The 'vital sparks'

The wide use of spark-gap transmitters led to the nickname 'sparks' for a ship's radio officer -

an integral part of life on board ships in the days before satellite communications rendered the job obsolete. Today, ships comply with GMDSS - Global Maritime Distress and Safety System - communication standards, which no longer require the services of a dedicated radio officer. Highly automated shipboard satellite communications systems incorporate voice, SMS and internet, globally. Once the 'Master under God', and able to act autonomously, today's ship's captains have to contend with a steady stream of head office communications and junk e-mail, just like the rest of us......Before there was wireless, there was the Morse Code....

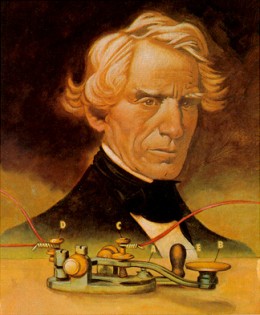

Starting in 1836, the American artist Samuel F.B.Morse developed the forerunner to modern International Morse code.

The original Morse Code was inadequate for the transmission of much non-English text, since it lacked codes for letters with diacritic marks. To remedy this deficiency, a variant called the International Morse Code was devised by a conference of European nations in 1851. This newer code is also called the Continental Morse Code.

Some History...

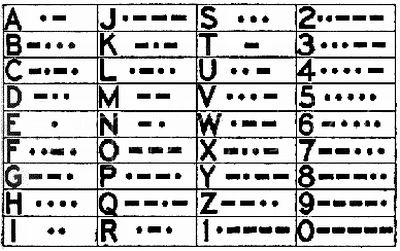

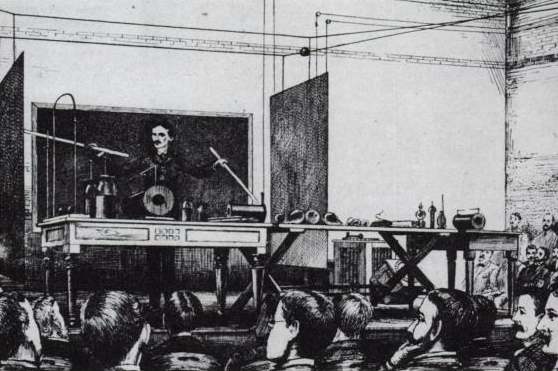

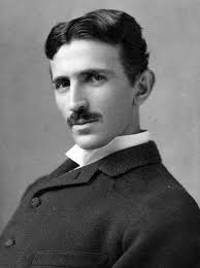

Nikolai Tesla, a Serbian-American, in his "Experiments with alternate currents of very high frequency and their application to methods of artificial illumination" lecture of 1891, demonstrating wireless transmission of power and high frequency energy at Columbia College, New York

After continued research, Nikolai Tesla presented his ideas on wireless communication in 1892 and further expanded on them in 1893.

and then, along came Marconi....

Guglielmo Marconi, an Italian inventor, arrived in Britain in 1896, determined to develop Hertzian Waves - an electromagnetic wave, usually of radio frequency, produced by the oscillation of electricity in a conductor - into a commercial system from which he could make money. With an extensive network of telegraph cables already encircling the globe, he realised that a wireless system would be in direct competition with these well-established landlines.

Marconi

directed his early efforts at developing a wireless telegraphy system for maritime use, reasoning that with the ever increasing number of people travelling the oceans of the world, he would be able to make his fortune. Marconi's 'Wireless Telegraph and Signal Company' was formed on 20 July 1897, after the granting of a British patent for wireless in March of that year.

In 1899, experiments with his wireless communications system on board the liner St Paul, followed by the ss Philadelphia some three years later, heralded the introduction of Marconi wireless telegraphy systems at sea. Systems that were to operate until the introduction of modern geostationary satellites, which eventually rendered the ship's highly skilled Radio Officer redundant. In 1909, Guglielmo Marconi shared the 1909 Nobel Prize in Physics with Karl Ferdinand Braun "in recognition of their contributions to the development of wireless telegraphy".

