"ALL WELL and SAFE - PLEASE DON'T WORRY"

Telegram postmarked Malaya, dated 8 January 1942, signed by Lena Clarke

Between the wars......

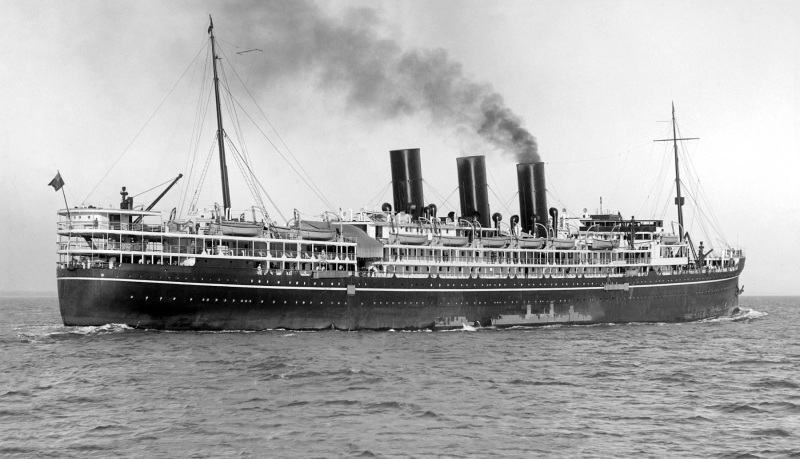

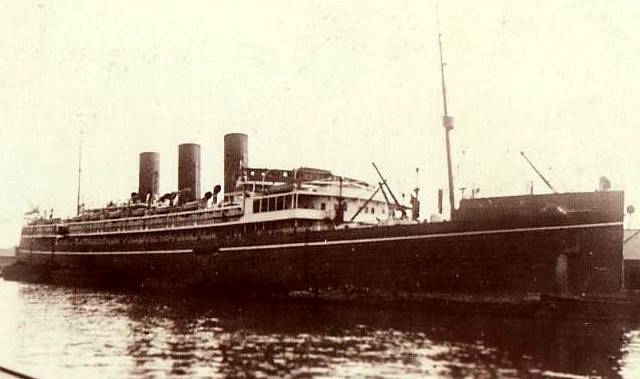

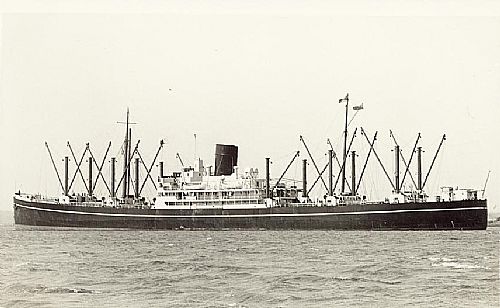

At the end of the Great War, P&O had two unfinished passenger ships, Naldera and Narkunda, which had fallen victim to government indecision concerning their projected use. It was said that they had been frequently reconfigured by government naval architects - for every possible role - apart from that of submarines! Fortunately, in 1919, they were soon taken in hand by the P&O board and restored to their true role, as passenger ships operating on the lucrative Australian mail and passenger run. Fitted out in a somewhat dated style, and still with her original coal-fired boilers, Narkunda commenced Company service in April 1920, with a round trip voyage to Bombay. In July, she made her first voyage to Australia, where she was well received by a war weary populace. Unlike her sister, Naldera, Narkunda was converted to oil-fired boilers in 1927, which substantially extended her career.

It's War again.....

A very fine watercolour of Narkunda, signed John Allcot.

