies, right across Southern Asia.

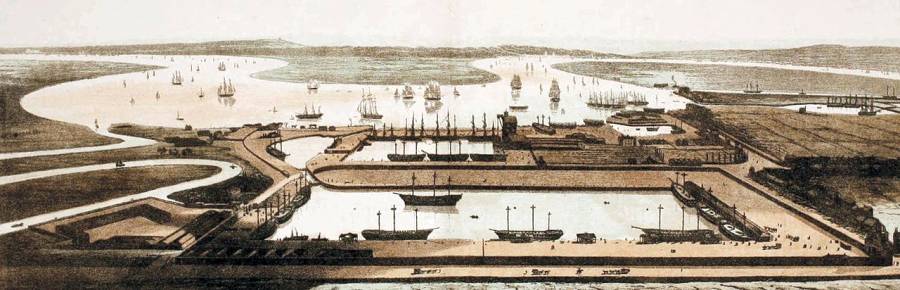

London's East India Docks, c 1803 An Act of Parliament set up the East India Dock Company, promoted by the Honourable East India Company.

The East India Company traded mainly in cotton, silk, indigo dye, saltpetre, tea, and opium. However, it also came to rule large swathes of India, exercising military power and assuming administrative functions, to the exclusion, gradually, of its commercial pursuits.

EIC Bridgewater under jury rig, approaching Madras

During this period of intense growth, over 220 East India Company ships voyaged from Britain to the East, returning manned by predominantly Asian crews.

138 Lascars are reported arriving in British ports in 1760, rising to 1,403 in 1810.

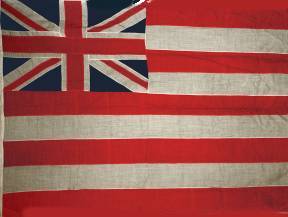

East India Company Ensign

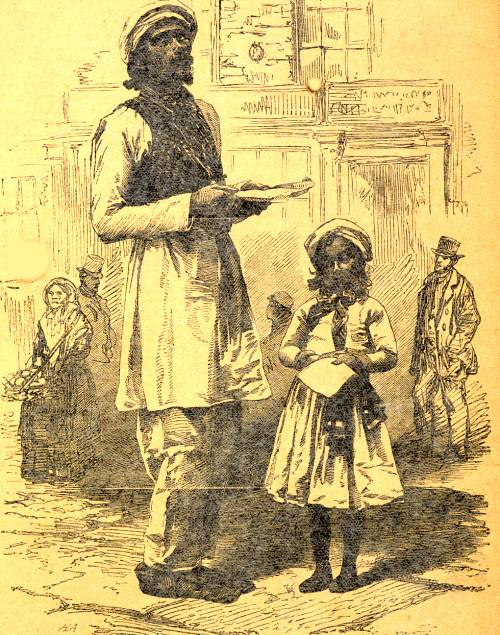

Once they reached London, the East India Company was in the habit of abandoning its Lascar sailors, leaving them to their own miserable devices, frequently forcing the poor fellows to beg for meagre loose change, as depicted in this fine painting by the English artist William Mulready.

A boy giving money to some poor Lascars.......

.jpg)

"Train up a child in the way he should go, and when he is old he will not depart from it."

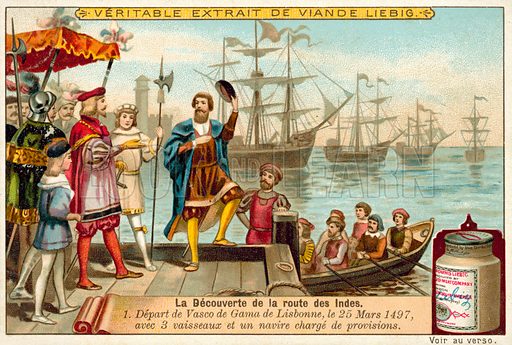

The first recorded European use of the word 'Lascar' predates the East India Company by at least a hundred years, and can be found in records of the employment of Asian seamen aboard Portuguese ships in the early 1500s.

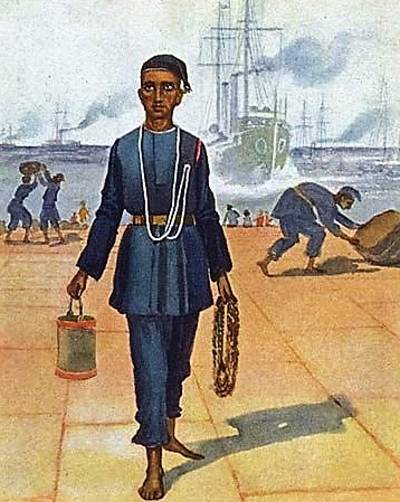

The term is not in use today, but as a period term it identified men who were engaged at ports in India, typically Bombay and Calcutta, who were signed on Ship's Article, under the special terms of a Lascar Agreement.

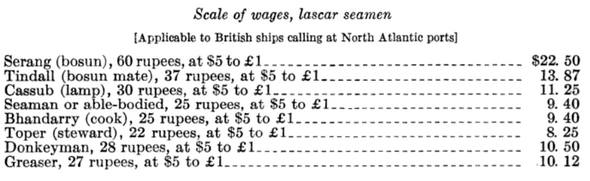

The Indian Government’s Merchant Shipping Act of 1880 authorized pay amounting to half that for British seafarers. The rate was justified by the lower remuneration to workers in India.......

Less space aboard ship was allotted to Lascar crews, though the most important saving on Lascars recruited to trans-oceanic vessels came from lower wages......

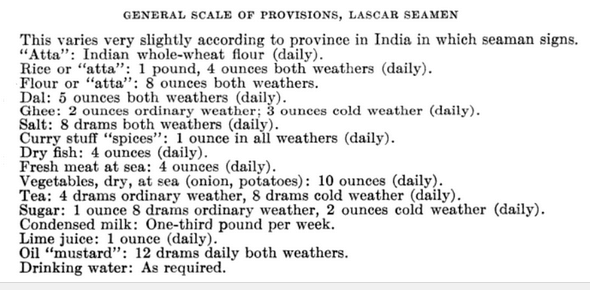

Victualling aboard ship was poor: A diet of rice, flour, dhall, ghee, curry stuffs, dried fish, vegetables, and a little meat deferred to Lascar cultural preferences and religious practices. These comestibles were cheaper for the shipowner to provide than the standard seafaring fare of “salt pig”, dried peas and soft bread or hard tack biscuits.

Germany's Hansa Line recruited 4,000 Lascar sailors annually, making the company the second largest employer of Lascars after the P&O Steam Navigation Company.

From the time European ships first sailed into the Indian Ocean, they relied on the knowledge of local seafarers.

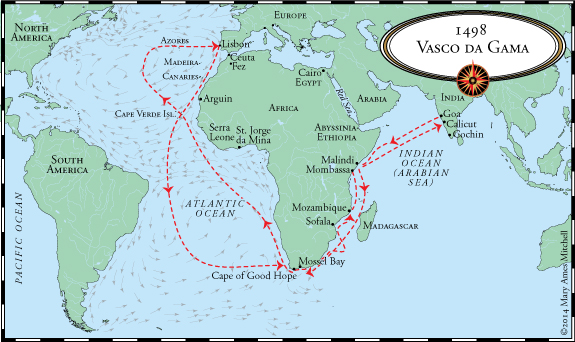

When Vasco de Gama’s four ships crossed the western Indian Ocean in 1498, they were guided by a Lascar pilot.

The maritime knowledge, seafaring skills and labour of Indian Ocean sailors was essential to European ships and Empires throughout the following five centuries.

Departing Lisbon aboard the San Rafael, together with three smaller ships loaded with supplies, on 8th July 1497, Vasco da Gama reached Calicut in India, the main port of the ruling kingdom of Samoothiri, on 20th May 1498, via Malindi, where he secured the services of an experienced Lascar pilot.

Calicut, From the Civitates Orbis Terrarum Atlas. Illustrated by Georg Braun and Franz Hogenbergs

According to legend, the Portuguese filled their holds with loot, mostly spices, that would be worth sixty times the expense of their expedition when they reached home. Treated badly by his Portuguese masters, Da Gama's Lascar pilot jumped ship, and without his expertise, faced with monsoon winds and treacherous seas, the voyage home proved disastrous. Scurvy was rife, and Da Gama lost over half his men to the disease.

A century after Vasco da Gama's first foray, Lascars sailors from the ‘East Indies’, proved vital to the English East India Company, and throughout the 17th and 18th centuries as it developed trading posts - and fought for a dominant position in the lucrative Asia trade.

During the long trading voyages to Asia, many European sailors died or were pressed into service with the Royal Navy, who frequently boarded Merchant Ships, looking for experienced men. Such activities were not limited to the British - the Portuguese, French, Dutch and Danish all regularly recruited, and at times coerced and even kidnapped, local sailors. During this period, over 220 EIC - East India Company ships sailed from Britain, with mixed European and Lascar crews, signed on in British ports. Then, when their ships reached the Indian Ocean, they tapped into the well established, local, maritime labour-gang system, whereby Ghat Serangs, acting as employment brokers in south Asian ports, supplied whole crews, complete with petty officers - Serangs and Tindals.

Lascars worked on EIC ships sailing to Europe, round the Indian Ocean, east to China and, later, south to Australia. The Asia trade relied on seasonal monsoon winds, which meant Lascars spent months in Europe between voyages. A transient community soon developed in London, Liverpool, Cardiff and Glasgow. 138 lascars were reported arriving in British ports in 1760, rising to 1,403 in 1810. Some married English women, but all were required to return home, and were banned from working in Britain.

Lascars were forced to rely on the EIC for subsistence and a passage home, with the result that many ended up in debtors’ prison or worse.

Lascars were necessary to the shareholders of the EIC - but troublesome to the British state.

They were nominally free men, but the British state worked continually to contain and control them.

