Please Note: The house flag and word mark 'P&O' are Trade Marks of the DP World Company https://www.dpworld.com/

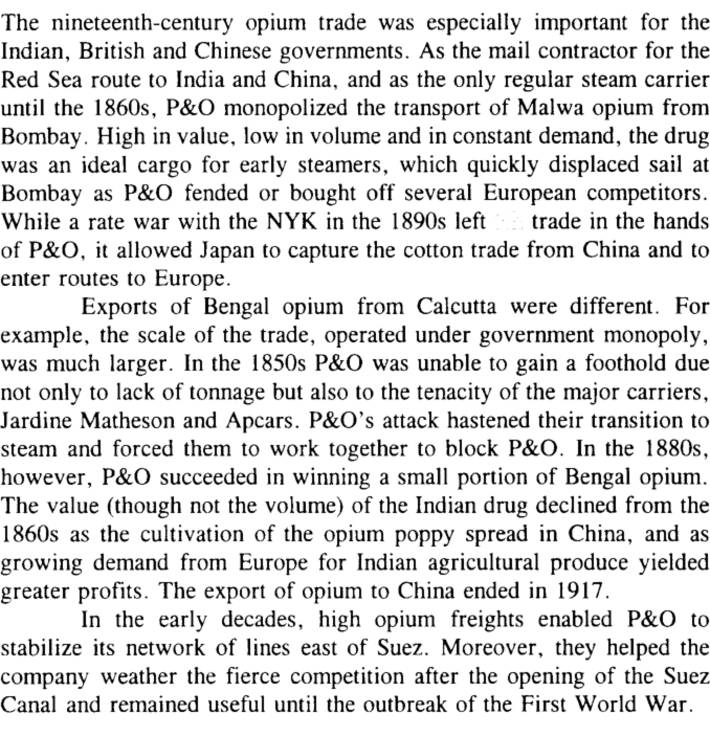

The Governor and Company of Merchants of London Trading into the East Indies, founded on the 31st December 1600 -

Later to become widely known as The East India Company, and colloquially for some years as 'John Company'.......

it held the monopoly on the transportation of Opium from India to China.

The East India Company's armed merchant ships, known as East Indiamen, sailed regularly from the Thames to Bombay, with an alternative route to Madras and Calcutta. These journeys could take anything from 3 to 5 months - each way - depending on wind and weather.

The East India Company's vessel Brunswick’s young doctor, William Jardine, was a key player in the development of the Opium Trade.

View of Jardine's original building from Causeway Bay, Hong Kong, 1846

"The use of opium is not a curse, but a comfort

and benefit to the hard-working Chinese."

Jardine Matheson & Co ~ 1858 Press Release

China's biggest opium importer.....

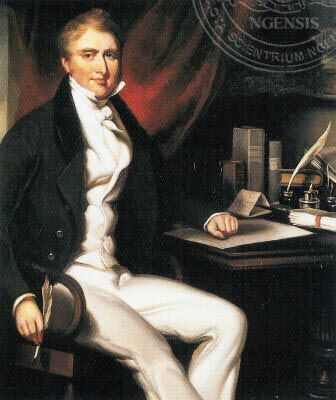

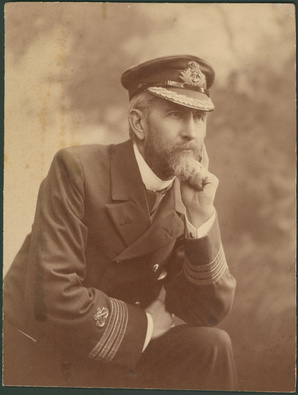

Dr William Jardine, in his study, c1832

In 1802, Jardine, having attended the University of Edinburgh, was awarded a diploma from the Royal College of Surgeons.

The following year, he signed aboard the East India Company's ship Brunswick, as a surgeon's mate and set sail for India.

William Jardine’s time as an East India Company doctor was almost at an end, when he first had plans to set up a trading house in Canton.

That trading house still exists, as a conglomerate with a market capitalisation of more than $40 billion.

Under a charter granted to the East India Company by King Charles I of England, its directors in London’s Leadenhall Street held a monopoly on British trade between India and China. Jardine was employed in this trade, sailing between Calcutta and Canton.

It was then customary for the Company’s servants to conduct a certain amount of private business on their own account. In order to regularise this, the East India Company allowed each officer and member of the crew a space about equal to two chests. What the men did with this space was their own business. Using his allotted space, the young doctor soon discovered that trading illegal narcotics was more profitable than practising medicine.