"At

the outbreak of war I was 18 years old and had been in England since I was

eleven attending school. In November 1939 I set off from Southampton to rejoin

my family in Shanghai, China. My father had been in the import-export business

and at this time was chairman of the Shanghai water works and other utilities

companies. I sailed on the P and O liner SS Narkunda. It was a fast ship and

quicker than the normal convoys so we travelled alone. It was a terrible journey

at first. There was a complete black-out at night, depth charges were fired from

the stern to ward off German submarines and we had constant lifeboat drills. I

had a very uncomfortable time sharing a cabin with two others right above the

propeller which was noisy. We had to sleep with our bulky lifejackets on and

evacuate through the Indian sailors quarters. It was a hair-raising time, but

improved once we reached the Mediterranean. The lights came back on and it

almost became a normal voyage, since Italy had not yet joined the war. We called

at the usual ports: Port Said, Aden, Bombay, Colombo, Penang and made our way to

Hong Kong. My mother and elder sister met me in Hong Kong and after a brief stay

we left for Shanghai. It was my first time back in a long while and it all felt

very strange and I found it difficult to fit in. I felt rather gauche amongst

the young set and their parties. Many of the young men were trying to join the

armed forces and get to Britain or India, but some, including my future husband,

were told to stay at their posts. At this time Japan was not considered a direct

threat although rumours abounded and by the summer of 1941 it was obvious the

situation was getting worse. People began leaving for Australia and Canada, but

few for England. In late 1941 my father was told off-the-record by the British

Consul that he should leave as quickly as possible. He booked passage for us,

but the earliest available was in mid-December. The Japanese attacked Pearl

Harbour on 7 December, declared war on Britain at the same time and invaded

China. We found ourselves trapped."

By:

Heather Burch ~

Lunghwa internment

camp

"The ship became filled to capacity. As I watched the baggage being swung in cradles from the wharf to the forward hold, the labels showed Bombay, Singapore and Hong Kong. The passengers included rubber planters and Government officials returning from leave, and wives and children going back to join their husbands and fathers in Malaya or India. The smokeroom was taken over by sixty Marines, whilst the Second Class section accommodated Dutch youths who were going to Java to join the Dutch Navy, and a few Sergeant Pilots of the RAF. Loading continued all day. At night the German bombers came over. We were not allowed off the ship, and the weather was bad, so we stayed in the lounge whilst the anti-aircraft guns rattled overhead and the pulsating roar of the bombers filled the air. No bombs seemed to drop near to our ship, and by bedtime all was quiet. The Narkunda did not sail until the third day, when she was pulled out by tugs to the harbour mouth to take up position in the estuary. We saw a French Hospital ship and an assortment of cargo vessels of many nationalities, with destroyers moving around assembling the convoy. Once in position we anchored and waited, from two o'clock until dusk. At last the Narkunda sailed alone, leaving the convoy behind. Not quite alone. For the first twenty-four hours the ship was visited by Sunderlands and Spitfires, until at last we were on the high seas, sailing northwest. The November weather became colder and the seas worsened as we headed for mid-Atlantic. The feeling of loneliness in a crowd of strangers was oppressive. Bad weather kept us inside for the most part. Miserable groups filled the lounge, reading, knitting, smoking in the stifling atmosphere, and playing Bridge. Apprehension mingled with boredom and tobacco smoke - what on earth was I doing there? Then at last came a little relief, as piano music filled the air. The young Director of Music for Singapore, a man called Williams, went to the grand piano and played a waltz. A ballad followed. Passengers murmured approval, a few applauded, and the ice thawed a little. The recitals became a popular evening feature. After dinner one evening a fellow diner suggested a walk on deck, as the weather had improved. As we paused to let our eyes become accustomed to the darkness, he asked me if this was my first trip. It was probably obvious to everyone that it was. We began to pace the deck, and talked about our destinations and what lay ahead. He was a Scot named Young, and he filled me in with a mass of advice and information on customs, ways of living, social life, dress - many things still to be discovered. The walk on deck became a regular feature of life on board, and Young introduced me to other passengers as the long days went by. As the ship headed south down mid-Atlantic the weather improved, and we were able to play deck games. Radio silence isolated us from news of the War, so that we were in a little world of our own. There was the daily log to read, and the sweep to guess the mileage covered, and a strange game at night called Housey Housey, which seemed to me too silly to bother with. Years later that game emerged in converted cinemas with the name of Bingo. On the eleventh day a small cargo vessel was seen riding high in the water, flashing signals to us. We were told that the captain of the St. Marie II had been dangerously ill for three days, with a temperature of 104, and that the cargo ship had no doctor aboard. The Narkunda hove to and lowered a boat in the heavy sea. The boat was carried away on the first attempt, and we had to chase after it. Then the crew of the cargo boat lowered the sick man on a stretcher into their own lifeboat, and pulled across to our port side. The blanket which covered him was removed, and he lay in his pyjamas on the stretcher, exposed to the winter sea air, panting for breath, his face the ghastly pallor of death. He was strapped into a canvas bag and hauled aboard. His few belongings followed him to the ship's deck. The crew pulled away. The captain of the St. Marie II died overnight, and was buried at sea the following morning. Fitting, I suppose, for a mariner in Wartime, when Britain's lifelines were in peril. Flying fish were seen for the first time one Sunday in November. They were leaping from the water and gliding from crest to crest of the light sea swell, tipping the brine with tiny flecks of spray and flying for incredible distances like gleaming swallows. Two days later the shores of Africa came into view, at first a dim grey line in the early morning light, then changing to a palm-clad outline as the ship neared the coast. We steamed into the harbour of Freetown, Sierra Leone, about 8º north of the Equator. The ship steamed gently past slender canoes whose occupants waved spear-shaped paddles in salute, and anchored opposite the oil tanks. One side of the wide natural harbour was flat and swampy, with palms and low vegetation. The other shore was fringed with hills, Government buildings and quarters lining the slopes, and a lighthouse on the headland. Now one of the bits of official advice given to me related to Malaria. The effect of Malaria was known to me, because a Colne cricketer was a sufferer. My personal effects therefore contained a bottle of quinine tablets. Although we were not allowed to leave the ship, and there was a considerable distance between us and the swamps, caution overcame valour, and I took a tablet. Mosquitoes were not going to get me so early in my adventure abroad. That is how green I was." From: Voyage to Penang and a New Life, by Samuel Bailey, Assistant Engineer in the Colonial Service