By the beginning of the NapoleonicWars (1803-15), over a thousand Lascars had arrived in the Port of London. Most arrived on East India Company ships, later arriving on P&O and Clan Line vessels. Despite the fact that the East India Company had, in most cases, brought the seamen to London, it was reluctant to take responsibility for them. The government intervened with initiatives to return the Lascars to India, passing the Merchant Shipping Amendment Act in 1855. This meant the East India Company was obliged to take responsibility. In 1871 Board of Trade appointed transfer officers with the purpose of sending back Asian seamen via India-bound ships. In 1894 another law was enacted to ensure Lascars returned to India. Officers who engaged in crackdowns on Lascars in Britain, claimed to be motivated by humanitarian aims: they hoped to prevent potential deserters from wandering into lives of destitution on the streets of Britain......

In a letter dated 28th November 1809, Hilton Docker, a medical doctor to the Lascars, described their conditions:

‘The Natives of India who come to this country are mostly of bad constitutions. Numbers are landed sick from the ships, where they have been ill, and when they arrive (usually at the latter end of the year) they have to encounter with a climate and season to them particularly pernicious which most frequently increase their disease.Those who are landed in health are of course exposed to the same danger of climate and season and in addition almost all of them give way to every excess in drinking and debauchery, and contract to a violent degree those diseases (particularly venereal) which such habits are calculated to produce.’

Given the way poverty and prejudice limited the opportunities for socialising, none of this should be very surprising.

Like sailors everywhere, stranded Lascars seeking entertainment often frequented pubs, gambling houses and prostitutes. For example, Indian Lascars were involved in an affray involving Chinese sailors in Stepney in 1785. Lascar seamen also got into conflict with the locals:‘… in 1803, three Lascars, armed with cutlasses, broke into the City of Carlisle public house in Shoreditch High Street, seeking to recover the substantial sum of £150 they claimed that local sex workers there had stolen from them.’

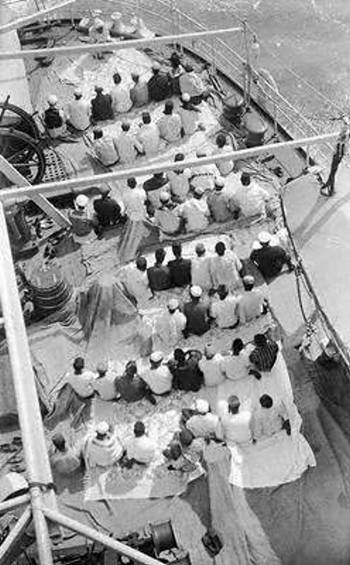

Lascar crews comprised men of diverse religious and regional backgrounds, the majority, however, were Muslims.

Lascars observed the month of Ramadan each year by the sacrificial killing of a domesticated animal, a sheep or goat, traditionally provided by the ship's chief officer, who was then invited to partake.

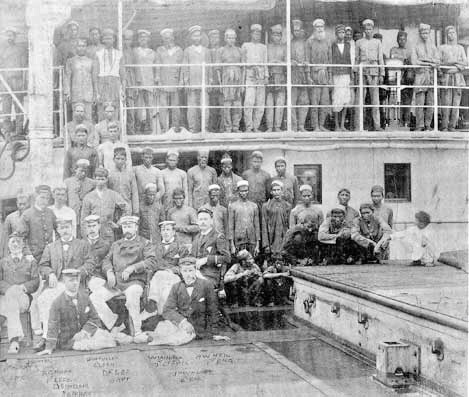

Bank Line Chief Officer & Lascars

Fasting during Ramadan greatly restricted a Lascar sailor's ability to perform the strenuous duties frequently required on board ship.

Abstinence from all food and drink, including water, from dawn to sunset, required the Bhandary, the crew cook, to prepare a pre-fast meal known as suhur.

Lascars at prayer on board the Bengalen, c1910

ss Bengalen

Daily prayers were an important part of Lascar life on board ship, and generally preceded by a visit to the bridge in order to ascertain the relative bearing of the holy city of Mecca.

Religious concerns associated with food were often cited as a potential cause of conflict between Lascars and their European officers. When Charles

Nordhoff, the American journalist and writer, recalled his time on a country ship, he claimed that ‘‘so slight a misdemeanour on the part of any of the

Europeans as handling any of their cooking utensils, or drinking from their water cask, would produce an instantaneous remonstrance’’. Officers

undoubtedly became frustrated with attempts to maintain ritual cleanliness. Storing food separately, keeping eating spaces apart, and allowing

Lascars to butcher their own animals would have presented many difficulties aboard a cramped sailing vessel. Europeans also implied that religious

strictures against certain foodstuffs had no place at sea. Captain Crawford of the Investigator expressed surprise at the refusal of Muslim sailors

to eat turtle ‘‘even when in a dying state from the Scurvy and suffering under the greatest privations on board ship’’. Other commanders are reported

to have complained about the practice of fasting during Ramadan on the grounds that it hampered a crew’s ability to work. Captains permitted their

Lascars to hold various religious festivals at sea. These involved feasting, music, and processions. Anthony Mactier described one which took place

during the voyage of the Surat Castle to India in 1797. The ceremony, which may have been associated with Muharram, featured Lascars who

‘‘intoxicated themselves with Opium and wounded their breasts and other parts of the body with Swords, dancing all the while to the Sound of the Tom

Tom’’. The licensed disorder associated with such occasions may have provided Lascars with a means of releasing tension. Whether they ever turned

sour or got dangerously out of hand is unknown. As Margaret S. Creighton has shown, this was always a risk when allowing ‘‘Crossing the Line’’

festivities to take place.

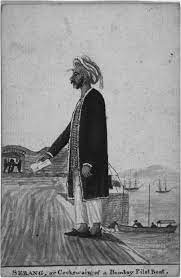

Serangs appear to have taken centre stage during many of these events. Certain ceremonies involved the Serang leading his men aft to pay their

respects to the captain. ‘‘On the first evening the new moon makes its appearance’’, wrote George Bayly whilst in command of the Hooghly; ‘‘all hands

dress themselves in their best garments and headed by the Serang come aft on the quarter deck, make their salaam to the Captain and Officers and

return forward on the opposite side of the deck’’. Regrettably, observers seldom described the manner in which these gestures were delivered or

whether the occasion was ever used to surreptitiously insult the captain. A passenger travelling to India aboard the Reliance in 1828 drew attention to

the garb worn by Serangs and Tindals during a similar ceremony. Alexander Gardyne declared that the petty officers on board his ship ‘‘were

positively irresistible, the Grand Turk himself could not have made a greater dash than did Serang Ally & his Vizier Abraham’’. Although many of these

customs reaffirmed the authority of the captain, they could also highlight his distance from the crew whilst cementing the Serang’s position at its head.

From, ‘‘Lord of the Forecastle’’: Serangs, Tindals, and Lascar Mutiny, c.1780–1860 by A Aron J Affer

From The New Zealand Record

LASCAR RELIGIOUS FESTIVALS

Three times in a year the Moslems have special religious festivals: they celebrate these and each time they are allowed a day's holiday in the ship.

A word about these holidays may be of interest.

In the Calendar of Islam, Ramadan is the ninth month and for all Moslems it is a time of fasting. Through the month, from sunrise to sunset, neither

food nor drink may pass the lips of any Moslem, nor is he allowed to smoke. It is indeed a rigorous test and is strictly observed.

They believe that it was during this month that God sent from the Seventh Heaven, by the Angel Gabriel, the Holy Koran to be revealed to the Prophet Mahommed. It is upon this Book that the Mahommedan religion is largely based. It is noteworthy that the Koran was sent by the hand of the Angel Gabriel, for the Angels, the Prophets and even Jesus Christ all figure in the Islamic faith.

On the day following the end of Ramadan, the first day of the month, Saual, comes the first Moslem feast day, Ramadan-id. The burra din, or festivals, are often celebrated by a religious service, by feasting and, ashore, by the purchase of raiment and the donating of gifts.

The second festival takes place on the tenth day of the month Zihlhaj, or the month of the Pilgrimage. It is only during this month that the pilgrimage to Mecca takes place, culminating in various ceremonies there between the seventh and tenth days.

The last day is the feast day and is celebrated all over the Moslem world.

The day is known as Bukra-id, bukra meaning goat, for on this day a goat, or sometimes a sheep, is sacrificed by having its throat cut in the approved manner.

The appropriate passage from the Koran is read out during the ceremony. The sacrificed animal then provides the main dish at lunch time. It celebrates the sacrifice of Ishmael, who with most Moslems takes the place of Isaac in the narrative dealing with the abolition of human sacrifices. In actual fact a goat or sheep is often slain on other feast days.

The last festival, though it is not celebrated by all Moslems, is in the month of Mohorram, usually on the tenth. It is connected with the murder of various of the early followers of Mohammed and especially with that of his grandson Hussein.

Ashore a religious procession often takes place on this day and, before the War, the crews of ships at Tilbury often staged one.

The time of the year that these festivals takes place is not constant. This is due to the fact that Moslems use the uncorrected lunar calendar so that their years are never the same length as ours.

Written by M. Watkins-Thomas in P&O's house magazine About Ourselves, first published September 1955