It was during these early days that Dr William Jardine found himself onboard a ship captured by the French with all its cargo seized. Despite this setback a trading partnership formed at the time by Jardine with a fellow passenger, a Parsee Indian called Jamsetjee Jeejebhoy, would endure for many years.

Jardine’s company became enormously successful, monopolising the market with one particular commodity, one that was much more profitable than cotton, and one whose demand was exploding because the British had got millions of Chinese hopelessly addicted to it: opium.

Opium wasn’t just another trade good for the British Empire. It was the necessary corollary to another commodity: tea. The British were importing tens of millions of pounds of tea from China every year. There seemed to be no end to the demand and everyone involved was making huge profits. There was just one problem. They didn’t have the cold hard cash or rather, cold hard silver to pay for it.

With all of the Empire’s physical currency disappearing into China, the British were running a huge trade deficit.

They urgently needed something that the Chinese wanted as much as the British wanted tea. Opium was the answer. And form years, it was essential in keeping the Empire’s entire economy afloat.

The East India Company was effectively the ruler of territories vastly larger than the United Kingdrom itself. In addition, it also created, rather than conquered, colonies.

.jpg)

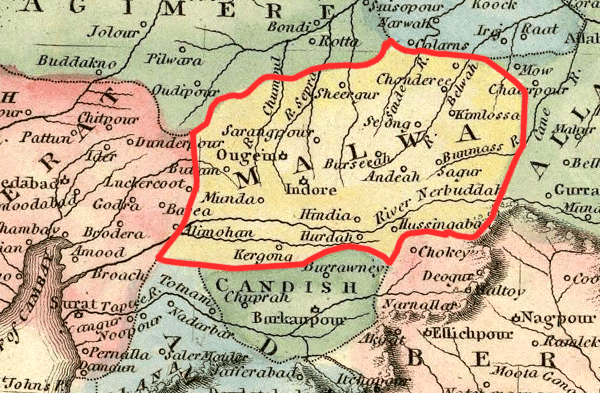

Malwa

Opium was grown in the Company's territory of Malwa, from where it was shipped to Bombay. At its height, almost one-third of the entire trade was going to one firm - Jardine’s trading house in Canton.

And the man who enabled this trade from India was fast becoming stunningly wealthy.

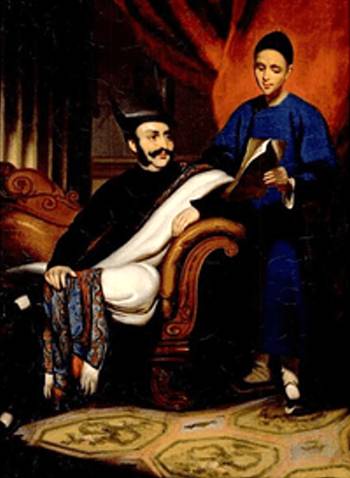

His name was Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy ......

Later to become, Sir Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy, 1st Baronet Jejeebhoy of Bombay,

Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy was born in Bombay in 1783.

In 1805 he had the great good fortune to make friends with the East India Company's vessel Brunswick’s young doctor, William Jardine.

This chance meeting turned into a friendship “that would change both men’s lives and influence the course of history.”

Two decades after Jejeebhoy and Jardine met, Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy & Company and Jardine Matheson & Company formed an enormously effective collaboration. Through the 1830s, Jejeebhoy was the largest consigner of opium to Jardine, who grew to be the richest Tai-Pan of them all.

In 1842, Jejeebhoy became the first Indian to be knighted by Queen Victoria, and in 1858 the first to be awarded a baronetcy. His charitable endeavours helped build a modern city, and his name is dotted around the metropolis, a hospital here, a school of art and architecture there. The causeway connecting the former islands of Mahim and Salsette is named after his wife Lady Jamsetjee.

The East India Company auctioned the product in Calcutta rather than selling it in Canton to avoid accusations of trafficking in contraband, leaving trading houses such as Jardine Matheson to deal with smugglers, who peddled the product upriver and transported it to every part of mainland China.

Seal of the Qing

The Qing was the last in the imperial history of China.

It was established in 1636, and ruled China from 1644 to 1912, with a brief restoration in 1917.

.jpg)

The Flag of China 1889 - 1912

The Qing, perpetually viewing themselves as victims, played into the arrogance displayed by the British.

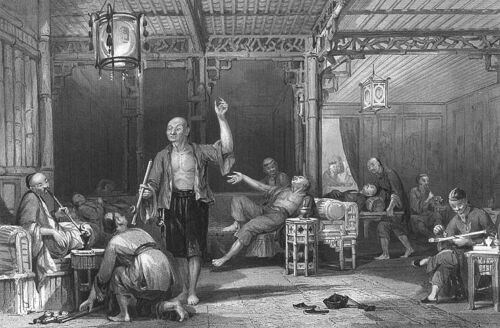

While there was a growing culture of opium use in the Qing Dynasty leading up to the Opium War, the British were all too willing to provide the supply to meet this demand in exchange for financial gain......