By 1940, the worsening situation in France caused Narkunda, homeward bound from Australia, to cancel her scheduled call at Marseilles to land passengers. In April 1941, she was requisitioned by the Admiralty and quickly converted for her new role: as a troopship

April 1941 found her in company with the ill-fated battle-cruiser Repulse.

The battle cruiser HMS Repulse by Jaap Pluimgraaff

2nd April – In approximate position 35-50N, 12W the destroyers HIGHLANDER, VELOX and WRESTLER from Gibraltar, RVed with REPULSE, FURIOUS, and troopship SS NARKUNDA 16632grt to escort them into Gibraltar.

3rd - REPULSE, FURIOUS, and troopship SS NARKUNDA escorted by destroyers HIGHLANDER, VELOX and WRESTLER arrived at Gibraltar.

4th – At 0800 hours REPULSE, aircraft carrier ARGUS, and troopship SS NARKUNDA escorted by destroyers HIGHLANDER, FURY and VELOX sailed from Gibraltar for UK.

(This deployment was requested by the CinC Home Fleet)

(At 2311/5/4/41 the Admiralty signalled the CinC Force H that there are indications that the German battlecruisers may leave Brest during the night of 6/4/41. This because on the 5 /4/41GNEISENAU had been moved out of dry dock due to a UXB and moored in mid stream. Early on 6/4/4l, 4Beauforts of 22 Squadron of RAF Coastal Command carried out a torpedo attack on GNEISENAU and aircraft X/22 achieved a hit on the starboard side aft causing considerable damage. On 7/4/41 GNEISENAU was moved back into dry dock)

5th – At 0730 hours FURIOUS escorted by destroyers FAULKNOR and FORTUNE joined the REPULSE group. Following which FAULKNOR detached to re-join Force H.

6th – At 0011 hours the Admiralty signalled the

REPULSE to continue in execution of present orders. Further instructions will

follow.

At 1529 hours the Admiralty signalled the CinC Home Fleet, who was in position

45-26N, 16-06W, to release the cruiser LONDON to RV with REPULSE and take over

the escort of ARGUS, FURIOUS and NARKUNDA. The LONDON was detached at 1830

hours.

7th – At1100 hours in position 41N, 22-30W the cruiser

LONDON joined and took over the escort.

Following which REPULSE and destroyers HIGHLANDER, FURY and FORTUNE detached to

proceed to position 45N, 21W to RV with the battleship QUEEN ELIZABETH.

December 1941 found her in a troop reinforcement convoy, bound for Singapore....

Narkunda's master was Captain M G Draper and her medical officer, Doctor B Wallace.

The Japanese 25th Army invaded Malaya from Indochina, moving into northern Malaya and Thailand by amphibious assault on 8th December 1941, one day after the attack on Pearl Harbour, meant to deter the US from intervening in Southeast Asia.