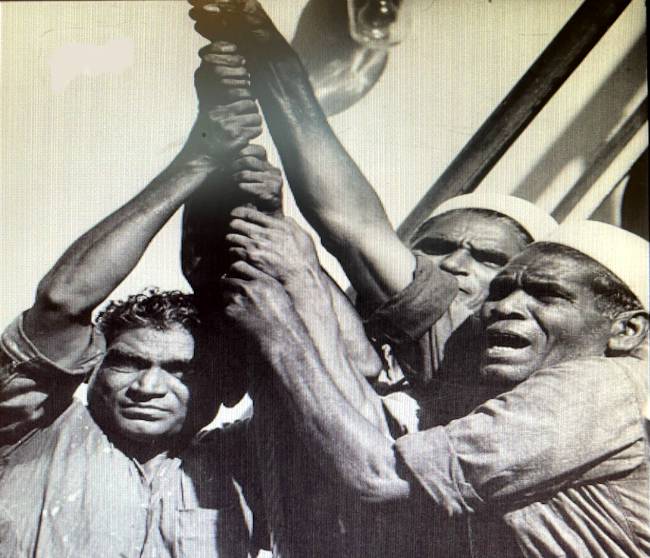

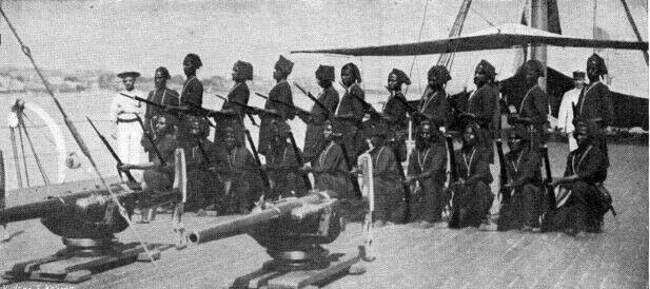

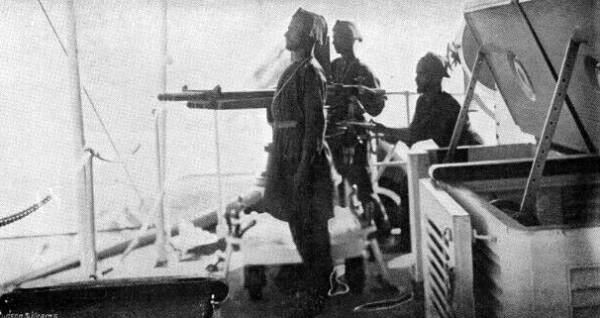

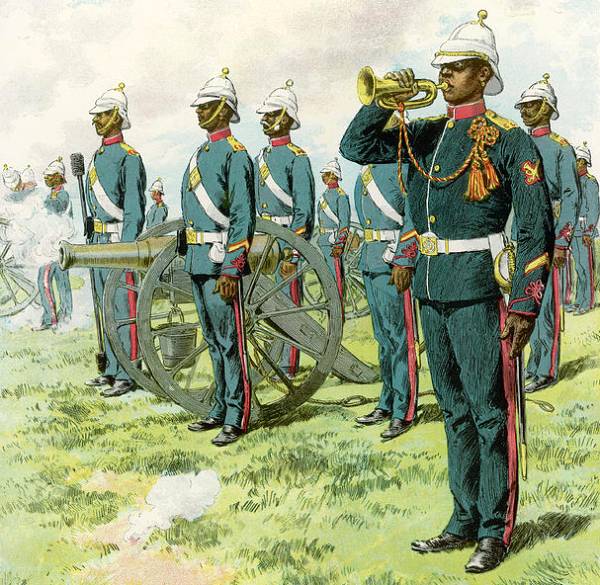

Many Lascar Sailors received weapons training in the Royal Indian Navy, 1612 - 1947.

Lascars at musketry drill in 1897

Lascars training with a Nordenfelt machine gun in 1897

Gun Lascars from India and Ceylon saw active service with the East India Company

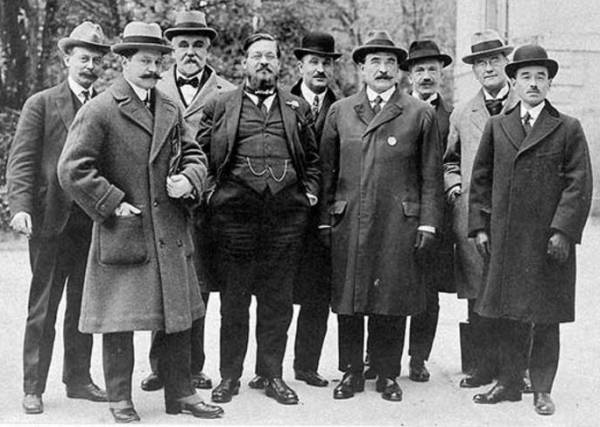

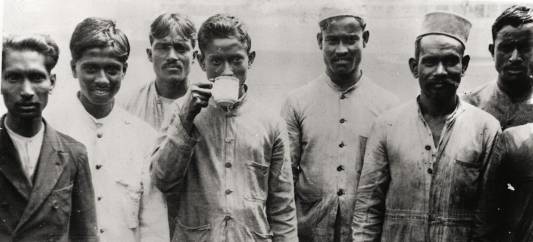

By 1914 and the outbreak of the First World War, Lascar sailors made up 17.5% (or nearly 1 in 6) of seamen in the British Mercantile Marine. A figure that grew during the war. As sail had given way to steam in the 1800s and British Imperial power hardened, employment regulation grew and the relative protection and support of the Serang system was broken.

By the outbreak of war, Lascars had become integral to Great Britain's maritime empire and global trade.

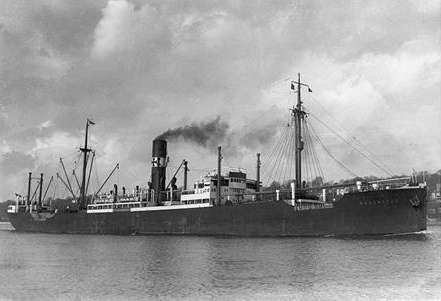

The pressures of war led Britain to dramatically increase Lascar recruitment. Lascars played an increasingly significant role in keeping hospital and supply ships running, carrying essential cargo, vital food and ammunition, through danger zones, while facing significant personal risk.

Their poorly defended ships, targeted by an increasing number of German U-Boats, came under sustained gun and torpedo attack.

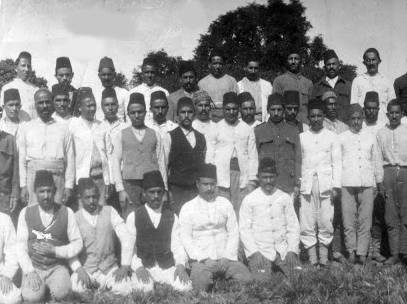

According to India Office records, some 1,200 were captured and imprisoned in enemy countries - the majority in Germany.

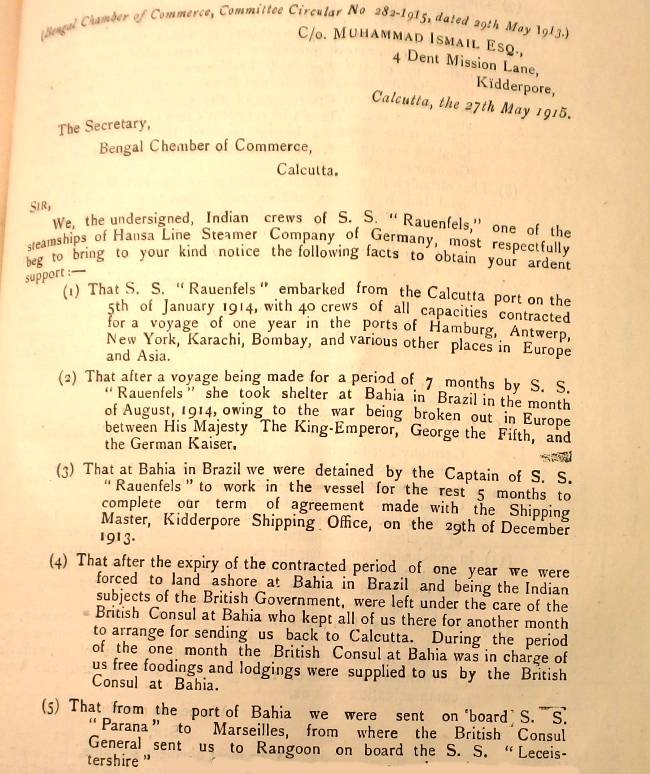

From 1914, Lascars employed in German and Austrian vessels, like the ss Rauenfels, were either discharged and repatriated by British consuls, or made civilian prisoners of war.

Official records list the hundreds of Lascars who died or were captured and interned due to enemy action. The majority of POWs were imprisoned in Zossen-Wünsdorf, Havelberg and Güstrow.

Lascar letters and interviews reveal the inadequate living conditions, ill-treatment, hard labour and lack of food in the German prison camps. They were often made to work in munitions factories. Owing to a lack of medical care, many men died of tuberculosis, aggravated by the living conditions in the camps, while some became disabled due to accidents at work. Charitable organisations sent parcels of food and warm clothing to imprisoned Lascars, via The Red Cross, similar to the arrangements made for interned soldiers.

In the aftermath of the First World War, the British Board of Trade and the India Office, organised the repatriation of Indian seamen who had been taken prisoner or injured.

Lascars serving in British ships, seized in enemy ports in 1914, were often interned for the duration, while Lascars serving in British ships destroyed by enemy action, were made prisoners of war.

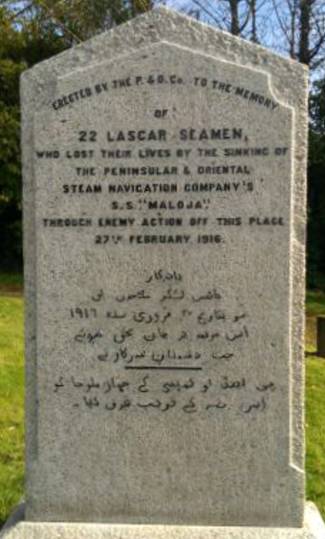

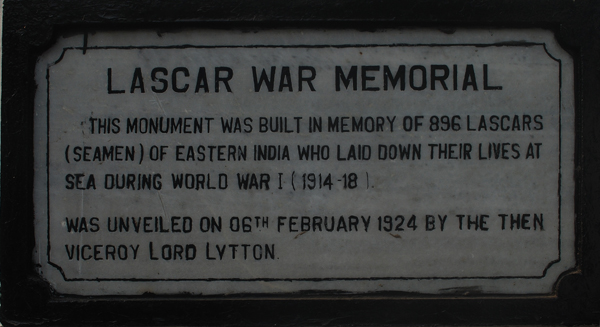

Sadly, Britain has very few individual memorials to Lascar sailors.

.jpg)

Photo: Daily Mail

However, the P&O commissioned a memorial to the twenty-two Lascar seamen who lost their lives when the ss Maloja was sunk in the English Channel.

In February 1917, it was suggested that Lascars should be included in proposals to grant war medals to the Mercantile Marine. Lascars were to be eligible for the medal under the same conditions as all British seamen.

Somewhat cynically, this was seen as a useful recruitment tool.

A group of Indian sailors was present at the unveiling of the Tower Hill Memorial in London on 12th December 1928, to honour the merchant mariners who lost their lives in the First World War. The memorial commemorates over 3,300 sunken ships and a loss of over 17,000 lives, from Britain and the Empire. However, the vital contributions of Lascars to the war effort have remained largely unrecognised.