.........and tea.

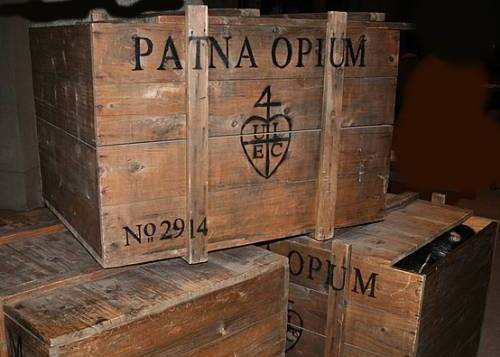

The amount of opium imported into China, increased from about 200 chests annually in 1729, to roughly 1,000 chests in 1767 - and then to about 10,000 per year between 1820 and 1830.

The weight of each chest could vary - depending on its origin - but averaged approximately 140 pounds.

By 1838 the amount had grown to some 40,000 chests imported into China annually. For the first time, the balance of payments began to run against China - in favour of Britain.

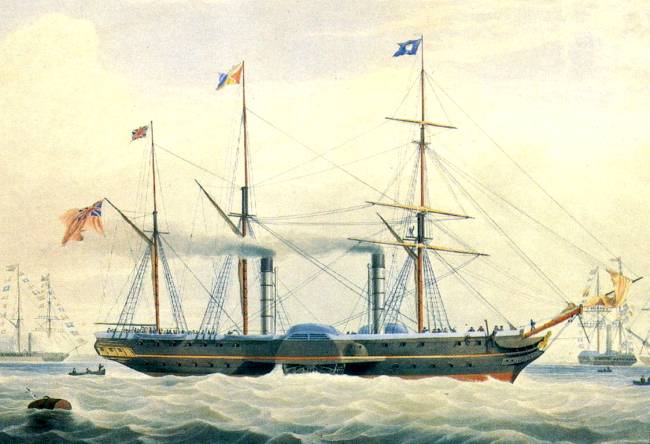

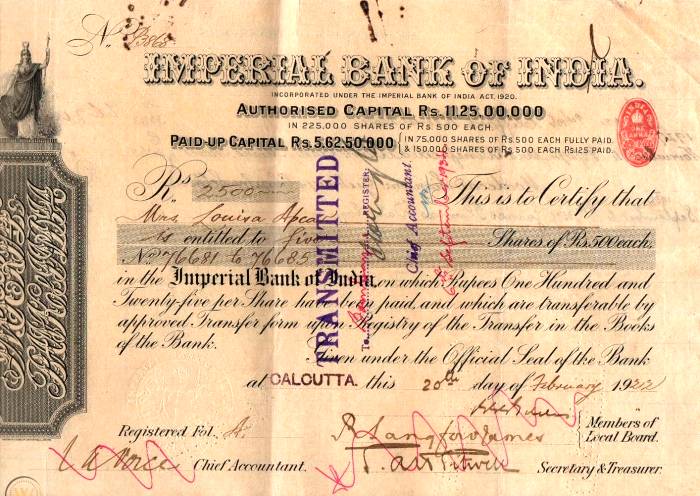

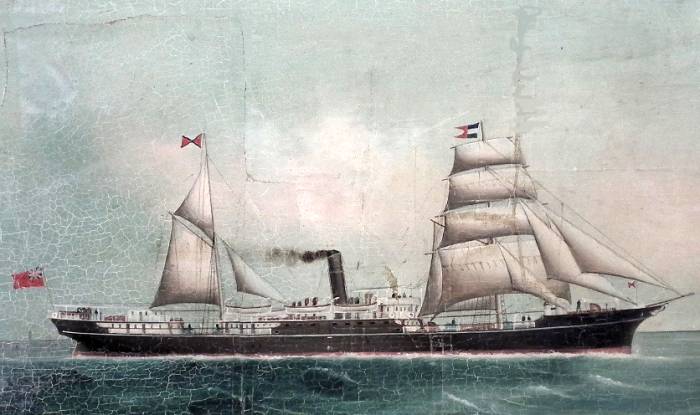

The P&O's ss Hindostan - the first steam ship to run between the Suez Canal and Calcutta.

Departing from Southampton on the 24th Sept 1842, she opened an era of comprehensive Steam Communication with British India...