As early as 1920, British Imperial defence strategy had envisaged deploying a naval task group to Singapore should Far Eastern possessions or interests be threatened. Designated Force Z, it was sent to intercept Japanese landings in Malaya, and consisted of the most recently constructed capital ship in the British Navy, the battleship HMS Prince of Wales, accompanied by the battle cruiser Repulse, and four destroyers, all under the command of Admiral Sir Tom Phillips. The aircraft carrier HMS Indomitable was to have been part of the force, but was undergoing repairs after running aground near Jamaica. With the force lacking an aircraft carrier, Admiral Phillips anticipated air cover from the Royal Air Force flying out of Singapore and sailed from there on December 8th—too late to disrupt Japanese landings on the east coast of the Malay Peninsula that same day.

HMS Prince of Wales and Repulse were sunk by Japanese air attack on 10 December 1941. Without air cover, they had not stood a chance ........

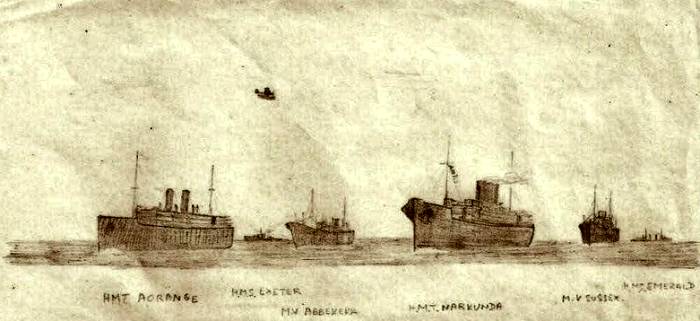

P&O's ss Narkunda formed part of a troop reinforcement convoy of four ships, hurriedly assembled at Durban. They carried the 53rd Infantry Brigade Group - part of the British Army's 18th Division; 232 Squadron RAF; 51 crated Hurricane fighter aircraft; the 6th Heavy and 35th Light Anti Aircraft Regiments, and the 85th Anti Tank Regiment and 24 Hurricane pilots.

Narkunda embarked 1,773 troops of the 6th Heavy Anti-Aircraft and the 35th Light Anti-Aircraft regiments of the Royal Artillery.

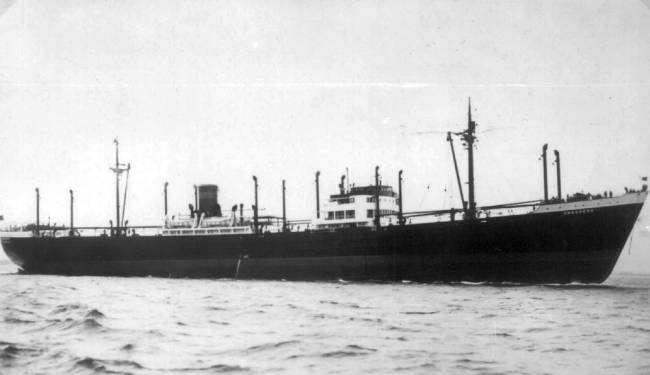

The Union Steamship Company of New Zealand's MS Aorangi, of 17,491 tons, with 2,194 troops embarked.

The Federal Steam Navigation Company's MV Sussex, of 11,063 tons, carried crated Hurricane fighters, 3.7 inch AA guns and 14 troops.

The Dutch Verenigde Nederlandse Scheepvaartmaatschappij MS Abbekerk , the smallest ship in the convoy at 7,906 tons, carried ammunition and 16 troops. See http://www.msabbekerk.nl/ for a well documented history of this brave ship.

Convoy DM.01 from Durban to Singapore. Drawing by Lt Geofrey North, 35th LAA Regiment, Gunner aboard Abbekerk.

I really did enjoy the whole trip and was sorry to reach Singapore, which we did, on 13th January 1942."

Bombardier Nevil C.C. Benham, 35th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment Royal Artillery.

Leaving Durban on 24th December 1941, Singapore Reinforcement Convoy DM.01 set sail with one naval escort, HMS Exeter, and after several days a sea, in light of intelligence reports, was ordered to split in two and change course. With the Far East situation deteriorating rapidly and the invading Japanese Imperial army already ashore on the Malay coast and heading south, Narkunda and Abbekerk received orders to immediately proceed to Singapore. Approaching the island, heavy monsoon rains masked their approach, while Allied artillery fire downed ten enemy aircraft on 12th December. The convoy finally reached Keppel Harbour on the 13th January 1942.