Florian Stadtler, University of Exeter

.jpg)

Photo: Indian Navy

The Lascar Memorial on Calcutta’s Maidan, is dedicated to the memory of the 896 Lascar sailors, who died serving in ships of the British Mercantile Marine, during the First World War.

The Hooghly River at Calcutta, by Frank Clinger Scallan

Frank Clinger Scallan was born in Calcutta in 1869 or 1870. The little that we can glean from one or two existing biographical notes, tells us that he completed his schooling at the Calcutta Boys’ School, which was founded around 1877.

Following the Great War, the Trades Unions, operating at ports throughout the United Kingdom, forbade a coloured man from signing on a ship when there was a white applicant for the same position. Under the Aliens Act of 1923, all Lascar sailors were labelled 'Aliens' and barred from serving aboard any state-subsidised ship - ships that received Government support during the Great Depression, in order to, literally, keep them afloat.

By 1936, after years of exploitation, the International Federation of Trade Unions Congress recommended the regulation of Lascar sailors' working hours. Lascars, it acknowledged, were still expected to work longer hours than their white European counterparts on the same ship - and for considerably less pay.

In December 1936, the President of The Board of Trade was asked whether he was aware that the owners of steamships discharging their white British seamen and substituting Lascars, were reportedly saving the sum of £45 per ship per month in wages – while, at the same time, increasing the number of crew by twenty.

He was duly informed, by the ship-owners, that there were ‘additional costs incurred in the employment of a Lascar crew – one example being the additional cost of victualling – and furthermore, in accordance with the National Maritime Board’s decision, ‘rates of wages did not apply to Lascar crews who were engaged in India on Lascar Agreements.'

According to The India Office, no such agreements existed – agreements were made either through a Serang, or directly with the master of the ship as to the wages paid to Lascar seamen.

Seafarers were the world’s first globalised workforce, and thus the first to be effectively exploited. Since medieval times, ship-owners have taken full advantage of the availability of cheap foreign labour, which has kept wages low – thereby causing unnecessary incidents of racial tension amongst seafarers.

The All India Seamen’s Federation (AISF) was formed in 1937, bringing together the Indian Seamen’s Union, Indian Quartermaster’s Union, Bengal Mariner’s Union, Seamen’s Welfare League of India and Karachi Seamen’s Union to form one of the largest federations of Lascar unions. It was instrumental in negotiating a settlement with the British Government and ship owners to resolve Lascar strikes in 1939 and 1940. As part of that settlement, Lascar pay and working conditions improved.

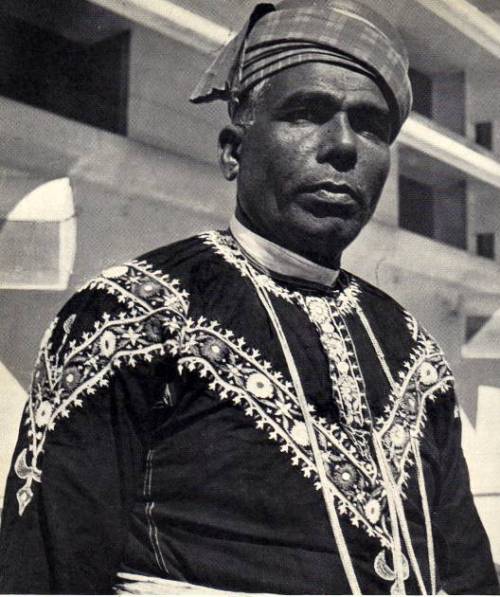

Aftab Ali in 1936

The negotiating skills of Surat Alley and Aftab Ali were key to breaking the deadlock between British ship owners and striking Lascars in 1939.

In 1939 the Board of Trade officially recognized the AISF, and the Government of India urged ship owners to follow suit.

Writing in 1939, Dinkar Desai, the acclaimed Indian poet, writer, educationist, and political activist, described Lascars as "the most exploited vagabonds of the sea"

By the outbreak of the Second World War, there had been a hardening of attitudes by Lascar sailors, driven by their country's determination to rid itself of British rule, and claim its long overdue independence.

1939 saw an unprecedented wave of strikes by Lascar sailors. Hundreds simply refused to work under the shipowners' conditions - unless they were awarded a pay increase and a war risks bonus, similar to their white shipmates. By December 1939, hundreds of Lascars had been charged with breaking their contracts and imprisoned. Their motives are considered by some to have been opportunistic. They were motivated as much by a keen sense of opportunity as by their abysmal conditions of work and pay.

The engagement of Lascar crews in India was governed by the Indian Merchant Shipping Acts. For the British government the most important provisions were those requiring that crews could not legally be discharged in the UK, although the crew of a ship arriving in the UK could transfer its crew to a departing ship. This procedure had been devised to ensure that Indian seamen would not become resident in the UK. Imperial citizens who became UK-resident could ship out of Britain on UK wage rates - while the whole point of employing Lascar crews was that they were paid one-quarter of the wage of white British seamen. In the Autumn of 1939, the Lascars grievances over wages and related conditions, prompted strikes aboard ships in British, South African, Burmese and Australian ports. Shipping companies employing Lascar seamen anticipated difficulties, and four days before the outbreak of war, a London meeting of the principal employers agreed to pay a 50 per cent bonus on existing pay rates from the day hostilities began. The terms of the offer were immediately cabled to the owners' agents in Bombay and Calcutta, who then began engaging crews under the new terms.

Unlike 1914, 1939's Lascar seamen did not regard the war as 'their war'- the growing demand for Indian independence was of far more importance. At the outbreak of the Second World War, there were 50,700 Lascar sailors in the British Merchant Navy, making up 26% of the labour force. There were still big differences in pay, with white seamen earning on average seven times as much as Lascars, causing widespread unhappiness, which led to strikes, men 'jumping ship' - and the long overdue setting up of seamen's unions. The AISF fought tirelessly for an increase in sailors’ wages and a war bonus. Surat Alley was the AISF’s representative in London and campaigned on its behalf. In 1941 he published an article in the East London Advertiser to dispel the myth that after the 1940 settlement Lascars were adequately provided for. He concluded that the AISF had lobbied the Shipping Federation of Great Britain but the outcome was still disappointing, and the AISF renewed its efforts by negotiating with the Ministry for War Transport, arguing for fixed working hours, provisions for overtime, a welfare fund for aged retired sailors, compensation in the case of ill health and provisions for accommodation in port and on board, as well as canteens.

These attempts were resisted by the Shipping Federation. At the same time as Alley redoubled his efforts in Britain, he continued negotiating in India.

Due to the rivalry between the many Lascar unions, the AISF broke up in 1943. Surat Alley then went on to form the All-India Union of Seamen, centred in Great Britain in 1943, which was under the auspices of the International Transport Workers' Federation - later to become integrated into the Indian Seamen’s Union.

By the time the war ended in 1945, Lascar wages had increased by 500% to over £9.00 a month, but still less than half the wages paid to white seamen, who were earning, on average, between £20 and £24 per month.

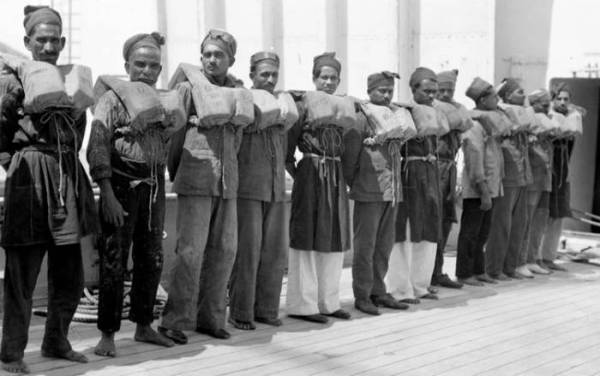

Crew inspection onboard P&O's Viceroy of India ~ Museum of London

Realising their worth to British shipping, Lascars saw an opportunity to force an improvement in their pay and conditions.

The Indian seamen's representative, Surat Ali, called for Indian seafarers to "get as much as possible out of British shipping companies now that Britain is at war."

The All-India Shipping Federation rightly sought compensation to dependents should Lascar sailors be killed, and a one rule for all was demanded - by which all employers were obliged to offer identical terms and conditions of employment.

In 1941, and again in 1943, when there were acute shortages of European seamen, recruiting teams were put to work in the West Indies and in Aden. Lascar seamen, previously protected from sailing on North Atlantic voyages in winter, were 'released' from this restriction now that the route was Britain's most important lifeline.

The Marine Department of the Board of Trade, hearing of the new terms to be offered to Lascar sailors, and anxious at the impact this might have on demands from white seamen, successfully asked the ship-owners to withdraw their offer. Confusion ensued, which only ended after two months - at which time wages were increased by the amount originally intended by the owners! In the interim, 310 Lascars had been jailed in the UK.

At the very moment the Board Of Trade was asking the owners to withdraw their offer of a 50 per cent increase, the Board of Trade was itself sanctioning a demand by the Indian crew of the Clan Macallister for an increase of 100 per cent!

On hearing this, the Lascar crew of the P&O liner Strathaird, refused to sail until they were offered the same terms. In both cases the ships were chartered to the government, and the BOT, needing to get the ships away, agreed the terms while insisting that the agreement made no reference to a 'war bonus'.

The chaos over pay continued unabated - in September the ship-owners awarded a further increase of 25 per cent - and when this proved insufficient to induce crews to put to sea, a further 25 per cent was given from 1st November, which again proved inadequate. On 2nd November seventy-six crew members of the Anchor Line's Britannia and Circassia were prosecuted and jailed for refusing to sail.

Their refusal was understandable given that just two weeks earlier, a pay increase of 100 per cent and a £10 cash bonus had been agreed with the Lascar crew of the British India Company's ship, Manela.

In mid-November 1939 an internal minute of the Ministry of Shipping noted the advice of an Ellerman Line marine superintendent, who said the increases were inadequate and that it would be necessary to go to 100 per cent. He was was also sceptical of the owners' view that prosecutions would deter any further actions. He was right on both counts. A month after the new pay rates had been announced crews were still refusing to sail - and were still being jailed!

In September 1940, Lascar wages were increased by 75 per cent on

pre-war rates, finally reaching 100 per cent in April 1942, and then were

doubled again only two months later to 200 per cent of pre-war rates in June.