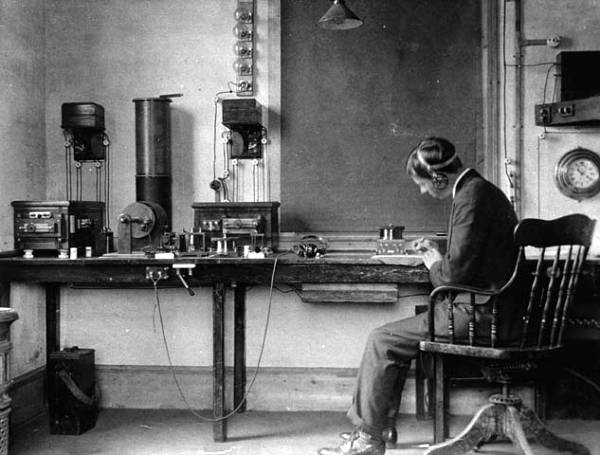

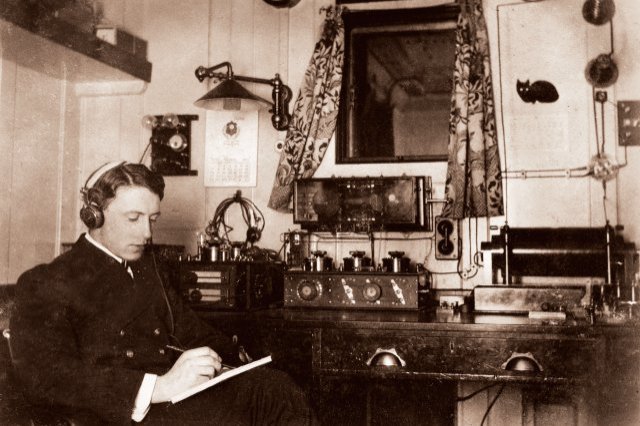

The most famous of all the Marconi men, Titanic's heroic Senior RO, Jack Phillips, aged 25.

A reconstruction of Titanic's radio office, from the James Cameron movie..

Radio Officer Jack Phillips in the Titanic's Radio Office.

The

Marconi equipment was delivered to Titanic in time for sea trials on 2nd April.

Jack Phillips and his deputy, Harold Bride, spent the day completing the

installation and adjusting the equipment. They exchanged test calls with coast

stations at Malin Head (North coast of

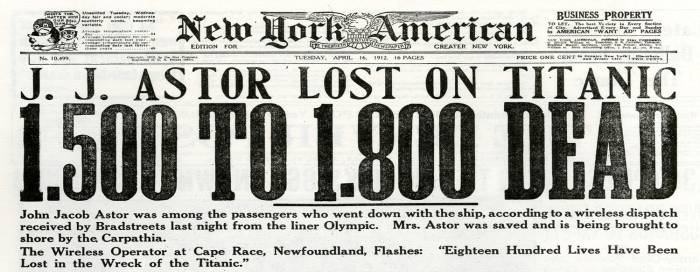

"Come as quickly as possible old man: the engine-room is filling up to the boilers...." Radio Log of the ss Carpathia,

The Safety of Life at Sea

-SOLAS Convention codified the requirements for the provision of

wireless and wireless operators on certain ships. The sinking of the White Star

liner Titanic on 15th April 1912, brought home to all concerned the urgent need

to provide properly for emergency situations. The introduction of the first

SOLAS Convention was delayed by WW1 - the Convention came into force in the

early 1920's, with the following protocols:-

- carriage requirements and radio watchkeeping

hours were standardised;

- message priorities were standardised - i.e.: distress and safety traffic

always has priority;

- distress frequencies were standardised; and

- radio silence periods were introduced.

A Marine Auto-Alarm set, designed and manufactured by the Marconi International Marine Communication Co. Ltd., c. 1920. This system was just one outcome of the Titanic disaster. If a ship had only one wireless operator, he could sleep without fear of missing an emergency message.

The Jack Phillips

memorial and cloisters at Godalming, where Jack came from, after attending

a local school in Farncombe.

The memorial is a fitting tribute to Jack, probably the most famous Radio

Officer of all time. In the Godalming Museum, they have a corner dedicated to

Jack, where people come from all over the world to visit. Photograph and

details courtesy of Ted Sapstead, P&O Engineer Officer 1957-1962.

The early days....

During the 1920's, 30's and 40's, marine radio advanced with the technology of the day - radiotelephone operation was introduced, and most importantly, High Frequency (HF) came into widespread use, thereby allowing communications over ever-increasing distances.

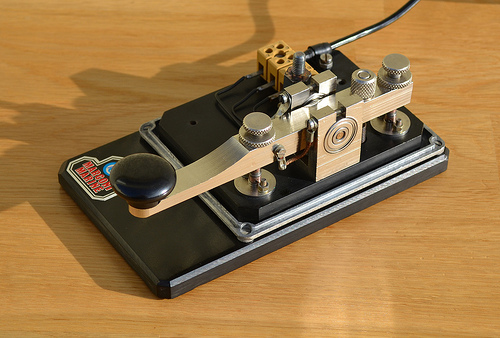

A Marconi M.I.M.C. Co. Key Type 365A Key, serial number 4448, late 1930's, from the ss Strathmore, callsign GYMS, 1930's.