The Narkunda had a Lascar crew and this was even reflected in the quality of the food. Meals were served on long tables between decks, there being no separate dining room from living quarters. One advantage we did enjoy was being allowed to sleep on deck. Hammocks were slung in every conceivable place and even rolled out on the decks. I recall one occasion when I slung my hammock a little too near the side and when the ship rolled in a rough sea off the Cape, the water appeared to be immediately below me! I need hardly say that I made a hurried move to a safer place! Some days after leaving Durban the convoy divided, one part going to Bombay and the other with the Narkunda to the Maldives Island which are south of Ceylon. This was truly a beautiful sight, just like a scene from a film taken in the South Seas. We were not allowed ashore because there was only a wireless station and the stop was for refuelling only. Although I might have been bored at times, I really did enjoy the whole trip and was sorry to reach Singapore, which we did, on 13th January 1942." Bombardier Nevil C.C. Benham, 35th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment Royal Artillery.

"By the time the convoy arrived in Singapore the harbour was under constant attack. The Hurricanes and guns were quickly unloaded but harbour workers simply refused to unload the ammunition. The crew then unloaded part of it but after a couple of days no empty barges came anymore. By that time there were no bombers left in Singapore for the heavy bombs Abbekerk was carrying. Abbekerk then sailed alone to Oosthaven were she helped to destroy (sink) barges and unloaded some more cargo. But she also had to unload all her bofors guns and the English troops that manned it." By Peter Kirk.

"I can’t say we were welcomed to Singapore, because it was the other way round. The Japs chased us from the start, as we steamed into harbour planes could be heard overhead. I was standing on the front part of the promenade deck, when suddenly there was a burst of machine gun fire and bullets spattered into the water near the side of the ship. In a matter of seconds a plane was seen to dive into the water some distance away and all who had seen it gave a cheer thinking it was a Jap. Immediately the ship’s air-raid warning was sounded and all troops had to return to quarters below decks. We had often practised this and lifeboat drill, but this was the real thing, however we were very near to land and didn’t worry. It was not very long before the all-clear was sounded and we were back on deck to see the ship dock and later to learn that the plane which had been shot down was one of ours." Bombardier Nevil C.C. Benham, 35th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment Royal Artillery.

"Shortly after the ship docked our battery was ordered to disembark in order to proceed to gun sights as quickly as possible. There was hurried preparation amongst us and very soon we were ashore and moved along the dock to await transport. Gradually the time passed, the minutes becoming hours until about 6 o’clock in the evening transport arrived, after we had been waiting about five hours on the dock side. This was a good example of the muddle which existed in Singapore." Bombardier Nevil C.C. Benham, 35th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment Royal Artillery.

"Since we were new arrivals from home, we had several visits next day from sailors quartered in the base, many of whom were survivors of the battleship Repulse and Prince of Wales which had been sunk off the coast of Malaya by the Japanese. It was from them that we learned of the conduct of the war in Malaya and the shortage of men and material, which we could hardly believe, having always thought and heard of Singapore as a fortress bristling with guns, but Anti Aircraft Defences were practically nil, whilst fighter defence was actually NIL!" Bombardier Nevil C.C. Benham, 35th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment Royal Artillery.

"One of the transporters in our convoy had 60 fighters on board, all in crates, I don’t think they were ever in operation. Every morning they would take off, that is about 10 or 12 of them and that was a sure sign that the Japanese planes were on their way. Of course the fighters were not on their way to engage them, but were only getting away from the ‘drome’, not to be damaged on the ground. It was almost possible to set a watch by the Jap planes came over each morning. Unlike our planes they came in one line abreast of 27 planes, one would think an easy target for Anti Aircraft Gunners, but I did not see a single plane shot down and of the few shells fired at them, all went wide of the target. It was an unusual sight to see these planes circle over the island dropping their bombs as they wished and all at the same time." Bombardier Nevil C.C. Benham, 35th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment Royal Artillery.

The Fall of Singapore

"It was a time of crying and a time of dying"

Donna Faber

"I put the telephone down. I was thankful to be alone. In all the war I never received a more direct shock," said the British Prime Winston Churchill. He had just received word that Japanese aircraft had sunk two British warships off the coast of Malaya on December 10, 1941. The prime minister was to receive many more shocks over the next two months, culminating with the fall of Singapore on 15th February 1942.