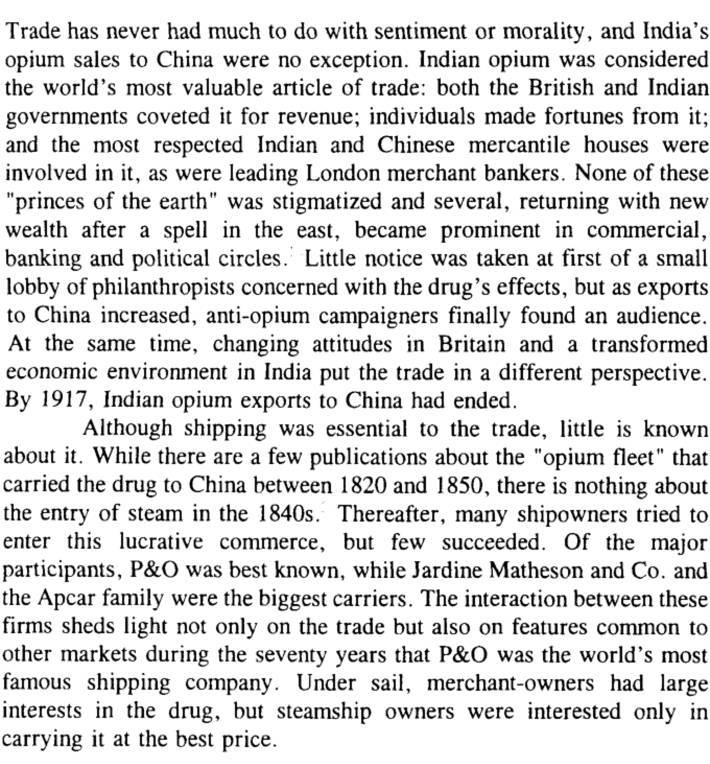

P&O monopolised the transport of Malwa opium from Bombay until the 1860s, and in 1880, secured a lucrative contract to transport Bengal opium.

In 1873, P&O named their latest steamship, Malwa, on the London - Bombay schedule.

P&O's ss Malwa

Contrary to a widely held belief, the British neither introduced opium to India, or turned it into a commodity. Opium has a long history on the subcontinent, both as a medical and recreational drug, and also as an item of trade.

One approach to determine the origin of opium in India is to look at the etymology of the Hindi term for opium: 'afim'. It can be traced back via Sanskrit to the Arabic name 'afiyun'.

Following this approach, it could be concluded that the Arabs were responsible for introducing opium to India.

Soon, a network of opium distribution had formed throughout China, often with the connivance of corrupt officials.

Levels of opium addiction grew so high that it began to affect the imperial troops and the official classes.

The efforts of the Qing dynasty to enforce opium restrictions, resulted in two armed conflicts between China and the West, known as the Opium Wars - both of which China lost and which resulted in various measures that contributed to the decline of the Qing.

The first war, between Britain and China (1839–42), did not legalize the trade, but it did halt Chinese efforts to stop it.

In the second Opium War (1856–60) - fought between a Franco-British alliance and China, the Chinese government was forced to legalize the trade, but benefiting via a modest import tax. By that time opium imports to China had reached 50,000 to 60,000 chests a year, and they continued to increase for the next three decades.

By 1906, however, the importance of opium in the West’s trade with China had declined, and the Qing government was able to begin to regulate the importation and consumption of the drug.

In 1907 China signed the Ten Years’ Agreement with India, whereby China agreed to forbid native cultivation and consumption of opium on the understanding that the export of Indian opium would decline in proportion and cease completely in 10 years.

The trade had thus almost completely stopped by 1917.

English Tea Pots and Cups c. 1740 – 1810 from the Milwakee Art Gallery

This great demand for tea from Europe, particularly England, resulted in a net trade surplus of about £150 million worth of silver by 1817 for the Qing Dynasty. This trade deficit came about because the Qing were simply not as interested in British goods as the British were in Tea.

Without anything to trade for tea the British were forced to pay in silver.

In order to avoid continually running at a loss in their trade with the Qing, the British East India Company began importing opium into China. This created a triangular trade between England, China and India.

Opium Ships off Chusan Island - engraved by E Duncan after a picture by William John Huggins.

Source: Freda Harcourt ~ International Journal of Maritime History

'Apcar & Co' was founded in 1819, in India, and was engaged in shipping, import and export. The most profitable trade was in opium, shipped from

India to Hong Kong and the Pearl River.

The Apcar Line also carried Indian and Chinese laborers for work in Malaya and Singapore. The first of the Apcar family arrived in India from Armenia, in around 1795.