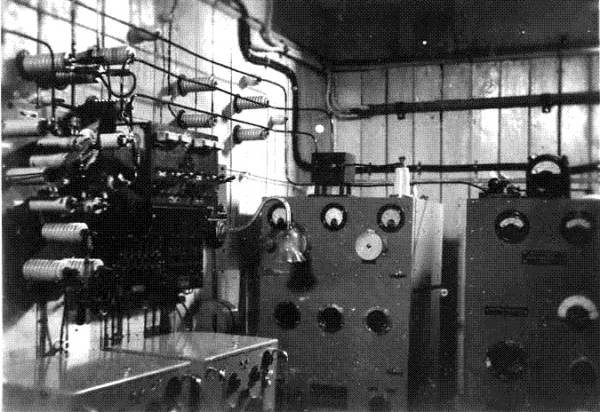

Radio Room of P&O's ss Maloja - Callsign GFBD - Marconi 381 and H/F counterpart

Note: In September 1939, Maloja was converted to an armed merchant cruiser in Bombay. As part of the conversion the after dummy funnel was removed, the radio room demolished and a new W/T office set up in the space under the bridge. The above photograph was taken after the conversion. She commissioned as HMS Maloja on 24th November 1939.

Marine radio played

a vital role in WW2 - the war provided a great boost to radio technology in

general. Amongst other things, WW2 introduced direct bridge to bridge

communications, through the use of what was to become the marine VHF radio band

- known during the war years as "talk between ships" (TBS).

After the war, Marine Radio incorporated the latest achievements in electronics

- solid state (i.e.: transistorised) equipment and Marine Radar became

commonplace.

The end of days.....

By the late 1970's, despite tremendous general advances in

communications, Morse Code still ruled the marine radio waves.

Radio Officers sent distress

messages by Morse Code (or radiotelephone) in the hope that another ship or

shore station would hear the call and respond.

In 1979, the

International Maritime Organsiation Assembly decided that a new global distress and

safety system should be established, in conjunction with a coordinated SAR- Search And Rescue

infrastructure to improve safety of life at sea.

And so was born the Global Maritime Distress and Safety System (GMDSS).

Designed to automate a ship's radio distress alerting,

it removes the requirement for manual watchkeeping on

marine radio distress channels.

The new system is quicker, more efficient and reliable than the old manual Morse

Code and radiotelephone alerting systems.

The basic concept of the GMDSS is that Search and Rescue (SAR)

authorities ashore, as well as shipping in the immediate vicinity of the ship or

persons in distress will be rapidly alerted so that they can assist in a

coordinated SAR operation with the minimum of delay.

Well paid to see the World.....

Sparks would have to monitor the 'traffic lists' from a number of shore stations, where all ships that needed to receive messages had their call signs listed in alphabetical order. If a ship heard his call sign, the radio officer would then try to contact the shore station in order to get the 'traffic'. It was often a lengthy procedure, and seldom could you send out a query and get an answer back in the same day. The ship's captain had to be trusted to conduct business with little real-time input from the company.

The Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company Limited was pre-eminent. Formed in London in 1897 by Senor Guglielmo Marconi who opened a factory in Hall Street, Chelmsford, Essex in 1899, employing 26 men in the manufacture of wireless telegraph equipment, under the Company's trading name 'The Wireless Telegraph and Signal Company Limited'.