Singapore Docks ablaze ~ By David Ralph Goodwin, RAN

Departure Singapore ~ By David Ralph Goodwin, RAN

Workmen clear up debris in Singapore on January 17, 1942, after a Japanese bombing raid on the British naval base. (AP Photo)

A large freighter settles slowly after being hit by Japanese bombs in Singapore's docks on February 12, 1942. Photo by C. Yates McDaniel, Associated Press correspondent, who was among the last to leave the besieged port that day.

Women and Children first!

"My mother and I were in a cabin originally designed for two but with six berths crowded into it. We only had the one berth between us. My aunt was in another part of the ship. As the ship left the berth we watched my father, wearing not uniform but white shorts and shirt, until he was out of sight, then went below. In one of the last letters we received before he was taken prisoner, he described how he watched us sail out through his very powerful telescope - until the ship finally disappeared." Alison Williams

Women and children evacuating Singapore.

The ship's siren was blowing urgently - it couldn't stay long in Singapore

harbour. From the circle of Daddy's arms I looked up at the ss Narkunda. It

had three funnels. Which one was that terrible noise coming from, I asked

him.

He was just about to say, because I was sure he knew, when Mother pulled at

me. "Will you come along now?"

"No, no," I shrugged her away and buried my face in Daddy's neck.

But he gently turned me around to face my mother and stood up. "It's time

Lief Kintje, time to say goodbye."

I watched the two of them embrace while all around people were screaming and

shouting, running to and fro as if they'd come from the lunatic asylum. The

ss Narkunda gave two more blasts and now there was a far off hum in the sky

which you could just about hear above the din. I could, anyway. Daddy often

said I was so sharp that I'd cut myself one day. He always looked pleased

with me when he said it.

My mother and father were still clinging together, but they didn't kiss,

they stood as if carved from the same piece of granite. As if it was the

last day of the world. I could tell, in spite of all they'd said to me, that

I wouldn't see my Daddy again. Grown-ups always did that - told you fibs

when something was going to hurt.They broke apart and as Mother reached to grab my hand, a distraught Chinese

woman rushed past, nearly knocking her over. It was my chance to leap up

into Daddy's arms.

"Will you come, Jennifer," Mother's voice was getting sharp now. "We'll be

left behind, if not. There's going to be another air-raid and the ship's

going."

My legs pressed harder around my father's waist, my arms nearly choked him.

His horn-rimmed glasses were steamed up from my breath - or was it from his

tears?

The humming in the sky was loud enough for everyone to hear now, and panic

spread like ink on a blotter. Some people fell from the quayside into the

filthy water, as the crowds surged towards the companionway.

A Malay porter, watching our own little tragedy, helped my mother to

disentangle me from my father. Daddy was incapable of it. Together they

dragged me towards the companionway, the tops of my shoes scuffing along the

ground.

Japanese planes screeched by - showering bombs. They missed the ship and hit

the sea with dull thumps. People shrieked in terror and Mother crossed

herself.

"Will you behave, Jennifer? I'm not going to be able to cope, if you don't."

Mother's voice was surprisingly soft. It must have been that, and the sight

of those ugly iron steps leading me away from my father that brought me to

my senses.

As I climbed up, I could see the water below through the metal grid. Broken

wood and rotting vegetables swirled in its darkness. Somebody's hat was

sucked under the hull but there was no sign of the people who'd fallen in.

Every time I looked back for him the crowd had become more dense. I'd lost

him.

"Hurry now," said Mother. "We'll go up on that high deck and wave to Daddy.

Here," she thrust the big doll at me, "you'd better carry this now. And

don't ever lose it - Daddy gave up two precious hours to go home and fetch

it for you."

We reached the top deck and at first I didn't think I'd be tall enough to

see through the rails. But I was. Down below people swarmed like termites.

Flash bulbs were popping and men were shouting. The planes had turned and

were coming back.

"Where is he? Where's Daddy?" I stood on the first rung of

the rails. "I can't see him."

Mother gathered me to her and pointed down. "Stand close, and follow the

line of my finger. There he is. Do you see him now?" She let me go and waved

with both arms. "Wave then, go on, wave!"

I couldn't bring myself to do it. It would mean goodbye and for the moment I

wouldn't allow myself to believe it. He'd understand, he'd know why I wasn't

waving…

The ship shuddered as its anti-aircraft guns fired. More guns blazed from

all around the harbour. This time the planes screamed over us without

bombing.

The Narkunda gave three short blasts, which made everyone near us jump. I

could see the hooter scaling up the nearest funnel. The Military Police were

beating off those that tried to push past and come aboard. One man clambered

onto the gangway as they tried to wheel it away. He was frog-marched down

again. Ropes were thrown into the sea and the ship gave an almighty jerk.