Amongst civil servants there remained a recognition that Indian seamen were

being badly treated. A note attached to a minute of the Liner Division in the

Ministry of War Transport said that Indian wages were 'still very low compared

with the total wage earned by Chinese seamen, but I suppose we can do no more,

since the consensus of opinion among the experts seems to be against any larger

increases.'

Considering the insensitive attitude of the shipowners and the incompetence of the Board of Trade, it seems quite plausible that Lascars were obvious potential recruits to the Nazi cause. However, this was not the case. Lascar sailors remained true to the ethos of the British Empire.

Captain Hill, Senior Officer for all merchant seamen in Milag Nord POW camp in 1942 - and ex-master of the Mandasor, a ship with a Lascar crew, recorded an attempt to use the Indian prisoners to gather nuts in the autumn of 1942 - and how the Germans were thwarted by passive resistance. Hill claimed that the value of the nuts gathered was about one-tenth of the Lascar's wages. Furthermore, says Hill, when they returned to the camp at night they looked so dejected that they weren't searched but, 'Once down into their barracks they disgorged chickens, eggs, potatoes, and everything in high glee'.

Captain Hill also recounted the story of how a German plan to recruit the Lascars, and shift them elsewhere in Germany, failed when the Indians refused to enter the trucks, sat down in the road and dared the Germans to shoot them:

'The Indians returned in triumph at 5 p.m...... They got quite a rally from the rest of the camp as they came in. Captain Hill does not mention whether he stopped to wonder if such Schweikian activity - passive or nonviolent patterns of behaviour - had ever been deployed against the British; or that such open defiance might have required the same degree of moral strength as a readiness to face, unprotestingly, what must have often seemed like certain death in a lifeboat in mid-ocean.

Milag Nord was primarily for members of the merchant marine who had been captured aboard ships carrying allied ordnance or military-related supplies, together with several western European civilian internees.

Like many shipping companies, P&O set up a department that acted as a point of contact for families of captured sailors.

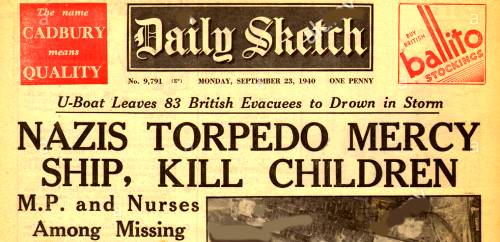

On 18th September 1940 a German U-boat U-48 torpedoed the Ellerman Line's City of Benares in the Atlantic. Seventy-seven British children, many as young as five or six, who had been sent as evacuees from Britain to Canada perished. In total, 260 of the 407 people on board were lost, including her master, Captain Landles Nicoll.

The tragedy stunned the British Empire. But less well known was the fate of the Indian crew manning the ship.

Of the 160 Lascars onboard, 101 were drowned or died in the shipwreck. Many of them have only ever been remembered by their forename, without a recorded date of birth and with the simple epithet ‘boy’ or by the basic description of their duty on board the ship: Soria the apprentice sailor; Sheikh Labu, a pantry boy, and Mubarak Ali, a baker, were among those who perished. Today, sadly, they remain little more than ghostly shadows in the archive.

Abbas Bhickoo, who was twenty-two years old, and from Sangameshwar, Ratnagiri, in present-day Maharashtra, was one of the Lascars who managed to scramble onto a lifeboat. With other survivors, he lay adrift for eight days until they were eventually picked up and taken to the west coast of Scotland. But Bhickoo died shortly afterwards, presumably from exposure. His grave still stands in Greenock in western Scotland.

Yousuf Choudhary, who as a child in Sylhet at the time, in present-day Bangladesh, remembered how the news of a seaman’s death would ripple through the community.

"As the news came, the dead seamen’s relatives and friends would gather and begin crying and shouting…soon the bad news spread from house to house, village to village. The people became nervous, worrying that they would be next in line for this shock. The British public never heard the cry of the seamen’s widows.’ Shivers rippled through seafaring communities whenever a torpedoed ship was reported: over the course of the war 6,600 Indian merchant seafarers would lose their lives, over a thousand would be badly wounded and over 1,200 would be taken as prisoners of war."

The Raj at War: A People’s History of India’s Second World War, Yasmin Khan, Bodley Head, 2015

Conditions for the merchant ships were very dangerous and thousands died. Indian records show that 6,600 seamen were killed during World War II, another 1,000 wounded and 1,200 taken prisoner, many of them Bengali seamen from Sylhet. However, it is likely that larger numbers died without being recorded.

From The London Gazette, 30th August, 1940.

The King has been pleased, upon the recommendation of the Minister of Shipping, to award Bronze Medals for Gallantry in Saving Life at sea to Neville Charles Eric Little, Third Officer; Valla Pema - Lascar Seaman, and Jairam Narron - Lascar Seaman, in the ss Barpeta, in recognition of their services in rescuing, on the 14th September, 1939, four members of the crew of an aircraft of the Royal Air Force in India, which had made a forced landing.

A boat had put off from the Barpeta to rescue the aircraft crew from the shore. The surf was very heavy and the boat was unable to pass through more than the first line of breakers, about three-quarters of a mile off the shore. It was necessary for Mr. Little, Valla Pema and Jairam Narron to swim to the shore and assist the rescued men through the water to the boat. There was a strong and dangerous tide and a risk of being incapacitated by the men who were rescued, three of whom were unable to swim.

Lascar sailors Mahomed Xyequb and Ana Mian, at Buckingham Palace, after receiving their British Empire Medals

The term Lascar is inextricably linked with the history of the Indian Ocean but has more than often been ignored in contemporary culture.

While the term was generally employed in a broad and inclusive sense to refer to all Indian seafarers, it specifically referred to men who

worked in the deck department. Amongst these Indian crews, there were a number of different ranks.

At the top of the deck department hierarchy were the Serangs - the native boatswain or chief of a Lascar manned ship. Reporting to the Chief Officer, the Serang

personally dealt with matters of recruitment and discipline on board ship - and was also responsible for paying his crew.

The tyranny of some Serangs became infamous in contemporary history, owing to their alleged demands for bribes in return for jobs. Serang Ali, aboard the Ibis, in

Amitav Ghosh’s absorbing masterpiece ‘Sea ofPoppies’, is one such outstanding figure.

Immediately below the Serang in the ship’s hierarchy were the two Tindals – Baloo-Tindal and Mamdoo-Tindal. The Cassab came next, and was in charge of the deck

stores – the ship’s rope, canvas and paint.

Then came the Bhandary, the crew's cook; and then, the Paniwallah who was in charge of the hoses on deck.

At the bottom of the ship’s Lascar hierarchy, was the lowly Topaz, engaged to undertake the dirtiest work on shipboard, such as cleaning the heads – the crew’s lavatories.

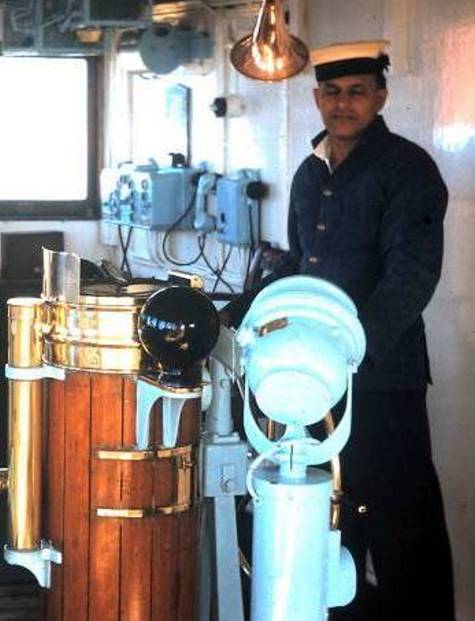

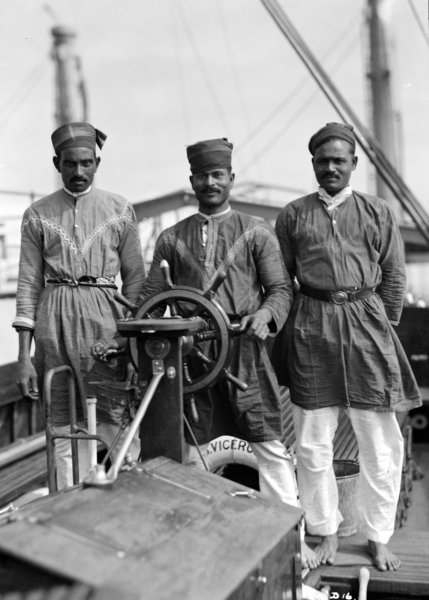

Senior men, separate from the ship’s routine daily chores were the three Sukunnis, Quartermasters – traditionally employed as helmsmen in vessels manned by

Lascars inthe East India Trade. Their place of work was the bridge, there to take the wheel, to steer the ship, working directly under the supervision of the ship’s

Master and Mates, from whom they deftly executed helm orders. “Starboard ten, ease to five; midships. Steady as she goes.” Helm orders were given in English,

and repeated back by the Sukunni, usually with ‘Sahib’ politely added as a suffix.

In port, the Sukunnis would keep watch on the gangway.

I recall one very elderly Sukunni who was growing more deaf by the day - making it difficult for him to understand helm orders unless they were shouted loudly. I resolved the problem by wiring him into the bridge Tannoy amplifier, by means of a headphone. Initially startled, he soon settled down once the sound level had been adjusted......

Lascar Serangs and Kalassis tended to be from the same region or were linked through kin groups. Crews recruited at Calcutta were composed of men from Sylhet,

Noakhali and Chittagong.

At Bombay, the bulk of deck crews consisted of men from Malabar in Madras.

The few written records surviving today suggest that Lascars often referred to each other as ‘kalassis’ - which simply means ‘sailor’.

Finding Lascar stories in historical records is extremely difficult. There are very few first-hand accounts written by Lascars - only bureaucratic, European references

in East India Company records, muster lists and logbooks, and the occasional parliamentary records.

In 1746, the articles for the East Indiaman ship Tryall recorded that the Lascar crew were paid a fixed monthly wage for the voyage from India to London. In addition, they were promised bounty money and maintenance, once their ship reached London, in order to tide them over while they waited for a return passage to their port of origin.