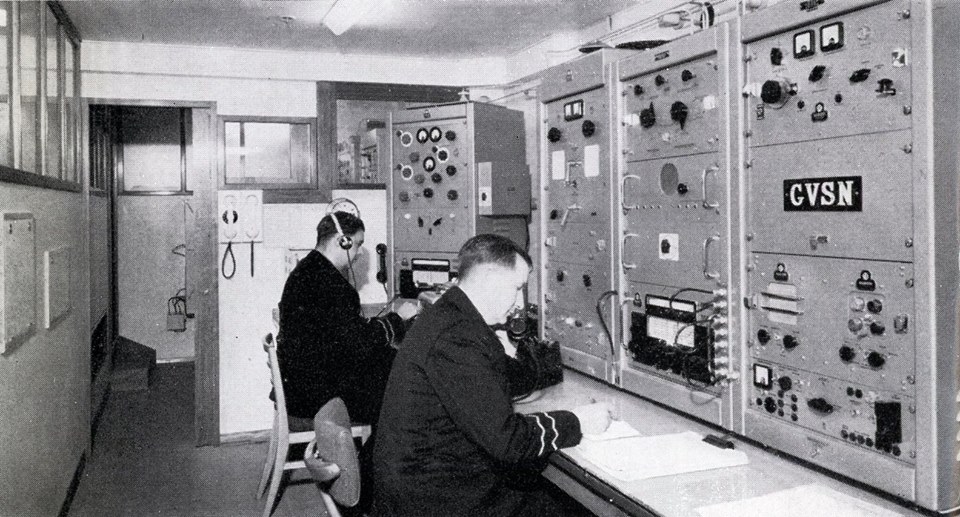

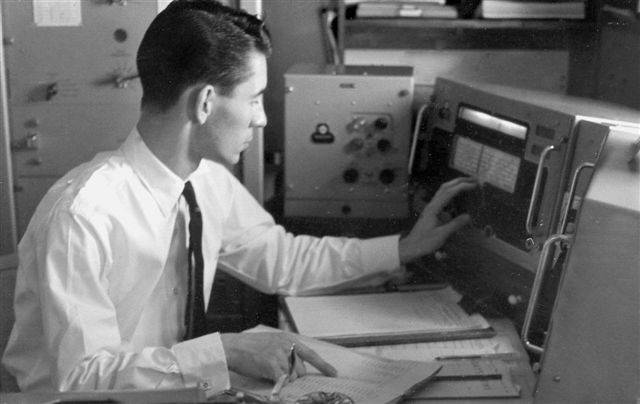

The radio room of P & O's ss Devanha call sign GFBR in 1957, with a CR300 receiver on the left.

Note: Devanha, from an Urdu word meaning ‘hopelessly smitten by’, was a Canadian-built general cargo ship of 10,190 tons, acquired by P&O in 1947, and sold

in 1961.

The Marconi CR300 single conversion, superheterodyne receiver. 15 KHz to 25 MHz in eight bands, manufactured between: 1943 and 1946

ss Oriana's Marconi Radio Officers in the early 1960s.

P&O Liner Oronsay, GCNB ~ Marconi RO Derek Rice at the W/T operating position in 1969.

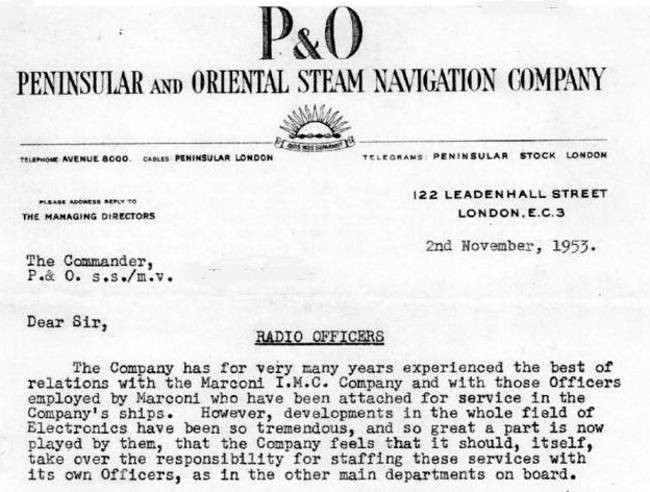

P&O bought out the remaining stake in Orient Lines in 1960 and renamed its passenger operations P&O-Orient Lines. Unlike P&O passenger ships, Marconi Radio Officers continued to be employed aboard Oriana, Orsova, Oronsay and Orcades, P&O having dispensed with Marconi Radio Officers on board the Company's ships in late 1953. At that time, Marconi Radio Officers serving on board P&O ships were given the opportunity to transfer to P&O.

IMC = The Marconi International Marine Communication Company Limited

ss Chusan, Radio Officer 1960s

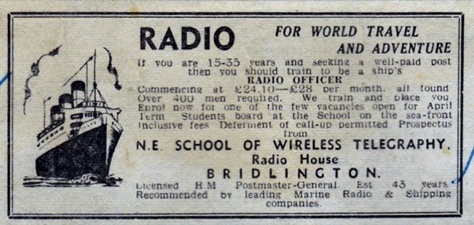

"Short training period, low fees" - so went the advertisement for Colwyn Bay Wireless College in Practical Wireless, Radio Constructor and Wireless World in the 1950s. "See the world on full pay" was another. The glossy brochure for the Glasgow Wireless College at Charing Cross showed a young lad with wavy gold braid on his sleeve reaching up to tune the Marconi 'Oceanspan' transmitter. With his hand on the key the caption read, 'With the world at his fingertips a Marconi Marine Radio Officer prepares to send a message'.