"We're moving!" People shouted and hugged each other, desperate to get

out of Singapore harbour. A bunch of them began to sing and dance with their

children. Apart from the Indian crew I didn't see any other men.

Gradually the crowds thinned out and my Daddy became a spot - still waving.

My insides turned cold and heavy, and I thought about the little statue of

Peter Pan in the garden we'd left behind. He must always feel like this -

even in the hottest tropical sun.

Donna Faber, writing in November 2003

Exhausted British soldiers surrendering to the Japanese, 15th February 1942

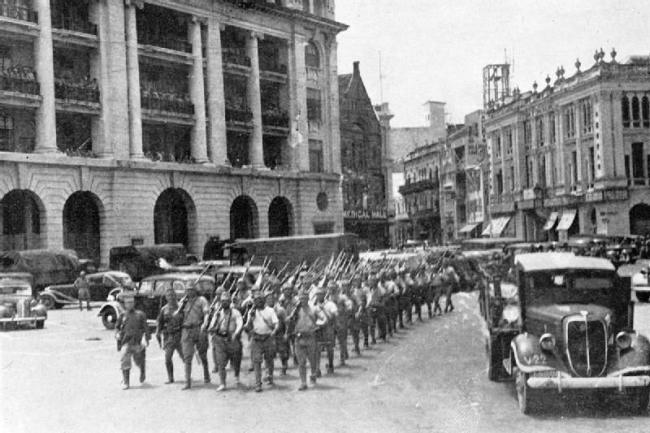

Victorious Japanese soldiers march through Fullerton Square, Singapore. Image:AP

On 24th January 1942, Narkunda reached Australia with her precious cargo....

"After disembarking at Freemantle and handing my family into the care of the Evacuation Committee, Perth, the ship set sail for Portuguese East Africa to pick up other personnel and with Union Jacks on both sides and on her deck, all lights blazing, she was allowed free passage by the Germans to the UK."

On 27th August 1942, Narkunda embarked British Embassy staff and foreign diplomats from Japan.

The NYK 16,975 ton liner MS Tatsuta Maru

The Nippon Yusen Kaisha (NYK) Line's motor ship Tatsuta Maru departed Yokohama on 30th July 1942,with sixty Allied internees on board, including the British Ambassador Sir Robert Craigie and members of the British embassy staff from Tokyo, Yokohama, and Kobe, together with the Belgian Ambassador and Mrs. M. Fortholme, Greek Minister M. Politis, Egyptian Minister M. Samaika, Australian diplomat Keith Officer, Norwegian diplomat and Mrs. M. Kolstadt, Dutch diplomat and Mrs. M. Reuchlin, Czechoslovakian Minister Mr. Havlicek and consular officials from Yokohama and Kobe, and other British and foreign nationals. It was the first Japanese-British diplomatic exchange. After calling at Shanghai, Saigon and Singapore, she continued on to Lourenco Marques, a neutral port in Portuguese East Africa, where she arrived on 27th August 1942. The nearly 1,000 interned Allied personnel on board were exchanged with the British for Japanese diplomats and supplies. She also took on 48,818 Red Cross parcels meant for Allied prisoners of war in Japanese custody. Her British passengers were transferred to the Furness Lines’ SS El Nil, and P & O's Narkunda for the voyage to Liverpool, while other nationalities had to wait for onward transport other ports.

Narkunda and Hong Kong's Second Motor Torpedo Boat Flotilla....

When the Japanese started to invade Hong Kong Island, the Royal navy's 2nd Motor Torpedo Boat Flotilla was ordered to attack and shoot up everything in sight, and to expend all ammunition in the process. Unbeknown to the flotilla, the Japanese had already established a beach head on the Island west of the Sugar Refinery at North Point. Only three MTB's survived to limp back to their base in Aberdeen Harbour. The attack was arguably the most daring daylight MTB attack of all time, and was referred to as “The Balaclava of the Sea.” by Coastal Forces world wide. The crews were hailed as "The bravest of the brave."