Until P&O began shipping opium from Calcutta in 1851, the trade was divided between Jardine Skinner and Company, a trading company based in Calcutta, founded in 1825, and the Apcar Line. Even then, P&O had limited shipping capacity. While Jardines carried opium for the larger suppliers, the Apcars with their Arratoon Apcar and Catherine Apcar vessels catered to many of the smaller local dealers.

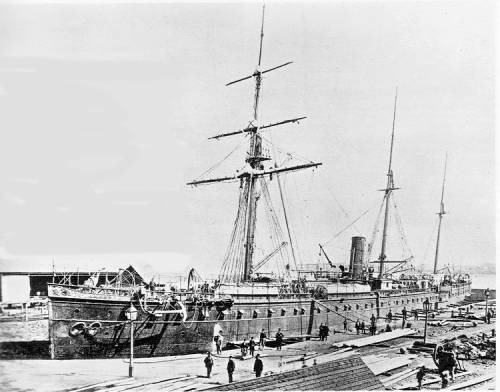

The ss Catherine Apcar

The ss Arratoon Apcar

Built by James Henderson and Son of Renfrew, Scotland in 1861, this iron-hulled steamer measured 262 feet long, had a 35 foot beam,

displaced 1480 tons, and was powered by a 250 horsepower engine.

With slower ships, they charged much lower rates than Jardine Skinner & Company, which was closely associated with Matheson & Company of London and Jardine Matheson & Co. of Hong Kong.

East India Company opium chests.

Apcar's freight charges ranged from 8 - 10 Rupees per chest - compared to upward of 28 Rupees per chest charged by Jardines and Skinner.

However, the Apcars may have had private arrangements with the dealers that locked them into using Apcar services.

The Apcar Line's fleet became well-respected, efficiently carrying both cargo and Chinese coolies, mostly between Singapore, Hong Kong and Amoy, but also making regular voyages as far as Japan.

Pirates were active, and well into the twentieth century, the ships had to be armed and sandbagged against attacks.

From 1875-80 Captain Chapman James Clare served on the opium steamers of Apcar & Co. trading between Hong Kong and Calcutta.

The Apcar Line was sold to the British-India Steam Navigation Company, for Rs 800,000 in 1912.

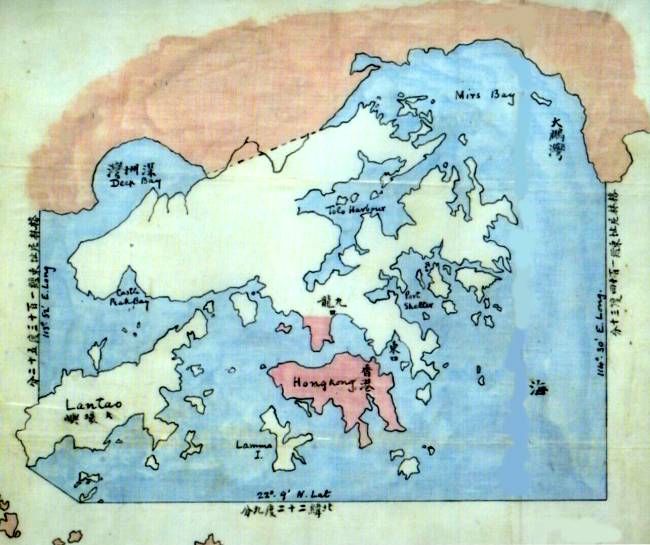

The colony grew into a flourishing free port and centre of international trade. Its population increased rapidly and in 1860 it was extended to include the neighbouring Kowloon Peninsula.

Towards the close of the 19th century, Hong Kong was becoming overcrowded and its authorities wanted a further extension. The United Kingdom's government also had political reasons for desiring its expansion: a larger Hong Kong would make the colony easier to defend and safeguard British influence in China at a time when French. German and Russian interests in the region were strengthening.

On 9th June 1898 British and Chinese representatives signed a treaty offering the United Kingdom a 99 year lease of an area subsequently termed the New Territories. This area (shown in white on the map) was more than four times the size of the existing colony (coloured pink) and comprised some 200 islands, as well as a slice of the mainland The lease began almost immediately on 1st July, but formal ratification of the treaty was not signed until 8th August.