Needless to say, in practice, the Not-So-Honourable East India Company abandoned Lascars once they were in London, leaving them to their own miserable devices, frequently forcing the poor fellows to beg for meagre loose change. Eventually, the Merchant Shipping Act of 1823 made the Company legally responsible for the upkeep of their people while they were ashore in England.

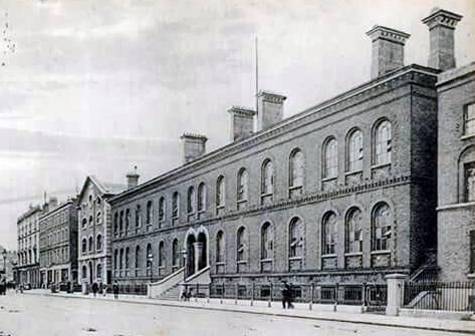

By 1856, Christian missionary societies had become concerned about the plight of Lascars, which led to the establishment of the Strangers’ Home for Asiatics, Africans and South Sea Islanders in West India Dock Road in the East End of London.

Lascars were in high demand as crew members on British ships. Steamships required larger crews and Lascars could be hired at a third of the cost of British seamen. An article in the Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register of June 1816, describes the character of Serangs as‘a class of men similar to the kidnappers of Holland and the crimps of England, but whom they far surpass in the arts they practise against those who unfortunately fall in their way…..’ In 1859, the lascar recruitment system did undergo slight modification. Before 1849 indigenous agents and intermediaries functioned under minimal regulation, this affected Britain’s ability to control the stable supply of Lascars keeping costs low and exerting effective control. After 1859, the hiring of Lascars was entrusted to registered brokers licensed by port authorities in Calcutta and Bombay. In reality, there was little change - as most of the Ghat Serangs quickly became brokers!

On 14th November 1882, The Whitby Shipping Trade Section in The Shields Daily Gazette proclaimed: ‘Intending passengers on steamships are warned of the danger of travelling on those ships that are manned by Lascars...passengers should understand that Lascars are carried by some firms solely on the score of cheapness.’

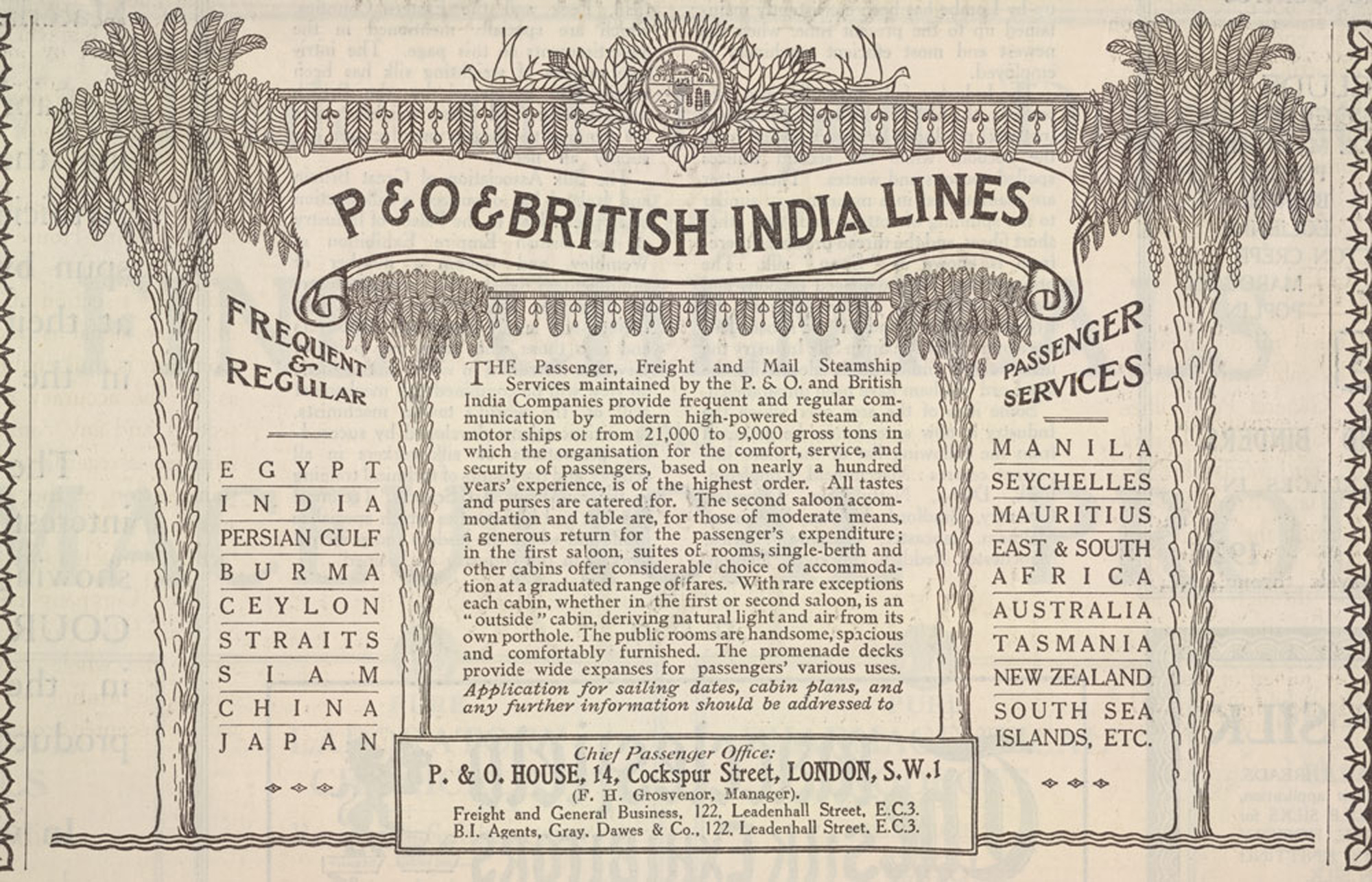

If proof of exploitation was needed, in 1897 the P&O paid its Lascars ’16 shillings to 18 shillings a month - whereas white labour was paid at the rate of£4 a month for seamen’. (Note: There were 20 shillings to every pound.) In 1899, Sir Thomas Sutherland MP, chairman of P&O, commented on the employment of Lascars by his company: ‘there are now 35,000 Lascars employed on British ships and that steamers for the tropics could not be well managed without them. The P&O Company employ about twice as many Lascars as British seamen and engage them upon an old family plan approved by the Indian authorities.’

But by the 20th century they had become all but invisible to European passengers, and, in the main, were left out of historical narratives of British maritime history.

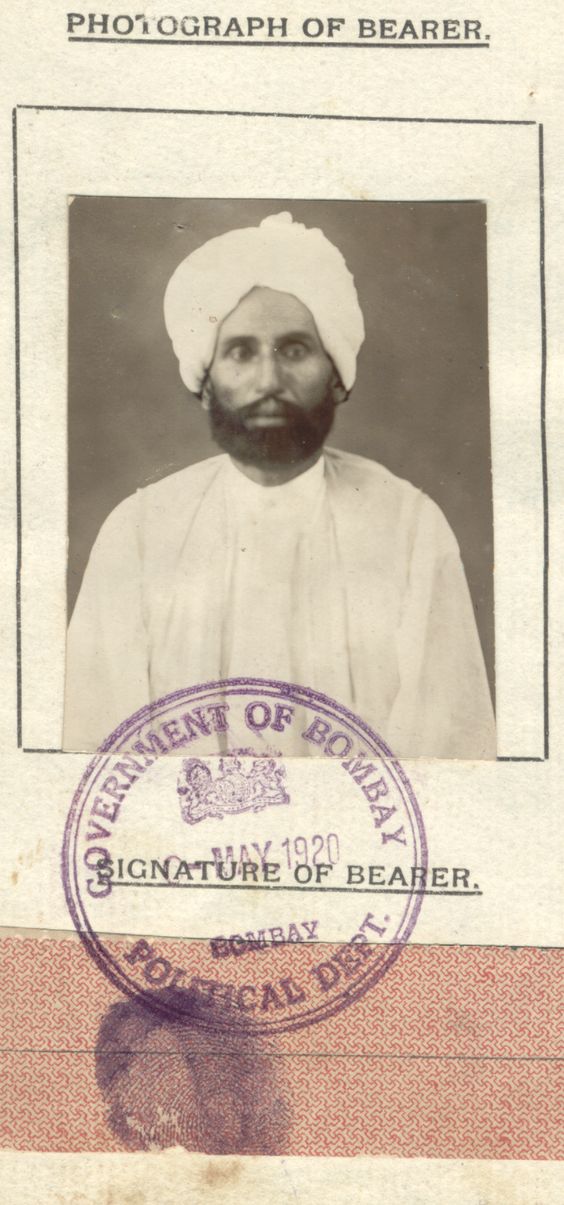

Lascars signed separate ship’s articles to those of British sailors. Lascar Articles kept Lascars in a subordinate position. The stipulations of Lascar Articles reflect how Lascars were exploited. Employers such as P&O paid Lascars between one third to one-fifth of white seamen - while accommodating them in comparatively squalid living quarters.

Serang Habiboola Ahamdeen

Very few could write their names and used a thumbprint to 'sign on'.