Back Row: Lt Kennedy RNVR, Lt-Cmdr Hsu Heng (Henry) CN, Lt-Cmdr Gandy RN (Rtrd), Lt-Cmdr Yorath RN (Rtrd), Cdr Montague RN (Rtrd), Lt Parsons HKRNVR, Lt Ashby HKRNVR, Lt Collingwood RN. Front Row: Sub-Lt Gee HKRNVR, Sub-Lt Brewer HKRNVR, Sub-Lt Legge HKRNVR, and nurses at Waichow.

The crews escaped from Hong Kong and after heroic adventures in China and Burma, reached Bombay and on 26th March 1942, Lt Cdr Gandy and Lt Ashby, and a party of ratings, boarded the ss Narkunda. She slipped at 15:30 hrs bound for Durban, along with survivors from the two Capital ships HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse, both sunk by the Imperial Japanese Air Force on 10th December 1941.

Note: Lt-Cmdr G H Gandy RN led a party of officers and ratings through the Japanese lines and 3000 miles overland through China and Burma arriving in a deserted Rangoon after escaping from Hong Kong on Christmas Day 1941. After five weeks he left onboard the Heinrich Jessen bound for Calcutta along with Lt-Cmdr Gandy, Lt Collingwood, Lt Ashby & the few remaining ratings from Hong Kong. From Calcutta it was a thirty six hour train journey across the Indian sub-continent to Bombay where they boarded Narkunda bound for Durban where they took onboard 657 Italian POW's before shaping course for Cape Town.

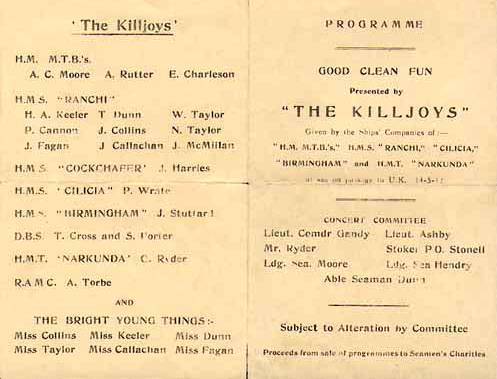

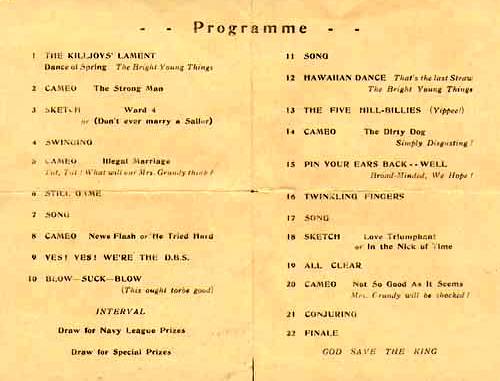

A concert performed by "The Killjoys" billed as "good clean fun" was performed on boar Narkunda on Thursday 15th May 1942. It had been arranged and organized by Lt-Cdr Gandy, Lt Ashby, PO Stonell, & L/S (Pony) Moore and was performed by the various ships companies aboard Narkunda, Ranchi, Cilicia, Cockchafer, and Birmingham. The performers included crew members from the MTB's, (Pony) Moore, Al Rutter, & Eddie Charleson.

As they headed north, frequent life boat exercises were carried out and the order to sleep fully dressed was given as they negotiated the U-boat packs in the north Atlantic continuously zigzagging en route for the UK. From: www.hongkongescape.org

Operation 'Torch' and the end of days.....

Operation Torch was an Allied three-pronged amphibious landing designed to seize the key ports and airports of Morocco and Algeria simultaneously, targeting Casablanca, Oran and Algiers. Successful completion of these operations was followed by an advance eastwards into Tunisia.

Operation Torch convoy. Photo: US Navy

13th November 1942

American Infantry boarding a British landing craft.

Narkunda, under the command of Captain L. Parfitt, D.S.C., was serving as an auxiliary transport during the Allied landings in French North Africa in November 1942. She disembarked her troops at Bougie and had turned about for home when, towards evening on the 14th, she was bombed and sunk some distance off Bougie. Thirty-one persons were killed. Captain Parfitt was among the survivors.

"Bombed and sunk by German aircraft off Bougie, Algeria, passing Cape Carbon (36°52’N-05°01’E). She had just landed troops for the North African campaign and was about to return to the UK when the attack came out of cloud cover and she was hit heavily on the port side and astern. 31 crew were killed. The survivors were picked up by the minesweeper HMS Cadmus and returned to Britain by P&O’s Stratheden and Orient Line’s Ormonde." Source: The P&O Heritage Archive