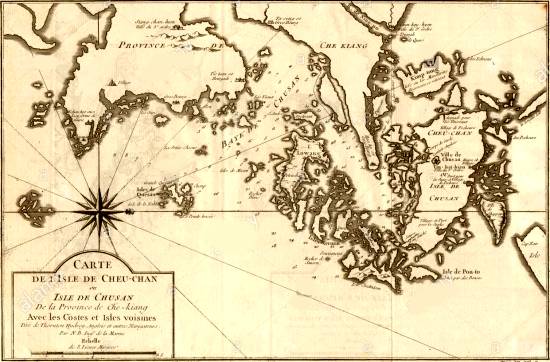

'L’lsle de Cheu-Chan'. Ningbo city & Zhoushan Island. Bellin 1748 map

When the British diplomat Sir George Staunton arrived in Zhoushan (or Chusan as it was known in the West) aboard HMS Lion in 1793, he warmly described the island’s main harbour town of Dinghai as comparable to Venice.

"We must religiously observe our engagements with China, but I fear that Hong Kong is a sorry possession and Chusan is a magnificent island admirably placed for our purposes," wrote the home secretary Sir James Graham to the prime minister Sir Robert Peel, as British diplomats prepared to return the island of Chusan to Chinese rule during the winter of 1845.

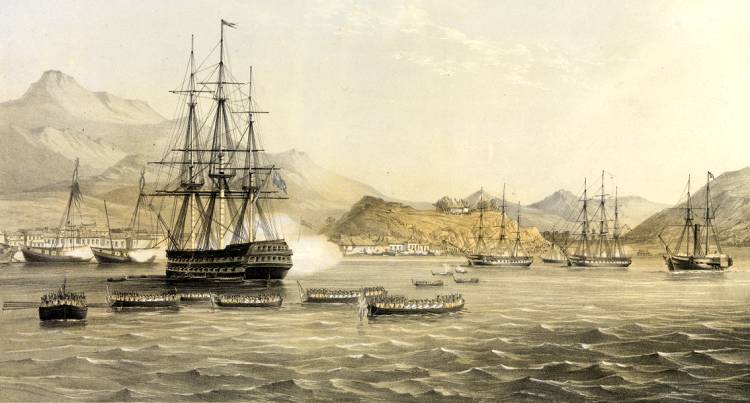

Taking the island of Chusan by the British, 5th July 1840 - drawn by Harry Durell.

Before the Union Jack ever flew over Hong Kong, it had been raised on Chusan.

The British wrested Chusan from the Qing dynasty, only to hand it back for the sake of Queen Victoria's honour and Britain's national prestige.

Opium played such a significant part in P&O’s history and prosperity in the nineteenth century, that much of the later success of the company can be attributed to this trade alone.

Prior to the advent of steamships, there had been a thriving opium trade with China, from Bombay and Calcutta, by sailing ships.

Opium, with its low volume and high value, was the ideal cargo for steamships.

P&O's 1844 Government contract to establish steamship services East of Suez, gave the company a foothold in the lucrative opium trade.

With the completion of each stage of its strategy, the company bedded itself the more surely as the sole custodian of the great Eastern trade routes. The very success of this exemplary enterprise made newcomers look enviously at what P& O had achieved and tempted them to emulate it.

The future is steam......

The Victorian period saw a drastic change in attitude towards the Chinese

For much of the 18th Century, China was regarded by the British as an orderly and ancient civilisation whose artefacts, particularly porcelain were valued by the rich. China tea was becoming the nation's most popular drink. Yet within eighty years, by the 1840s government in China had changed and along with that attitudes towards China changed. It was being claimed in the 1840s that the Chinese people were clamouring for British goods that were being denied them by their rulers. What had happened to produce such a drastic change in attitude?

To begin with there had been a change in its rulers in China, with the Manchus not wanting associations with European powers and being suspicious of their motives. The British had embraced free trade and wanted access to all possible markets, in order to provide markets for all that was being produced in Britain and in her empire. Where there was resistance to receiving British goods, the government did all it could to open up countries to British trade. Whilst the East India Company provided tea for the British market in its ships from China, the Company sought to use the monopoly in the harvesting and trade in opium that it had from 1773, to export to China. This coincided with a period of decline for the Manchu dynasty that made it all the more reluctant to accept closer connections with European powers.

In 1793 and 1816 there had been two British missions sent to China in order to establish diplomatic links but neither of them made any progress. It was perhaps inevitable given the weakness of the Chinese state and the British search for new markets for their goods, that there would eventually be a clash with China - and this came in 1839.

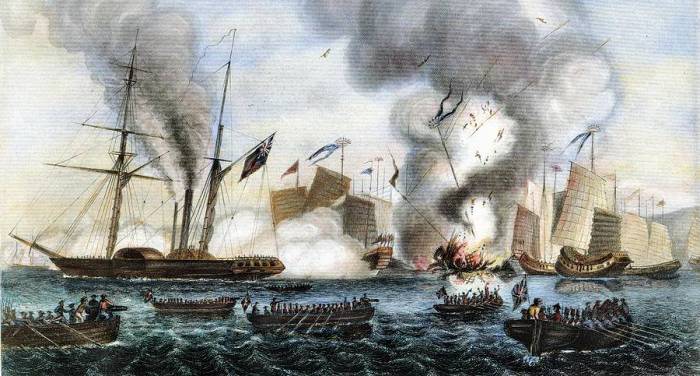

The First Opium War of 1839-

The Opium Wars arose from China’s attempts to suppress the opium trade.