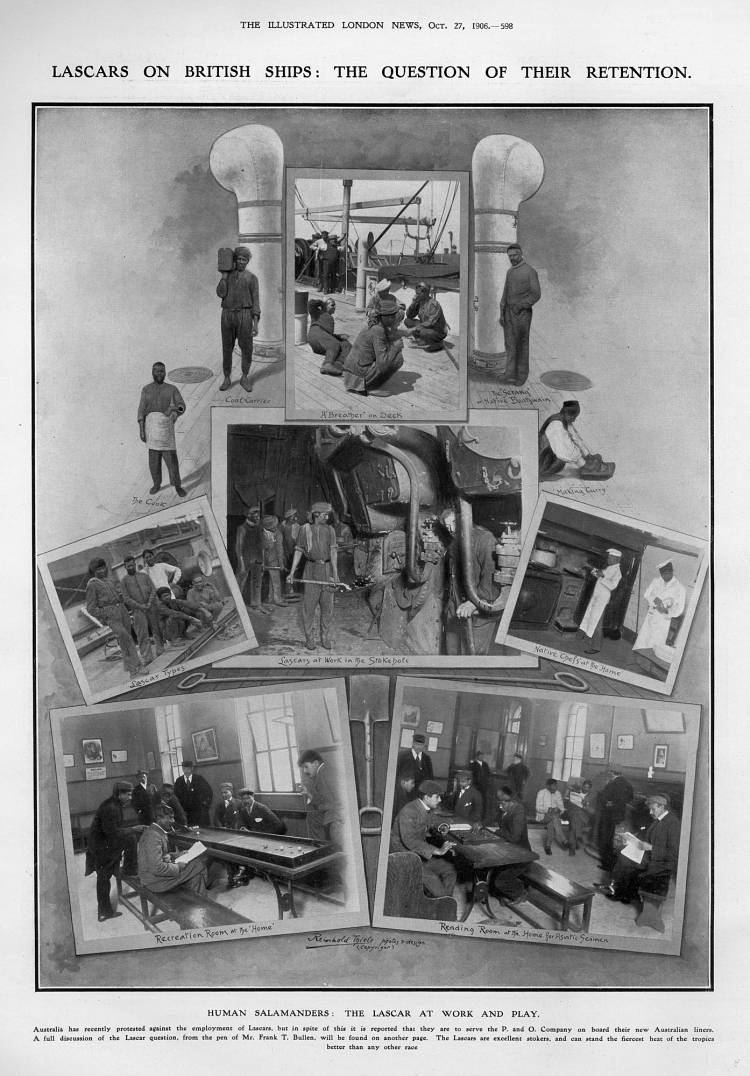

A 1906 collage of Lascars on board ship and on shore at the Home for Asiatic Seamen.

From The Illustrated London News as held by The Mary Evans Picture Library.

The Board of Trade stated that they "have no control over the rates of wages at which Lascar crews are engaged for service in British ships. Lascars are normally engaged at ports in India on a form of agreement prescribed by the Government of India under the Indian Merchant Shipping Acts.

Historically, Lascars were paid less than their European counterparts. According to a 1910 Parliamentary Report, they received only 8-9 shillings per week. They were often described as ‘docile’ and ‘manageable’ and unlike white sailors they did not partake of alcohol, were not unionised, so considered ‘trouble free’.

Placed on the lowest rung of the imperial hierarchy of sailors, Lascars were discriminated against, paid less, treated poorly on board ship - and worked in difficult roles on steam-powered liners.....

British Seamen's wages compared with Lascars

From the report of the Committee appointed by the Board of Trade to inquire into certain questions affecting the Mercantile Marine 1903.

European Rating’s Monthly Wages – v - Native Rating Wages

Boatswain £5 - £6 10s Serang £2 6s

Boatswains Mate £ 5 Tindal £2 1s

Quartermaster £4 10s Seacunny £1 13s

Able Seaman £4 Lascar £1-3s - £1 13s

European Crew Cook £4 Bhandary £1 6s

Paniwalla £1 14s

Topass £1 1s

The rates of pay for Lascar crews varied according to the port at which the men were engaged. The following are the rates for crews engaged at Calcutta. The sterling equivalent is calculated at the rate of exchange on the 3rd March 192

Rating Rupees / Month £s / Month

Serang 60 £4 - 1 - 3

1st Tindal 37 £2 - 10-1

2nd Tindal 30 £2 - 0 - 8

Cassab 30 £2 - 0 - 8

Kalassi 25 £1 -13 - 10

Chokra Kalassi (Boy) 12 16 - 3

Bhandary 25 £1 - 13 - 10

Topass 22 £1 - 9 - 10

Scale of Wages 1937

Glossary

Lascar - A general term used to refer to all Indian seafarers, from the Persian-Urdu word lashkar.

Serang - Lascar Chief Petty Officer / Boatswain - chief of a Lascar crew.

Tindal - Lascar Petty Officer / Boatswain's Mate

Kalassi - Lascar Sailor

Chokra Kalassi - Boy Sailor

Bhandary - Lascar Crew’s Cook.

Cassab - Kalassi in charge of the deck stores.

Paniwallah - Waterman / Crew member in charge of hoses on deck

Seacunny - Native Quartermaster / Helmsman

Topass - Man engaged to do the dirtiest work on shipboard - such as cleaning the lavatories.

Ship’s Articles - the set of documents that constitute the contract between the Seamen and the Captain (Master) of a vessel. They are presented to port authorities and foreign consular officials in order to establish the bona fides of a ship.

'As all the men, while the vessels are in London, are below at the same time either taking their meals or sleeping, it will be seen how over - crowded and unhealthy the spaces are, and I may add that I would not enter them to make a proper inspection... owing to the smell and filth.'

Steel-framed bunks, six to twelve men to a cabin, located as far aft on the ship as possible, with basic latrines and a galley to port and starboard - Indian sailors accommodated on the port side and Pakistani engine room crew to starboard, was generally the order of the day in cargo ships. Commentators argued that Indian seafarers' accommodation on British ships had serious consequences for the men. The impact on their health was particularly highlighted by the investigations of Fleet Surgeon W.E. Home, who compared the death rates of European and Lascar seafarers for the period 1913 to 1914. He found that Lascar seafarers had a higher death rate of 5.4 per 1000 compared to 3.5 per 1000 for Europeans. Home argued that this illustrated the need for greater cubic space for Lascars.

Home's investigations also revealed that Indian seafarers' death rates from "infectious diseases" such as from pneumonia and tuberculosis were higher than European seafarers. This confirmed his fear that smaller crew spaces had a detrimental impact on the health of the men. The close, intimate living conditions of shipboard life facilitated the spread of infectious diseases.

In his official report, the accommodation or living space for crews, was described with shock and horror by Fleet-Surgeon W.E. Home, who wrote in 1913 of how "the amazement, and gradually, the horror, at the sight of what we then encountered are sentiments that remained fresh, at the end of five years experience sufficiently overwhelming to blot out most things". The accommodation of Indian seafarers is evidenced in the following description from a Board of Trade Surveyor. The Surveyor noted that 'As all the men, while the vessels are in London, are below at the same time either taking their meals or sleeping, it will be seen how over - crowded and unhealthy the spaces are, and I may add that I would not enter them to make a proper inspection... owing to the smell and filth.

Lascar accommodation on board ship

From The President of The Board of Trade:

The P. and O. steamers Sumatra, Arcadia, and Caledonia are British, registered vessels. The Sumatra is to carry 65, the Arcadia 132, and the Caledonia 157 Lascars. The space allotted to each Lascar on the Sumatra is rather over 71 cubic feet, on the Arcadia 70.6 cubic feet, and on the Caledonia 79 cubic feet. There is thus, in the first two cases, rather less, and in the third, somewhat more, space than is required under the Imperial Act. Under section 210 of the Merchant Shipping Act, 1894, each seaman shall have appropriated for use a space of not less than 72 cubic feet and of not less than 12 superficial feet. For each contravention of this requirement the owner of the ship is liable to a fine not exceeding £20. If this were the only section operating the law "would be clear, but it is not. Under the Indian Merchant Shipping Acts, only six superficial and 36 cubic feet are required. Under section 123 of the English Act of 1894, the master or owner of any ship may enter into an agreement with Lascars, and the unrepealed provisions of an old Act of the 4th Year of King George IV, specially empowering the Indian Government to make regulations with respect to the accommodation of Lascars, are safeguarded. The effect of these various enactments is, that it is by no means clear whether the direct obligation in respect to crew space of the English Act or the Indian Acts obtains in regard to Lascars The exact effect of these provisions has been referred for the advice, of the Law Officers of the Crown, and the Board of Trade are in communication with the Indian Government through the India Office with regard to the provisions of their law.

"Serang and Tindals made us work like Gadhas (donkeys) without sufficient food. Neither would the Serang ask the steward for our full ration, and as he was well supplied he did not care about us, neither would he speak to the Captain about giving us some money, but he as well as one or two of his relatives had all they wanted."

Scale of Lascar provisions in 1937

Lascar food rations were considerably cheaper, and the low cost of Lascar food meant the employers saved money.

Lascar provisions cost less than those required to feed a British sailor. The Greenock telegraph of 1893 provides an excellent example of Lascar provisions on a ship. “the messing of the crews includes saltfish, rice and pulses with ghi and sugar, vegetables and condiments necessary for curry cooked in a galley set apart for their use. Tea which is much prized and often taken three times a day is also given.’

Lascar rations were often substandard in taste and appearance,

‘The only diet which the Lascars had during the last three months was rice and fish. The rice was of the most inferior description, and the fish was only fit to be thrown on a dunghill being rotten full of vermin and stinking most horribly.’

It was not only what Lascars ate that was distinctive but also how they ate.

‘They squatted in a circle on the deck, eating their frugal midday meal.

In the centre stood a large copper dish containing rice - nice light and cheap food but much neglected by the Britisher.’

The Lascars dispensed with plates, nor did they need spoons.

With the thumb and two first fingers of the right hand.

It was a simple way of making dinner, but they seemed to enjoy it.’

The length of a Lascar's voyage

Two year labour contracts formed the basis of Lascar articles, whereas British seamen could sign on for one year or less.

The length of voyage specified in articles was a way of limiting Lascar movement. Ship's Articles also mandated the transfer of Lascars from one ship

to another. For example, in 1897 thirty Lascars signed an agreement to “work the Janet Mitchell to England and to work that vessel or any other

owned by me back to India at certain stipulated wages.” Another limiting aspect of Lascar movement was that officially they could only discharge at

ports in India, but newspaper advertisements show how the practice was ignored. For example, in 1904 an advertisement asked for Lascars to crew a

steamer from London proceeding shortly to India. This example demonstrates Lascars must have discharged and reengaged in England. For Lascars,

the voyage length was problematic because they were not paid until the end of the voyage. As a result, it was common for Lascars to enter into wage

disputes. In 1855 a group of Lascars had shipped from Calcutta to Bristol but were not paid, the captain of the ship had said it was agreed he would

pay the Lascars on their return to India as passengers: the Lascars refused. Although Lascars signed ships articles of their own accord and in a sense

were free labour controlling influences such as the length of voyage and withholding of wages made their employment a much more restrictive form of

labour similar to that of indentured labourers.