All very enticing for a young man hankering to see the world without having to

'climb the rigging' or 'swab decks'!

The main source of emergency assistance in the oceans has always been the nearest deep-sea ship to your own. Radio Officers kept watch on the international distress frequency in order to render assistance to ships in trouble. When their own ship was in distress, they stayed at the morse key until assistance was at hand - and not infrequently went down with their ship

The Radio Officer not only operated the radio equipment, but also repaired and maintained it. The companies that built and supplied the electronic equipment, and in many cases supplied the skilled Radio Officers to the shipping companies, also had their own technical staff based at various seaports.

During the golden age of maritime communications the globe was populated with hundreds of coast stations, each with its own area of coverage, call sign and personality. Many Radio Officers will remember tuning across the marine bands and hearing these stations, standing shoulder to shoulder with hardly any space between them, calling out for traffic or working ships.

Cape Cod began as Marconi station CC established in 1903 in South Wellfleet. The famous four legged Marconi towers were a primary feature of the station. In the 1930s they were known as Marion Radio, operating on 117kc, 129kc, 141kc, 143kc (later 147kc) 406kc and 500kc as well as twelve frequencies in the HF bands. The site of the original station has almost completely disappeared into the Atlantic due to erosion.

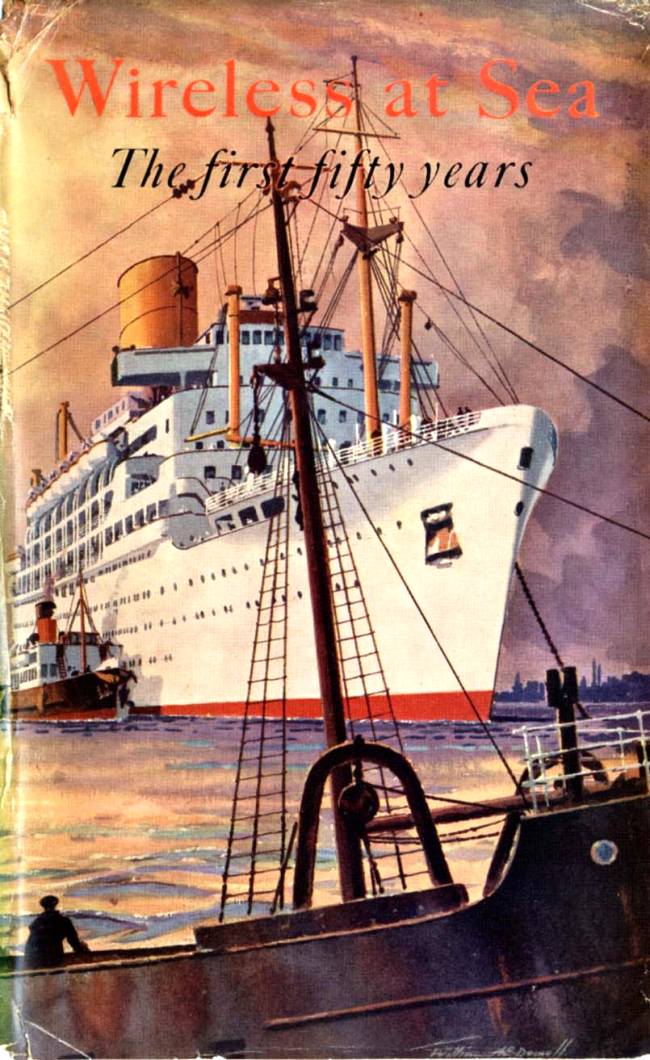

A history of marine wireless communication, published by the Marconi International Marine Company Ltd, to mark their silver jubilee. A wonderfully informative book with an outstanding collection of images. There are 80 illustrations, mostly photographs.

Stories and pictures about the British Merchant Marine seen through the eyes of Radio Officer Alan Patterson. His diaries take us from 1938 through to the end of the war. Alan and his crew managed to escape submarine wolf packs several times. On one especially dangerous run near India, he discovered that the fine bunch of courageous men from the ship he had just left had been blown to bits while returning to India on a British India vessel loaded with munitions.