Foreign traders - primarily British - had been illegally exporting opium mainly from India to China since the 18th century, but that trade grew dramatically from about 1820. The resulting widespread addiction in China was causing serious social and economic disruption there.

In the Spring of 1839, the Chinese government confiscated and destroyed more than 20,000 chests of opium - some 1,400 tons of the drug - that were warehoused at Canton.

Canton was the main port open to trade with China. The Chinese commissioner in Canton, Lin Tse-

20,000 cases of illegal British opium were seized and the British communities in Canton and Macau were expelled.

Although the East India Company had lost its monopoly, the profits from the opium trade still accounted for 40% of the total value of Indian exports and the money made was often more than the sum total of the interest payable on loans received by the company from London. The EIC and the British government was not willing to allow this situation to go unchallenged.

Consequently the Foreign Secretary, Palmerston, authorised the sending of an expedition consisting of a fleet of gunboats and 4,000 troops to the mouth of the Canton River.

The British used all the modern technology available, and at the start of the conflict, seized Hong Kong and annexed it for use as a naval base, then sent gunboats up the Yangste River to shell Shanghai and Chungking, before taking them by landing forces. While the British killed many Chinese with their superior fire power, they lost men to sunstroke, malaria, dysentery and cholera.

The result of the Yangste campaign was that the Chinese government signed the Treaty of Nanking which confirmed British possession of Hong Kong and the use of Canton as a trading base - together with the opening up of Amoy, Foochow, Shanghai and Ningpo - as additional trading bases.

The Second Opium War 1856 - 1860

This war exposed China's military weakness and established Britain as the dominant power in the Far East.

Using the newly acquired port of Hong Kong, Britain sought to make the coastline and rivers of China safe for trade by eliminating piracy. This was popular work for the crews which could earn good money from the bounties won.

Relations between the two governments were not good - and not helped by the actions of British warships.

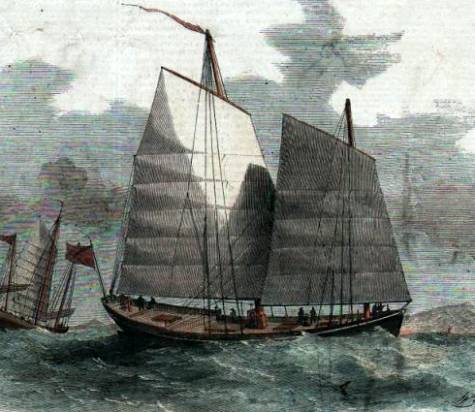

Lorcha - junk rigged with Chinese-style batten sails on a European-style hull,

which made the lorcha faster and able to carry more cargo than the normal junk.

War was provoked in 1856, when on the 8th October, Cantonese soldiers boarded the British registered 'Lorcha'Arrow and hauled down her Red Ensign. The claims to her being British were in fact doubtful - as the vessel's registration had lapsed.

The British captain of the Arrow reported the incident to the consul in Canton who demanded the release of crew members - some of whom were former pirates known tothe Chinese.

Chinese officers tear down the Arrow's British flag on the 8th October 1856.

Harry Parkes, the Canton consul appealed to Bowring, the Governor of Hong Kong who, seeing an opportunity to extend his area of control, agreed to becomeinvolved and ordered a British gunboat to board a Chinese vessel . As the crisis escalated a squadron of the Royal Navy was sent up the river to

bombard Canton and blockade the city. The British cabinet was not whole heartedly in support of Browning's actions but they decided to

support him in the interests of trade and to punish the Chinese authorities. The support of the Cabinet for what Richard Cobden described as an

illegal action prompted in January 1857 a heated debate in Parliament. In the House of Commons with Palmerston warning the Commons not' to

abandon a British community to a set of barbarians.' It was not enough to prevent Cobden's motion of censure to win by 263 votes to 247.

Palmerston, now the Prime Minister appealed to the country in

a General Election which he lost to a Whig-

The Treaty of Tientsin, now also known as the Treaty of Tianjin, is a collective name for several documents signed at Tianjin (then romanized as Tientsin) in June 1858. They ended the first phase of the Second Opium War, which had begun in 1856.