Lascars and the Trade Unions

By 1919, the British merchant fleet relied on a significant number of Lascars......

Lascars were recruited in ports abroad on lower wages than their British counterparts.......

In Britain, Trade union resentment simmered.........

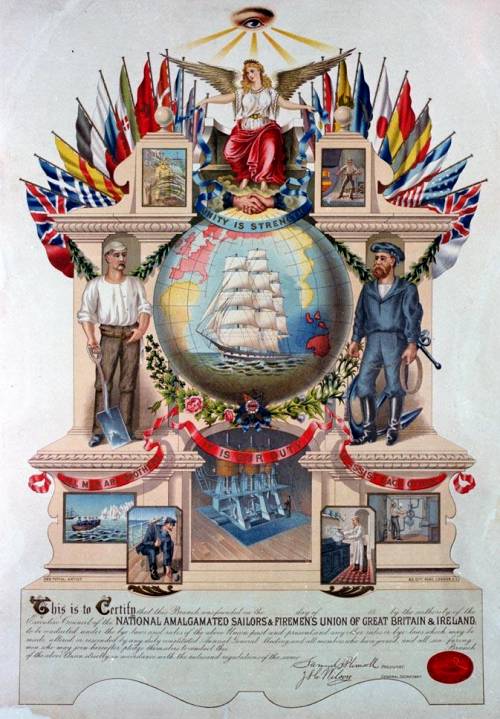

Through The Seaman, the journal of the National Sailors’ and Firemen's Union (NSFU), a campaign to keep “colonial” sailors off British ships was launched, and in September 1919, the Trades Union Congress passed a resolution demanding “immediate steps be taken to abolish all underpaid Asiatic labour in the Mercantile Marine, and that preference of employment be given, first to white, then to British coloured, in preference to Chinamen”.

Great Britain's small immigrant communities made convenient scapegoats.

In Poplar, East London, a rumour that a coloured sailor and his British wife got housing previously refused to a recently demobbed man, sparked a riot.

Race riots broke out in Glasgow, enthusiastically supported by trade unionists……

The British press termed them ‘race riots’ and authorities attributed the violence to black and white seamen competing for

jobs. Who was and was not defined as British was becoming more publicly about race and in 1925 the British government passed the Special Restriction (Coloured Alien Seamen) Order. The order stated that ‘coloured’ seamen in Britain without documentary proof of their British status must register as ‘aliens’. Police were to apprehend ‘coloured’ men disembarking from ships and report them if they failed to show their documentation. War-era Certificates of Nationality and Mercantile Marine books were often not enough for the police. The Indian and Colonial Office received numerous complaints from colonial seamen and their families. Many black and Asian seamen from British colonies were deported.

There was a complicated relationship between ideologies and material interests in discourse about the role of Lascar crews, with shipping companies and captains tending to support employment of Lascars, and racial ideologues, British trade unionists and the Board of Trade opposing - or at least striving to limit their inclusion in the labour force.

Representations of the British sailor and the Lascar tended to be interdependent. The social agency of Lascars shaped the way they were represented. An intense battle over the role of Lascars at the end of the nineteenth century and the start of the twentieth tended to produce a dominantly anti-Lascar ideology. However, this did not actually result in an effective reduction in the role of the Indian seafarers in the British Merchant Navy. Changes in racial ideology and the political conjuncture led to a shift in policy towards Indian seamen in the 1940s. Soon, the coming of Indian independence gradually saw the decades of Lascar employment aboard British ships approaching an end.

Lascar crew painting P&O ss Iberia's funnel - Photo: Fremantle Port Authority.

But it was not until the last traditional Indian Deck Crew was discharged from P&O's flagship, Canberra in 1986, that the era finally came to an end.

By then, the general decline in UK merchant shipping, and the heavily unionised and expensive British merchant seamen, had resulted in very few British sailors finding employed aboard British merchant ships. The one exception being the Royal Fleet Auxiliary's civilian manned logistic support ships, operating in support of the Royal Navy.

The majority of shipping companies treated Lascars appallingly - simply because they could get away with it. For their part, the Lascars had a reputation for being ‘trouble free’ - which was shamefully exploited. I would imagine that contemporary racism played a part in all of this as well. Before we dismiss the Lascars as submissive, however, here is an example of them standing up en masse and, while it was ultimately unsuccessful, it demonstrated that they were more than capable of sticking up for themselves.

In early July 1884 four Lascars sailors were brought before Mr Philips at West Ham Police court charged with being the ringleaders of a mutiny on a British vessel docked in London. The formal charge was that they had refused to obey their captain, William Turner of the Duke of Buckingham, a steamer operated by the Ducal Line Company. The ship’s crew was made up of 45 seaman, all Lascars who had signed articles in January 1884 to serve on the Hall Line’s steamer Speke Hall, for a year. The ship docked at Liverpool for repairs and the owners decided to transfer the men to another ship. When she reached London and the crew discovered that this ship was headed for India via Australia they protested. Some argued that their contract - their 'articles' - were with the Hall Line and not the Ducal Line. Others complained that the journey would be too long, and they would be beyond their 12 months of employment. 18 of the 45 men refused to work and four were identified as ringleaders and arrested, hence the court appearance in West Ham. The four were: ‘Amow Akoob a Serang, Manged Akoob, a Tindal, and Fukeera Akoob and Adam Hussein, Lascars’.

Perhaps unsurprisingly the English magistrate wasn’t about to get deeply involved in an industrial dispute. He pointed out to the men that at the current time they were under contract and warned them that they were liable to ‘penalties’ if they and they rest of the crew continued to refuse to work.

In the end the four men decided that they’d made their point and had little to gain by continuing their protest.

They agreed to return to work and were discharged.

A group of Lascars, with their bushy looks and swarthy skins, contrasts strangely with the solitary Chinaman who leans thoughtfully against the wall, his pigtail over his shoulder.......

For many Lascars, living in Britain meant a life of destitution and poverty. The lack of resources available to Lascars made it difficult for them to enjoy their lives. Many chose the company of other Lascars and lived in poverty in areas such as the oriental quarter of London. By the mid-1850s Lascars were beginning to attract the attention of missionary societies and by 1857 homes such as the Strangers Home for Asiatics were providing accommodation, food, access to the Christian faith and the ability to get home - or at least back to sea.

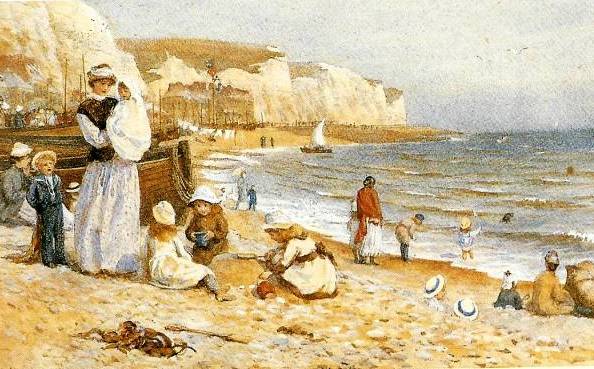

'The Governess and the Ayah on the Beach' by Helen Allingham,

For centuries, Indian women and girls were hired by wealthy British families to care for their children as nursemaids and nannies, called Ayahs. By the late nineteenth century Ayahs were a key feature in British households in India. They were also a regular sight on board ships, where they were employed to care for and entertain their charges during long sea journeys, telling them stories, playing games and attending to their every need - but often sleeping on deck, on a rolled up mattress outside their employer's cabin. Like the majority of Lascar sailors, once their ship reached Britain, they were paid off - and made to find their own way home - often with only a few pounds in their pockets.

There were thousands of Ayahs who made the sometimes dangerous journey to and from Britain, helping to build the British Empire from the bottom up.

The appalling working conditions of Lascar sailors led some to jump ship in Britain. This community of destitute Lascars, Ayahs and former servants of the British Raj, had no option but to find alternative ways of earning a living. Some sold Indian spices, others found odd jobs, worked as street herbalists, or toiled as casual labourers - in a sometimes harsh climate, far from home..

They were among the earliest Asian working class settlers in Britain.

For the Lascars who settled in British ports, life was initially very hard. The majority were single men far from home, unemployed for long periods and in extreme poverty. Most lived in lodging houses. At first these were run by the East India Company but later, after the British government took over control of India in 1858, many were run by people from their own communities. The government, under pressure from the Seamen’s Union and because of negative racial attitudes, passed laws intended to make it hard for them to stay. In spite of the difficulties, many immigrants survived and went on to put down roots. Some married local women and started Britain's first modern, working-class multicultural communities. Others moved from work on the ships to setting up businesses such as cafes, lodging houses, shops and - in the case of the Bengalis and Gujaratis - built up Britain’s first Muslim communities in the port areas of Cardiff, Liverpool, Hull, London and South Shields.

Official Registers of the period describe marriages between local women and Lascars. Some with less than satisfactory outcomes. For example, one of the Marshalsea Prison's Lascars was arrested for violence against a Catherine Brownlow who had frittered away his money and then married another Lascar.

Despite unpleasant prejudice from some quarters of British society, there were no laws prohibiting intermarriage, and a mixed community grew up in London’s docklands, Wapping and Shoreditch.

In general the British authorities often publicly supported Lascars, given the egregious nature of some of the abuses against them - but at the same time hypocritically implemented regulations which were highly detrimental for them. For instance by the end of the 17th century although the Admiralty in theory paid their passage back to India, they would in fact charge the cost, which could range from £4 to £6 back to the owner of the ship. This in turn led to many captains forcing their ‘passengers’ to work in horrendous conditions during their passage home.

In 1855, the British Mercantile Marine took on 10,000-12,000 Lascars every year - half of whom were brought to the UK and dumped here to fend for themselves. In 1850, 40 'sons of India' were found dead of cold and hunger in London alone, and by 1857, the missionary, Joseph Salter's 'Stranger's Home for Asiatics, Africans and South Sea Islanders' was opened in Limehouse, East London. In 1867, Salter discovered and offered help to small numbers of Lascars in Birmingham, Brighton, Southampton, Manchester, Liverpool, Edinburgh, Sunderland, Durham, Glasgow, Hull, Stirling, Leith, Bath and the Isle of Wight.