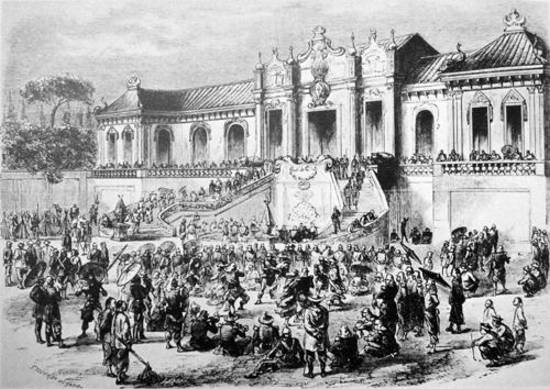

The Sacking of Peking

Meanwhile Lord Elgin had been sent by Palmerston to China as an envoy to negotiate with the Chinese government to end the impasse over the Arrow.

Elgin was joined in Hong Kong by a French envoy sent by Napoleon III to get compensation for the execution of a French missionary. The two envoys

eventually authorised an attack on Canton itself and with 2,000 soldiers newly arrived from Calcutta and a powerful French fleet, the city was

bombarded and then entered. The victorious troops stripped the city bare with Elgin himself taking 52 boxes of silver and 68 boxes of gold ingots.

The allies deposed the Commissioner and replaced him with his deputy. The Imperial government refused to accept the situation so an allied fleet of

gunboats attacked and took five forts at the mouth of the Peihu river. This forced Chinese Commissioners to agree to what became the Treaty of

Tientsin signed in 1858 by which China would pay £5m in war reparations, the opening up of China to Christian missionaries, the freedom of

Europeans to move anywhere in China and a permanent representative in Peking. The Imperial government was slow to ratify the treaty and this

produced the Third Chinese war of 1860. Frederick Bruce, Elgin's brother was sent to Peking with a fleet of sixteen warships but the fleet failed to breach the booms put across the mouth of the River Peiho. By the time the news reached London Palmerston was back in power and he was determined that British prestige must be repaired. A large British and Indian force of 13,000 troops was sent together with 6,500 French troops to the mouth of the Peiho. The force took the forts at the mouth of the river without too much difficulty and then began their march on Peking.

Having arrived at the outskirts of Peking, the Emperor sent envoys to let it be known that two new commissioners had been appointed to begin

discussions. After a number of exhaustive meetings, the Chinese commissioners agreed to all the allied demands - but then a party of British envoys was captured by a Tartar force. Elgin decided that it was time to use force rather than diplomacy against this Tartar army which was attacked before Peking.

The much larger Tartar army was defeated and forced to retreat but not before they had beheaded two prisoners. As well as the retreat of the Tartar army, the Emperor himself fled - leaving Peking to the allied army.

The looting of the Summer Palace by Anglo-French forces in 1860.

They then burned the magnificent building to the ground in a terrifying act of sheer vandalism.....

"We call ourselves civilized and them barbarians," wrote the outraged author, Victor Hugo. "Here is what Civilization has done to Barbarity."

The Summer Palaces which contained the pick of Chinese art treasures was looted - despite an agreement with the Allies to preserve the treasures. Among those horrified by the looting was Charles Gordan, later to gain fame in Khartoum. Wolseley who was General Hope Grant's military secretary, believed that the looting and the destruction of the Palace ordered by Elgin in October helped to hasten the signing (by the Emperor's brother Prince Kung) of the 1858 Treaty of Tientsin.

As well as ratifying the earlier treaty, Kung and Elgin agreed the transfer of Kowloon to the British.

The expedition had been enormously successful with few military

casualties, huge

reparations, and the permanent annexation of Kowloon to add to Hong Kong.

It was perhaps ironic that Elgin, the man who had saved the Parthenon friezes,

destroyed one of the wonders of the world -

It is important to point out that not everyone in Britain supported the opium trade in China. In fact, members of the British public and media, as well as the American public and media, expressed outrage over their countries’ support for the opium trade.

on October 8, 1856, Qing officers seized and boarded the vessel Arrow at anchor in Canton harbor.

The Arrow was a lorcha — a hybrid ship design with a European-style hull and Chinese rigging — that worked the southern Chinese coast and Pearl River Delta, calling at ports like Guangzhou, Hong Kong, and Macao. Arriving at Guangzhou on October 3, she sat there for a few days until the local authorities received a tip identifying one of her crew as a pirate who had just taken part in a skirmish a few days earlier. In response, Yè Míngchēn 叶名琛, the top Qing official in Guangzhou, ordered his police to board the Arrow and apprehend the crew.

This web page dated: 18th March 2020